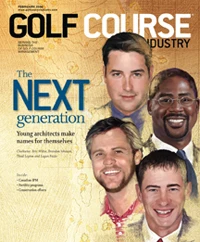

Names such as Fazio, Doak, Nicklaus and Palmer are instantly recognizable in golf course design. But what about Wiltse, Johnson and Layton – or Logan Fazio, for that matter. Not so much. These might be the next big names in golf course design sooner than you think.

Golf course architecture is an interesting profession that requires an artistic side, practical side and the ability to deal with people, says Erik Larsen, executive v.p. of Arnold Palmer Design Co.

“You’re a problem solver and need to gather people together,” he says. “You need people skills to deal with different groups along the way. Designers do their own thing, and architects solve problems. You have to be able to work with and in different projects and styles.”

Larsen refers to three young projects architects at Arnold Palmer Design who will be influential in golf course architecture: Eric Wiltse, Brandon Johnson and Thad Layton. All three are working to become members of the American Society of Golf Course Architects.

“They have more knowledge about what’s happened in golf course architecture with different styles and looks than anybody I’ve seen,” Larsen says. “They have more experience than I did at that time in my career. They don’t let the look of a golf course carry them away.”

Wiltse, Johnson and Layton are students of architecture.

“Their passion has driven their education to learn more about each aspect of the golf course,” Larsen says. “It makes them more exciting and reliable. They pay attention to how good a course can look and how fun it can be.”

The three architects have the ability to look at the competition and see what’s exciting, Larsen says.

“For example, the competition has a style Brandon and Thad wanted to learn about, so they went to play those courses,” he says. “They take the time to look at other things and build an encyclopedia of knowledge. The passion is there. The industry hasn’t seen their new work yet, but it’s going to be something different from us. They will be known guys.”

The orchestrator

Wiltse, who has worked at Arnold Palmer Design for more than 15 years, started right out of high school.

“I lived across the street from Harrison Minchew, who worked for Palmer Design, and when I was 18 or 19 years old, I talked to him about golf course architecture. I learned to draw and draft, and they kept me around. I used mylar, pen and ink to help make topo maps.”

Wiltse, who doesn’t have a landscape architecture degree, learned his craft from Minchew, Vicki Martz, the late Ed Seay and Larsen.

“If I left Palmer Design for school, I would have lost my position,” he says. “From Vicki, Harrison and Erik, I learned more technical experience about drawing and graphic standards and how the company did plans. Ed was more conceptual, and taught how the game is played and how courses played. Ed let me problem-solve in the field. He wanted to see how I could tackle and solve problems. Ed would throw you to the wolves but bring you back in. Ed let people go at their own pace. He had so much experience. If you really couldn’t solve a problem, he’d help you out in need.”

Wiltse worked as a CAD technician when drafting became electronic and soon became the IT guy (he’s the in-house computer whiz), then project coordinator and finally project architect.

“Eric’s mentality is more like ‘let’s get the job done,’” Larsen says. “He’s more of an orchestrator and less about the artistic side than Brandon and Thad. They complement each other. Eric just finished a golf course on the Gulf Coast of Texas that’s true links-like golf. It wasn’t an easy deal. It took Eric a lot of working with different people.”

Wiltse has always wanted to work for Arnold Palmer Design.

“I never entertained the idea of working for anyone else,” he says. “I saw no good reason to pick up and do golf course design for someone else. I figured I was at the best place, so why go anywhere else?”

Wiltse adheres to the design standards Arnold Palmer set, which don’t include target golf, but courses that blend in with their natural environments – more of a traditionalist style.

“Pine Valley is one of my favorites,” he says. “It’s not neat and tidy and wall-to-wall green. I would hope we can get people to understand brown is OK. I don’t think we’ll see the European look for at least another 10 years. Developers want to see lush green. But we’re selling less wall-to-wall green. We’re promoting smaller green sizes because greens have gotten to be huge and have made golf courses less intimate. Golf courses’ environmental impact should be smaller.”

Wiltse likes to design courses where golfers have several options and shots. He’s also keeping an eye on the competition.

“I’m watching what other design groups are doing because it helps me keep sharp,” he says. “I watch tournaments on TV and where the Tour is playing. I visit Web sites to see where other designers are working.”

Since Wiltse has been at Arnold Palmer Design, he has worked on 100 courses, 30 as a project coordinator and three which he designed. He needs two more golf course designs or four renovations to be eligible for ASGCA membership.

“I’ve been a bit laid back about getting into the ASGCA but would like to be in in two years,” he says. “Being an ASGCA member lends credibility to me and the firm. It’s a win-win for me and Arnold Palmer Design.”

Some of Wiltse’s more memorable projects include Star Pass in Tucson, Ariz., where he was the lead architect for the first time; The Bridges Golf Club at Hollywood Casino in Bay Saint Louis, Miss.; The Oasis Golf Club in Mesquite, Nev., where he learned the details of what Palmer likes; and the TPC Boston where he was a project coordinator.

“I’m grateful and honored to work at Palmer Design, and hopefully, I’ve done enough good work to stick around,” he says.

The student

Before coming to Palmer Design in 2006, Johnson gained experience with the PGA Tour and The First Tee.

“I met Brandon years ago and was impressed with him, and when we had an opening, I went out and got him,” Larsen says.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in landscape architect from N.C. State University and a master’s degree in landscape architecture from Harvard University, Johnson started with the PGA Tour Design Services, completing two internships in 1995 and 1997.

“The graduate program is an investment that grows over time,” he says. “It was great to be pushed by those who were in the field. I traveled a lot and worked on large projects in Italy and England that weren’t related to golf. There were diverse projects that made you think about a lot of different things at once.”

When doing the second internship at the PGA Tour, Johnson met Layton, and they became buddies and kept in touch. Johnson also knew Wiltse because they went to the same church. Through those relationships, Johnson met Minchew and Larsen.

Johnson was hired to be an architect at The First Tee and worked there from 1999 to 2006.

“I was to service all chapters and review all sites no matter if it was new construction or a renovation,” he says. “I did oodles and oodles and oodles of plans.”

The biggest difference between The First Tee and Palmer Design is the pieces of land Johnson had to work with.

“With the not-so-choice pieces of land for The First Tee, I was trying to fit in components such as gas lines, power lines and dealing with rock outcroppings and existing roads – things you couldn’t move to build the course,” he says. “At Palmer, you get to work with choice pieces of property, and your decision is different. For example, you’re maximizing frontage next to lakes. At The First Tee, we were forced to be creative with no money. I’m freed up here at Palmer. It was dirt and grass at the First Tee – that’s all we could afford. You learned restraint and what’s interesting on site. At Palmer, we’re working with clients who have the means do it right.”

Even with his experience, Johnson says there was a learning curve working at Palmer Design, and there still is.

“As a designer, you’re always are trying to push the envelope and reinvent the wheel even though we don’t need to,” he says. “We’re always looking for something different. As a company, we’re moving forward, but after 300 courses, it’s difficult to think outside the box.”

Johnson likes traveling and learning about golf courses to improve and remain inspired.

“We’ve built up a pretty good photo file,” he says. “We went to Scotland and played 36 holes a day and took tons of photos.”

Learning what projects to accept was another growth opportunity for Johnson.

“When I first started, we were on site with a client, and Erik Larsen asked me if this was something we should do,” he says. “It was comforting to have a say about the type of client, budget and project and how it might perform. You don’t want to take work that doesn’t fit your mode of operation.

“In the ’80s and ’90s, there were a lot of projects with houses right on both sides of the fairways and a lot of road crossings,” he adds. “This is an example of something we might pass on. We’re trying to work better to think through the land plans. Projects are case-by-case situations. Clients are more sophisticated and savvy. More developers want to do high-quality work and not just jam homes in near the golf course. Better master-planned communities are being more environmentally sensitive and are creating a community with a sense of place.”

Two of Johnson’s memorable projects were the bunker renovations at the PGA National Resort and Seven Falls Golf and River Club in Etowah, N.C.

“We’re able to walk the property and find the routing right there,” he says. “It turned out the way we envisioned.”

Johnson would like to work on a project that’s on a choice site near the ocean with sandy soils and have a client willing to go the extra mile to create something special and give him the opportunities to do what he wants.

“As an architect, I want to be remembered as one who has done great work where people have come from far away to play a golf course I’ve designed,” he says. “I want to create something that people don’t get bored with, that people want to play again and again. I also want to design tournament golf courses to test golfers’ abilities. The trick is to design courses for the best players in the world and for the 20 handicappers.”

Less is more

While visiting his mother in Las Vegas years ago, Layton drove by a golf course that was part of a gated community and never forgot it.

“The waterfall, the beautiful green grass, the light sand bunkers – that image hooked me,” he says.

Layton did research, talked to architects and figured out he needed a landscape architecture degree to pursue the profession. While in junior college, he worked as a laborer during the construction of The Bridges Golf Club where he met Wiltse and Minchew.

“I tagged along with Harrison and Eric and connected with Eric,” he says. “He invited me to the office, and I drove 500 miles to see it. There, I met Erik Larsen and connected with him. From that point on, I always kept in contact with Erik.”

Layton transferred from junior college to Mississippi State University to earn his landscape architecture degree. While at MSU, he worked on the construction of a mom-and-pop course and completed several internships at Palmer Design.

“I kept calling and calling,” he says. “Any time I wasn’t in school, I went to Ponte Vedra (where Palmer Design used to be located) to work.”

After graduating, Layton went to work for Palmer Design full time. Once there, he worked on many different projects, visited many great sites and was exposed to many different styles. He learned from Ray Wiltse, Eric’s father, and Greg Stang, who both influenced him the most.

“They took the time to explain the thoughts behind the design and gave me some of the design to do,” he says. “I blossomed under their direction.”

Layton’s style has evolved from moving a lot of dirt and creating a lot of splashy features in an effort to wow golfers to seeing more value in strategic design and doing away with things that aren’t essential.

“I’m starting to believe in the ‘less is more’ philosophy more,” he says. “Most of our clients can pay for whatever we can draw, so sometimes it’s hard to have that restraint.”

Like Johnson, Layton likes to get out and see other architects’ work as much as possible. He likes the work of Tom Doak and Coore and Crenshaw in particular, as well as Alister MacKenzie and George Thomas.

“I combine others’ styles and throw in my own flair,” he says. “I keep an open mind. I’m an empty cup and work to get better every day.”

Palmer Design is gravitating toward core golf, although new courses are still tied to development, but in a different way, where homes and road crossings aren’t so close to or part of the course. Layton adds that more sophisticated home owners don’t want to be right on top of a course but next to natural areas and lakes.

“If you do golf right, the rest will take care of itself,” he says. “With core golf, you’ll keep natural corridors for animals to go in and out.”

Even though Layton has just one project under his belt in which he was the lead architect (Zhailjan Golf Resort in Kazakhstan) there are several other projects in which he’s the lead architect that are on hold because of economic conditions and other snags.

“It’s frustrating,” he says.

The young Fazio

It looks like the future of Fazio Golf Course Designers will remain in the family, thanks to Tom’s oldest son, Logan, 30.

Logan’s interest in golf course design started when he was 15 and began working on projects with his dad. In high school, he studied mechanical engineering and liked to draw plans.

“Logan wanted to learn from the ground up, like me with my uncle, George Fazio,” says Tom Fazio. “I sent him to work in the Arizona office. He worked in the field and under designer Dennis Wise.”

It wasn’t an issue when Logan came to work for his dad directly, says Tom Fazio.

“Those projects out West (Bighorn Golf Club in Palm Desert, Calif., for example) tend to be the biggest, most multifaceted projects,” he says. “It’s a Ph.D. crash course in golf course management, construction and design.

“I was always the youngest person in the room because my uncle gave me an opportunity at a young age,” he adds. “Logan is in the same boat, but he can handle that because of his personality.”

Logan worked on a few other courses out West before heading east. Then his dad put him in the fire with Donald Trump at Trump National Golf Club in Bedminster, N.J. Logan, a senior design associate, has worked all over the country on many different projects and is now handling projects in the Caribbean. He has experience that ranges from working for contractors to running crews to all details of construction programs.

As far as style, Tom Fazio gives designers freedom.

“We don’t fit any one style,” he says. “All our projects are different and unique. It starts with attitude and personality.”

And Logan has the ability to deal with all different people, Tom Fazio says.

“He can build a bunker, jump in a ditch to put pipe together, work with engineers and go to a meeting to explain projects,” Tom Fazio says. “He’s a people person. You can be a good designer, but you need all the above and need to be a great salesman.”

Tom Fazio says Logan is much more into the details than he was at that age.

“I tend to say get it done,” he says. “Logan gets into the details with the engineers. I wasn’t as sophisticated when I was his age.”

Tom Fazio says there’s no reason for his son to go elsewhere and that Logan wants to take over the company, but Tom Fazio isn’t ready to give up the reigns just yet.

“We work on a lot of projects together,” he says. “I’m involved in all projects. It’s happening more and more where he wants to do more projects than I want to. He has the gift to convince me to do more projects than I want to. Logan has the total package. If I had anybody in the world to make a decision about a golf course or troubleshoot, he would be the guy I’d go to.” GCI

Explore the February 2008 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show