Transition Zone turf such as Bermudagrass or bentgrass is difficult to keep healthy, and whether there’s cool- or warm-season turf on the course, a good deal of the year’s weather will be stressful. That’s especially true in a year like 2018 with a hot weather showing up almost a full month early and intermittent dips back into cold temperatures.

As the weather changes, it’s important for superintendents to watch for turf pathogens to slow down or prevent diseases before they become an issue. Here are a few to keep an eye out for:

Fairy ring

Fairy ring is one of the easiest turfgrass diseases to diagnose, with rings that span from about 4 inches in diameter to several feet, says Dr. Derek Settle, Bayer Green Solutions Team specialist. There are three types to look out for, with Type 1 showing up as dead brown rings, with the turf killed in the rings. Type 2 is a green ring, which would be the predominant version seen during an early warmup, and Type 3 involves visible mushrooms and puffballs.

“Sometimes you’ll have all three symptoms going at once, but that’s what you’ll look for,” Settle says.

Courses are in danger once soil temperatures reach about 55 to 60 degrees at a 2-inch depth, Settle says. Once those temperatures are covered, superintendents should start off with a cross program fungicide program to prevent fairy ring.

When working with fairy ring, it’s important to remember to water fungicide in to the depth of the mycelium, which is generally going to be in the upper inch of the thatch layer, Settle says.

Working in a preventive action is easier for superintendents, because curative rates can be much higher, Settle says. For example, Bayer’s Prostar’s preventive rate is 2.2 ounces per 1,000 square feet, whereas the curative rate is about 4.5 ounces for the same range. “Curatively, you’re going to have to use it at a high rate, and typically you’re going to have to address it with a second application in 30 days,” he says. “Once the fungus gets going, it’s like a freight train. It’s hard to stop.”

_fmt.png)

Dollar spot

Dollar spot is one of the more significant diseases to watch out for in Transition Zone turf in his region, says David McCall, a turf pathologist at Virginia Tech. “Dollar spot is always king in the Transition Zone, because so many applications are needed throughout the growing season,” he says.

Dollar spot shows up in silver-dollar-sized lesions on the turf, with a bleached or light color. It can be very unsightly, but if it doesn’t kill all the way down to the ground, rescue applications can be sufficient to control the disease and slow it down for a little while, McCall says.

Cultural practices play a tremendous part in handling dollar spot, with the right amount of fertilization, rolling and irrigation, he says. “There are several strategies you can use to minimize the amount of disease you see, and probably the biggest one is managing how you use your nitrogen,” he adds.

Use nitrogen when turf is a little lean, with small amounts over a longer time period. McCall recommends going with a program of about .1 to .2 pounds of nitrogen every 10 to 14 days. “You’ll still need fungicide, but you’ll reduce the overall amount of dollar spot,” he says. “It all starts with cultural practices, that is definitely number one.”

Fungicide options for dollar spot come from multiple classes. DMI fungicides like propiconazole are a strong choice, but have confirmed cases of building resistance, McCall says. SDHI fungicides are also commonly used, though some resistance has been recorded with SDHIs like fluxapyroxad and boscalid in studies at the University of Massachusetts.

To reduce the likelihood of resistance in dollar spot, switch modes of action throughout applications. “You want to rotate with different single-site modes of action, or with multi-sites like chlorothalonil or fluazinam,” McCall says.

Fusarium patch/Pink snow mold

With grass greening up earlier than expected, pink snow mold and fusarium patch, both caused by Microdochium nivale, can be an issue for Transition Zone turf, in the Mid-Atlantic regions, says Brian Aynardi, PBI-Gordon’s Northeast Research Scientist. The disease can be present from above-freezing temperatures to about 60 degrees, but usually in the mid-40s in rainy weather that doesn’t have time to dry when the ground isn’t frozen.

“Anytime you have freezing/thawing cycles is where you’ll see it,” Aynardi says.

Pink snow mold patches will be circular, from 3 to 6 inches in diameter, and will appear pink under sunny conditions, or straw-colored.

DMIs are a good choice for control, as are combination products that contain DMIs with strobilurins or anything containing chlorothalonil, Aynardi says. “Keep an eye out in March and into April, when things start to green and warm up,” he adds.

Pythium root rot

Anytime the soil is wet for a prolonged time period, Pythium root rot can be a threat to Transition Zone turf. “Unfortunately, it is very difficult to identify before you start to see symptoms, so it’d be difficult to do any preventive diagnostic sampling if you don’t know exactly where to pull from,” McCall says.

Once symptoms appear, they’ll often show up in patches in low-lying areas and the areas of the course that stay wet the longest, he says. “You might see the disease track down through waterways,” he adds.

Pythium is a disease that often shows up more during warmer months like July and August, where there’s also heat associated with thunderstorms or overirrigation, but they can show up in spring or fall when conditions reach about 70 to 80 degrees with increased moisture, McCall says.

“If you can understand where your problem areas are with drainage and the areas that stay wet the longest, one thing you can do is focus on site-specific management and try to alleviate some of those problems,” he says.

Symptoms can be orange or yellow patches and can show up in irregular patches and patterns.

If Pythium is suspected anywhere on the course, take samples as soon as symptoms develop and send them off to a diagnostic lab, McCall says. “Because this disease is so destructive, if you suspect you have it, you want to get that confirmation, but it may not be a bad idea to go ahead and make an application while you’re working with a diagnostician to determine if it is the cause,” he says.

Working with an application of something like Segway will be the best option, though there are also other chemistries available on the market, McCall says. There isn’t any known resistance, but the possibility always exists that some could develop given the single-site mode of action and the broad genetic diversity of Pythium.

One issue with Pythium is that it isn’t a true fungus, and most fungicides shouldn’t be expected to cover them the way they do other fungi, McCall says. “You need a plan for Pythium root rot as well as Pythium blight. You should have a plan for your putting greens,” he adds. “Pay attention to your weather forecast, and if it’s going to be hot and wet for a prolonged period, you need to have some kind of protection.”

Leaf spot

The first reports of leaf spot for this year are starting to come in, and they’re about a month early, Settle says. The disease, which shows only on Bermudagrass, has initial infection centers with a purple coloration, always occurring on the stressed areas of the green. On a green, look toward the outer ring on the cleanup lap where the mower causes a lot of wear and stress to the turf.

“The main note I would make is that we sometimes tell superintendents to get a sample to a lab, because it’s the lookalike for Pythium blight,” Settle says. “It’s another example where the human eye is very, very good, but you always want to get a sample and send it to a university to double-check.”

The best approach for leaf spot is a broad-spectrum fungicide, like Interface Stressgard, with two active ingredients, Settle says.

Leaf spot is one of the most chronic diseases for Bermudagrass, popping up in shoulder seasons when temperatures are cool and the grass is not growing vigorously, Settle says. “By the time we get to late spring or summer, you’ll never hear mention of leaf spot,” he says. “By that point, environmental conditions have changed, and the fungus is no longer in the sweet spot for its growth and development.”

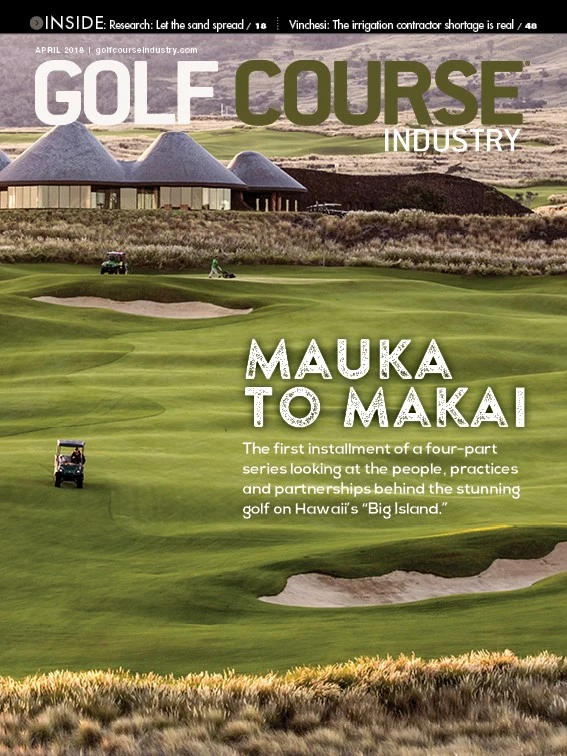

Explore the April 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show