Soil samples provide invaluable information when determining turfgrass issues. But what’s the right way to harvest and how can a superintendent make sense of the data once it’s delivered?

While the time of year samples are taken isn’t extremely important, timing does remain a factor, says Dr. Eric Miltner, CCA, agronomist at Koch Turf & Ornamental. “Many turf managers target spring and fall, when weather is milder and things may be less busy,” he says. “It does not necessarily make a difference from a soil chemistry standpoint, but it is best to give yourself enough time to interpret results and make decisions regarding your fertilizer purchases.”

As for the physical act of testing, samples should be collected to the approximate depth of the root zone. “A general guideline is 4 inches for greens, and 6 inches for other turf,” Miltner says. “Check with your lab as they may have other recommendations. Either way, let the lab know the depth of your samples. Collect multiple cores to represent the area (eight to 10 per green or tee complex, more for fairways, depending on size). Remove the thatch and mix the cores before subsampling to send to the lab.”

Sample greens individually, on an annual basis, especially if they are sand-based. “Fairways or other areas with ‘native’ soils can be sampled less frequently to stretch your resources,” Miltner says. “You could sample six fairways per year, allowing you to have each fairway sampled on a three-year rotation. Known trouble areas may need to be sampled separately or more frequently.”

Take soil samples from the top four inches of the soil profile, which is where most turfgrass roots exist, says Dr. Travis Shaddox, assistant professor at the University of Florida/IFAS Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center. “Randomly take samples from the location of interest and separate the locations logically, such as No. 1 green, No. 6 fairway, etc.,” he says. “Do not mix soil from healthy turf with soil from unhealthy turf.”

Because the “elements of interest do not change too much over a year,” Shaddox says sampling time can be done prior to the start of the season. That said, he also suggests allowing sufficient time so that superintendents can adjust their purchasing decision according to the needs of the test. This is probably one to two months prior to placing an order, he says.

As a superintendent, Bill Brown, CGCS, always sampled the majority of his property in the fall, typically before any fall fertility was applied.

“I didn’t want to have a ‘false’ look at what my soils were doing,” says Brown, AQUA-AID’s director of brand development. “Throughout the year, if things looked a little off and common solutions weren’t working, I would pull either soil samples or samples for paste extracts to help put the pieces of the puzzle together.”

As a superintendent, he would use a standard soil probe that would pull about a ¾-inch plug.

“I would mark the probe with either duct tape or electrical tape to ensure I was pulling the same depth for each sample,” Brown says. “[It’s] important to speak with your laboratory first to understand if they want the top thatch and grass removed. Some want it all in the bag, some want the top removed so you are sampling just the soil.”

Brown doesn’t recommend holding onto any kind of samples. “If I was taking samples, it meant I wanted them right away, needed some answers,” he says, adding he would usually receive results back from his lab within five business days of sending, which he called “pretty standard.”

“Typically, I would take soil samples to understand my level and balance of nutrition in the soil,” he says. “Think of your soil as a savings account. You need to make sure you have enough nutrients banked at both the correct rations and levels. When the turf needs to pull from the soil because foliar feeding isn’t sustainable, you need those nutrients available.“If things weren’t adding up, I would pull a sample to have a paste extract completed,” Brown adds. “This type of test tells me what my levels of nutrients are actually in the plant. I have seen plenty of times where soil samples come back near perfect, but past extracts are way out of balance. You have to understand what your turf is doing.”

Test times – start to finish – can vary considerably. This is largely dependent on the lab, their capacity, and their current work load,” says Dr. Grady L. Miller, NC State University professor and extension turf specialist in the Crop and Soil Sciences Department.

“I know our state lab posts on their website their ‘current sample testing turnaround times.’ They are usually two to three weeks,” he says. “If [in] a low-demand time, they may be quicker, etc. They run more than 300,000 samples a year through their lab so they can get backed up sometimes. There are some labs that have two-day turnaround times for rush services. This is generally a type of service provided by private labs ... and additional fees may apply for their rapid response.”

As for concerns about the time between taking the sample and having it tested, Miltner says the biggest risk of waiting too long is potential contamination of the samples if not stored properly. “If you are doing any kind of testing for biological parameters though, you do need to move more quickly,” he says. “Check with your lab regarding their requirements.”

Soil samples can remain viable for a very long time as long as they have been dried, Shaddox says. “Fresh, moist samples should be sent to the lab as soon as possible to minimize any fermentation, which can alter the analysis,” he says. “Most laboratories can process a sample and return a report in one week. The actual process [is] 24 hours to dry the sample, 30 minutes to extract the elements, and around one hour to analyze the extractant.”

Making Sense of the Tests

The test results are in, but looking at numbers in their raw form alone can be a little daunting. Most soil testing reports have both numbers and diagrams to help the reader understand relative nutrient content in the soil and then translate that to the probable response they would see by adding nutrients as they relate to the current soil content, Miller says.

For Brown, the report was only one tool in his arsenal for growing healthy turf.

“Often a lab tech would provide some recommendations, but to be honest they only get a small picture and snapshot with my samples,” Brown says. “I would evaluate and create some programs, but also relied heavily on manufacturing and distributor reps for input. They see hundreds of golf courses and facilities a month. They hear what is working and what isn’t. At the end of the day, it was my decision, but I never shied away from anyone offering an opinion.”

Choosing a Fertilizer

Multiple factors determine the recommended fertilizer.

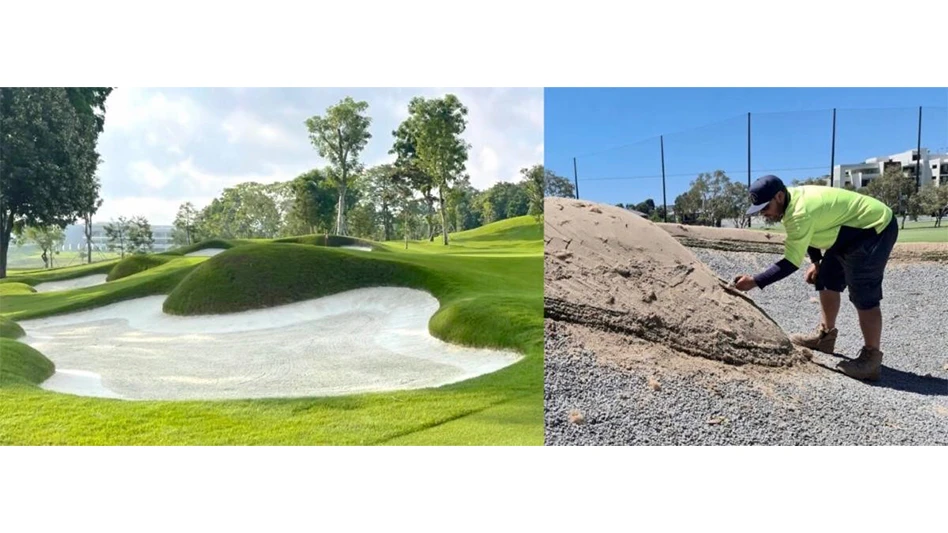

Soil test results are important, and these should inform the balance of nutritional content in your fertilizer, Miltner says. For example, sandier soils make the use of slow- or controlled-release fertilizers more critical (unless you are spoon-feeding), and turf species can have an impact. “The season and weather can also influence your decision on source, nutrient release rate and availability,” Miltner says. “Utilize the 4Rs of Nutrient Stewardship when planning your fertilization program: apply the Right Source, at the Right Rate, at the Right Time, in the Right Place. It is important to balance these factors when choosing your fertilizer.”

Then there’s the decision between organic and inorganic fertilizers There are advantages and disadvantage to both. “Regardless of the source, nutrients are taken up by the plant in inorganic forms,” Miltner says. “Even if you apply organic fertilizers, they need to be converted to inorganic forms first.

“Organic fertilizers may improve soil quality by introducing organic matter (although in relatively minor amounts), and potentially providing food sources for microorganisms. Potential downsides are increased cost due to the low nutrient value and associated need to apply greater amounts of fertilizer. In addition, if you face phosphorus restrictions in your area, use of organic fertilizers may be impacted.”

On the other hand ...

With synthetic fertilizers, there is a potential of putting down more fertilizer than is needed, Miltner warns. However, synthetic fertilizers offer a broader range of options for enhanced efficiency properties (stabilized nitrogen, slow-release, controlled-release), and blends can be customized to meet a turf manager’s specific needs based on soil test results.”

Brown shared advice he received in the past when discussing options. “There certainly are advantages and disadvantages to organic versus synthetic,” he says. “I am comfortable saying you could probably host a weeklong conference on both philosophies and still leave scratching your head. For me it was what was best for my budget, my amount and timing of play. I was more of an organic granular feeder. I felt I got the best bang for my buck and good season-long nutrient bank and release.

“One of my mentors — the great Stan Zontek — used to tell me, ‘Bill, the turf doesn’t know how much you spent on that fertilizer. In the end, nitrogen is nitrogen. Just feed the plant!’ I kept my foliar programs very basic with mostly single nutrient source products so I could keep control. It was also more cost effective with an ever-tightening budget.”

Explore the February 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Toro continues support of National Mayor’s Challenge for Water Conservation

- A different kind of long distance

- Golf Construction Conversations: Stephen Hope

- EnP welcomes new sales manager

- DLF opening centers in Oregon, Ontario

- Buffalo Turbine unveils battery-powered debris blower

- Beyond the Page 66: Keep looking up

- SePRO hires new technical specialist