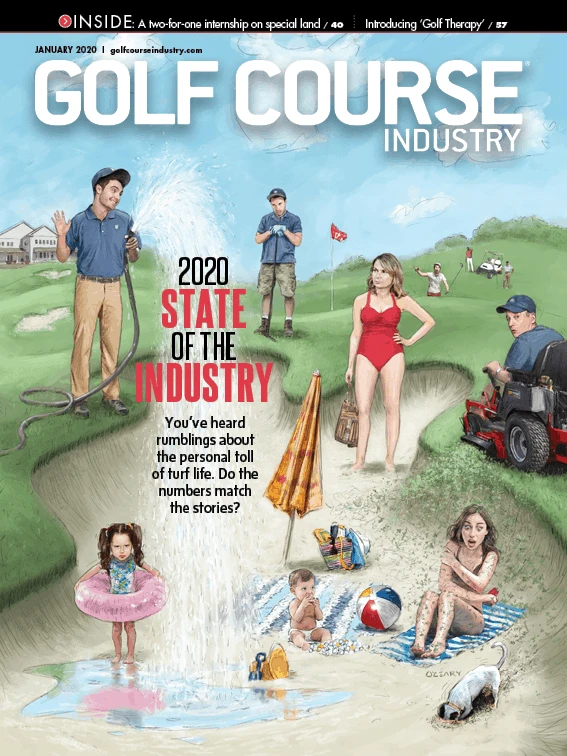

All the charts and numbers in this section tell one story — of an industry on the mend, of operations budgets increasing every year, of hours out on the course dropping just a little and hours back at home filling that gap. Of quality of life improving bit by bit.

But the words on this page and the five that follow tell another story.

Yes, those operations budgets are up again — the mean is more than 16.7 percent greater across the board than last year and almost 41.7 percent greater than five years ago — but even with that figure far surpassing the 8.9 percent five-year inflation rate, it just feels like there is less and less money for ever-more-demanding owners and members.

Yes, the general consensus is that superintendents, directors of agronomy and other turfheads are working fewer hours than in years and decades past, taking more time for themselves and their families, but the course still looms at all hours. There is no escape from nature’s Sisyphean cycle. The course will still call. You will still miss key moments in life.

And yes, despite so much great conversation around the industry especially this last year about mental health, so much work remains. Depression and stress and other disorders are real. Burnout is a part of the job. There are more physically and mentally demanding professions, sure, but that does not negate the toll so many feel between the tees and the maintenance building.

What is the State of the Industry — the anecdotal and micro-state of the industry, far beyond the facts and figures, down to the individual — as we turn the calendar to a new year and a new decade?

For years, Doug Palm allowed his job to define him. And why not? When you have so much fun on the job, even when you work 10-, 12-, 14-hour days every day all spring and summer and early fall, you might as well.

Palm is in his 28th year as the superintendent at Cattails Golf Club, a course with a meager budget in the western suburbs of Detroit. The club purchased a second course earlier this year, nearby Hilltop, which spread his already thin staff even thinner. “At Hilltop, I don’t have a full-timer, and at Cattails we have two full-timers,” he says. “It’s good budget-wise, but it’s tough to get part-timers to always come in.” Because of the course acquisition, Palm worked 89 straight days last year, averaging far more than 70 hours per week, and he took less than a week’s worth of vacation. “You may have guessed I’m kind of a workaholic,” he says.

Even in a region filled with workaholics — among the almost 600 State of the Industry respondents, folks in the Midwest reported averaging 57 hours per week, with 52.1 percent averaging 55 or more and the average longest stretch without a day running more than five weeks — Palm stands out. But his new course demanded it.

“It had been neglected and it was short-staffed to start with,” he says. “I was just involved a lot with working on the property — and learning the property, too. I had to learn the irrigation system, I had to learn the drainage patterns, just all of it. And we had one of the wettest springs we’ve ever had and there were days it was hard to even mow a golf course.”

The new superintendent back on the original Cattails course, where he worked for so many years, provided Palm with plenty of help and might have provided a longer-term solution.

“He did a great job jumping in as a first-time superintendent, so I’m not going to have to spend as much time there,” Palm says. And who is this first-timer who’s saving Palm so much time? “Luke,” Palm says. “He’s, uh, actually my son, Luke Palm. He grew up on that golf course, but he’s really just started to get into the turf business the last few years. He had a head start, but he really doesn’t have any formal turf education yet, just course work and lots of seminars.”

Doug is 60, Luke is 27, and the younger Palm “likes everything about the industry, except for ‘working the way my father works,’” Palm says. “His wife’s a teacher and he wants to take some weekends off. Wants to spend some time with her during the summer.”

The Palms managed a quick trip to North Carolina not long before Thanksgiving, a reward at the end of a long year. It was a golf trip, of course. Did you expect anything else? They played 36 holes every day.

Chuck Ermisch learned as much as he could last year about a new course, too, but as Doug Palm was doing so while also managing an old course, Ermisch was doing so while just learning as much as he could about being a superintendent.

Ermisch is the new superintendent at Painted Hills Golf Course in Kansas City, Kansas, one of almost two dozen owned and operated by Great Life Golf, for whom Ermisch has worked for about four years. For decades, he had worked as a landscape architect who specialized in golf course architecture — his portfolio includes more than 50 projects — “but business dried up and I decided I loved the industry too much. I wanted to learn a little more on the agronomic end, so I jumped right in.”

Ermisch, who recently turned 50, reached out to a nearby superintendent, explaining that he was “no spring chicken anymore” and he needed “to make more than $10 an hour.” His experience landed him an assistant position filled with 12-hour days. Before long, he earned his applicator’s license, learning about management and agronomy.

Great Life Golf moved him to Painted Hills early last year. “It had not had an active superintendent for two months,” Ermisch says, “and was in a bit of a downward spiral.”

He studied the course, studied his membership — plenty of 50-and-older men who love league play, not so many younger long drivers who play from the back tees — and embarked on a trio of impact projects: reestablishing intentionally overgrown bunkers to provide a visual change, improving higher-trafficked areas on the cart paths, and cleaning up tree limbs to allow more light and improve turf quality.

“I kind of approach it by setting realistic goals,” Ermisch says. “Like now that I know what I’m getting into, I’m setting very realistic goals. I know I can get this done. I’m not going to start something and then have it sit there for three years. My only other key for success is time management. I have so many hours per week. What can I accomplish?”

That would require hiring “a really, really reliable assistant,” which is a top goal for 2020 and will allow Ermisch to step back a bit after a packed rookie year.

“You get so tied to the property that you feel everything is on your shoulders. You go home and you’re like, Golly, I wanted to get this, this and this done today and I didn’t do it, and you kind of beat yourself up.”

Ermisch talked with some veterans, including Mel Waldron III, superintendent at Horton Smith Golf Course in Springfield, Missouri.

“I said, ‘I’m just getting started. I don’t want to burn myself out.’

“‘You just have to know when to go home,’” Ermisch says Waldron told him. ‘The golf course will always be there. You have to be the guy who sets the tone.’

“Next year, I would like to get to a position where I work 55 to 60 hours a week, doing the work and also teaching and training and having guys underneath me who want to learn. That’s where I want to go. That’s what I want to do.”

John Gurke is similar in age to Chuck Ermisch — less than a decade older at 57 — but the veteran superintendent is on the other end of his career. On the brink of his 30th anniversary at Aurora Country Club in the western suburbs of Chicagoland, Gurke still carries out chainsaws to cut trees down, then cut them up. The difference from 1990, or 2000, or even 2010, is that, “now I might ask someone else to haul the branches,” Gurke says. “Back then, I was hauling the branches and running them through the chipper, too.”

Gurke is a Chicagoland native who has lived and worked almost all of his life in about an hour’s radius, depending on traffic. He knows his superintendent neighbors and will share equipment and sometimes crew if needed. He still writes a column for the local chapter magazine.

He also tries to limit the hours his crew spends on the course — and the hours he spends in his office.

“What we do, and this has been pretty standard for a long time here, is Monday eight hours, Tuesday seven, Wednesday six, Thursday eight, Friday seven. Then we split the crew on the weekends for three hours and my crew will have a 39-hour workweek. We do pay overtime, but we don’t have a lot. I try to keep those same hours. I’m here doing administrative work before everybody gets here and after everybody leaves. But I’ve never understood a superintendent who tells you he works 80 hours a week. I don’t think you need to. I think somebody who is doing that is misappropriating his time and not using it as efficiently as he should. I can still work seven days a week and they add up to 40 hours.”

The institutional knowledge of working almost three full decades at the same club helps, as does the presence of a veteran assistant superintendent, Virgil Range, now in his second stint at Aurora County Club. “That’s probably my No. 1 reason for still being here and doing this job at my place in life,” Gurke says. “When I do take a vacation or I have to be away for whatever reason, to know he’s there, that’s money. I can’t even tell you how big a thing that is. That’s partially how I’ve evolved to where I am. … Having a seasoned assistant who’s basically already been a superintendent, that’s just a luxury that I can’t imagine being without.”

On the other side of the state, near the Mississippi River, Alex Stuedemann has a larger staff, a larger budget and a higher profile, all expected when you work as the director of golf course maintenance operations at TPC Deere Run and keep the course perfect for the PGA Tour’s annual John Deere Classic.

He also has a similar approach to hours and balance.

“Even for our hourly staff, what we’ve done is we’ll work four nine-hour days Monday through Thursday and then a four-hour Friday, to kind of give them that two-and-a-half day weekend,” Stuedemann says. “I’ll usually take that Friday off. At the end of the year, I’ll try to use up some vacation days, I’ll take a week off and stop in the office to make sure the guys don’t need anything, then go back home and work around the house. You kind of make up for the time you give in July and August.”

Stuedemann is the proud father of two young daughters, one of whom recently started Girl Scouts. Guess who jumped at the opportunity to become a troop leader?

“I can plan a bunker renovation, I can dredge a pond, I can figure out a struggling green, but pulling together a lesson plan and entertainment for five 5-year-olds is quite challenging, I’m learning,” Stuedemann says. “She’s so excited about it, so there’s that added pressure. I was never a Boy Scout — I was a part of something similar when I was younger — but I did recognize that it was something that would give my daughters some perspective on real-life lessons and also empower them. The cookies are part of what they do, but they learn responsibility, decision-making, communicating. If it allows me to spend time with my daughters and see them grow as human beings, I’m all for it.”

Tim Campbell lives in a different state and a different time zone, and works for a smaller course, but just like Alex Stuedemann, he understands the importance of a hobby off the course.

Three years ago, right around the time Campbell turned 50, his father suffered a heart attack that sparked everybody in the family to examine what they were doing on this mortal coil. “My parents told me, ‘You used to do all this athletic stuff. Why aren’t you doing it anymore?’ So Campbell, a 25-year industry veteran who has worked the last decade and a half as superintendent at Palm Beach Par 3 Golf Course, on the Atlantic Ocean, dived right back into the water … and hit the ground running … and hopped on his bike, fitting triathlons into everyday life.

Campbell and his crew end work at 3 most afternoons, “so I’ll usually ride after work three or four days a week, or on the weekends, and then I go to Masters swimming two or three days a week and I make the time to run.” Less than 12 percent of survey respondents said they devote more than five hours per week — less than 43 minutes per day — to fitness. For Campbell, “it was just about making it a priority. Though it does help that I’m single and my kids are all grown.

“I’m sore all the time and I do most of my running on a treadmill, which gets so old,” Campbell adds. “I have a bone spur in my right ankle, behind my Achilles, and I have a boot I wear sometimes at night, but if I’m running and stretching regularly, it doesn’t bother me as much.”

Still, the last three years of training have helped Campbell get rid of stress and become a sharper superintendent and manager — sharper even just in everyday life.

“Most of my other jobs have been six, seven days a week,” he says. “I think part of that is working for the town, too. I’m closer to 40 hours right now than I am to 54, and most of that is because I have a good staff, from my assistant and mechanic to my operators. We have all the tools we need.”

Rory Van Poucke sees more sun even than Tim Campbell, thanks to living in Arizona and working as superintendent at Apache Sun Golf Club, a nine-hole course outside Phoenix. Van Poucke owned and operated courses for decades with his father, Cliff, starting in Illinois in the 1970s before heading west in 1992. He owned Apache Sun until 2005 and is the lone full-time staffer today.

“For me, being an owner, when I owned it and was writing the checks, when your grass goes south and you get Pythium or root rot and you lose the greens, it’s a lot of pressure,” he says. “You have to come up with payroll, your name is on the bottom line and if you go bankrupt, you’re the one who goes under with it. That’s a lot of pressure. Running it for someone, there’s pressure there, too.”

There is pressure on everybody in and around Phoenix, of course, an incredibly competitive golf market where water is fast becoming the focal pressure point. By this time in his career, though, Van Poucke has tried to scale back. He has become more involved in the water conversation locally and nationally, and he closes the course a couple months each summer.

“I’m a little older too, but if I have to work 14 days or 21 days, I work 14 or 21 days because that’s the nature of the beast,” Van Poucke says. “If we have a disease problem, or when we’re seeding, I may work 12-hour days, or go out at 2:30 and check the sprinkler system. That I don’t have a problem with.

“I think there is a lot of pressure on superintendents because there’s just not a lot of room for error anymore. I just try to balance it out along the way and not be married to the job too much. I make sure to take vacations, spend time with my family, maybe take an afternoon off and go play golf with my friends. If you keep looking at the same thing every day, you get stale. You get stressed. You need a break. Communicate, don’t bottle it up. Be transparent and upfront with people. It makes a big difference.”

Ryan Cummings communicated and it has made a difference.

Just last month, Cummings published his essay It’s OK to Seek Help — about how leaning on Tom Zimmerman as a friend and a mentor helped him find strength and stay in the industry — in the pages of Golf Course Industry.

“I still have a lot of bad days out here,” says Cummings, superintendent at Elcona Country Club, just south of Interstate 90 in north-central Indiana. “But I try to find the little positives in each day and take some time for myself just to decompress before the start of the day and at the end of the day. I simplified my days, if that makes sense. I’ve tried not to take everything so serious.”

Cummings still works long hours and long stretches — his peak run was 95 straight days while struggling to find folks who could work Sunday mornings — but he takes far more in stride than he did even just a year or two ago. “I wouldn’t say my work-life balance is perfect — there are things that need worked on for sure — but I think just getting out there are listening to other people tell their stories has helped,” he says. “And it’s not a stigma anymore. It’s OK to have these conversations, as difficult as they are. It’s good to get them out into the open.

“We talk about a lot of things — what’s going on out on the golf course, agronomic issues — but it’s OK to talk about our struggles, too. That’s something I’m always going to continue to work on, is better work-life balance, to make this an industry I want to work in for the next 20, 25 years until I retire someday.”

Cummings is 41 now, the father of two children, a 7-year-old daughter and a 10-year-old son. They come out some Sunday afternoons to learn the game, all together on the course.

“My daughter, she gets about three holes and she’s had enough,” Cummings says. “My son will make it all the way through now. I think they don’t care what we’re doing as long as we’re doing something together.

“My son has expressed some interest in working with me. I wouldn’t discourage him from doing it, I would just make sure he has all the information to make a good decision for his future. Right now, it’s just being with Dad.”

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the January 2020 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Beyond the Page 65: New faces on the back page

- From the publisher’s pen: New? No way!

- Indiana course upgrades range with synthetic ‘bunkers’

- Monterey Peninsula CC Shore Course renovation almost finished

- KemperSports and Touchstone Golf announce partnership

- PBI-Gordon Company hires marketing manager Jared Hoyle

- Mountain Sky Guest Ranch announces bunker enhancement project

- GCSAA names Joshua Tapp director of environmental programs