If you work a night schedule at a course like Stone Mountain Golf Club by Marriott in Stone Mountain, Ga., you have to get used to the coyotes around you. That’s advice from Anthony L. Williams, the retired superintendent who oversaw maintenance of the course from 2005-15. You also have to watch out for deer and other wildlife — like owls. “The first time you get a good fly-by from a big owl, you’re thinking, ‘I may have a stroke and a heart attack all at the same time,’” he says.

Given the right circumstances, heading a crew in the dark is worth it. Prepare the course for early golfers and stay out of their way. Plus, the stigma attached with following the path of the night waterman of lore, who Williams says “perpetuated all the stories that the golf course was haunted” and “didn’t run with the rest of the crew,” dissipates into the atmosphere like evapotranspiration as crews routinely come out in groups. However, night operations can be problematic due to safety concerns, potential hiring and scheduling conflicts, weather factors, and just plain darkness.

A superintendent of Marriott courses for 30 years, Williams began experimenting with night maintenance about 12 years ago at the now-closed Renaissance PineIsle Resort and Golf Club at Lake Lanier Islands, Ga. Then, he implemented it at Stone Mountain. Over the years, Williams and the Stone Mountain crew switched back and forth between night and day schedules at the club’s two 18-hole courses, Stonemont and Lakemont. “Even though we had 36 holes and we could do maintenance gaps and we could close nine or we could flip and start in different rotations, there was an awful lot of times where our business model was, especially in the summertime, everybody wanted those (tee times) from sunrise to 9 a.m.,” he says. “Man, that was our time. And we realized we could get three or four extra times if we were starting earlier, and that was kind of the push.”

Williams and crew performed more night maintenance on Stonemont than Lakemont to avoid crashing equipment into Lakemont’s lakes, but Stonemont has some steep turns and cart paths they had to watch out for. The immediate safety question was how to find the best lighting. At the time, some companies produced mowers with lights; other mowers the crew had to retrofit. With lighting, as with anything else, there are budget questions. Lighting large areas helps with safety, but it also costs more to light large areas than it costs to light smaller areas.

The process of trying to mow a straight line at night versus during the day, Williams says, is met by fewer distractions in one sense, but in another, it involves a different mindset and approach. It takes more time to ensure safety and accuracy while mowing greens, collars, tees and fairways. “So you’ve got to kind of know where you’re at as far as can you get two or three holes ahead and that’s what you can do before the sun comes up, or can you actually do all or most of your maintenance at night?” he says.

Weather affects night maintenance in a number of ways. Rain at night presents a whole slew of problems, including diminished quality of cut and complications mowing slopes. Region also largely influences conditions from course to course. Crews at flat, South Florida or desert courses regularly work full nights to avoid the persistent heat, Williams says. But crews at northern courses with bentgrass greens that are susceptible to frost in the spring and fall, more often limit night schedules to summers. Year-round night maintenance might not work in the Transition Zone, either, where superintendents cover Bermudagrass greens in the winter.

After a while, the crew at Stone Mountain – tending to bentgrass greens – adjusted to the schedule like clockwork. Williams would post a shift for, say, 3 a.m. and they would be there. For some 7:30 a.m. shotgun starts, he would schedule them for a time as early as midnight and they would work all night. “It kind of depends because there are some things you can do kind of a little bit ahead of it,” he says. “You might not be mowing rough at night. But then again it’s an expectation, too. If it’s a high-end client, like a big charity tournament or a member/guest or something, you may be trying to double-cut greens.”

Superintendents at other courses oversee two separate shifts to accomplish goals at night. At the 18-hole Coeur d’Alene Resort Golf Course in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, Kevin Hicks manages two different crews – one that usually works from 5 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. and another that usually works from about 2 p.m. to 10:30 p.m. The course has had some form of night maintenance since it opened in 1991, 12 years before Hicks joined as superintendent.

As daylight changes throughout the golf season – April to the end of October – so does the second crew’s shift, sometimes beginning as early as noon. “We try to play off of that light a little bit,” Hicks says. The light varies significantly throughout the year, too. Located in the Idaho Panhandle, Coeur d’Alene is approximately 90 miles south of the Canadian border and 40 minutes west of the Mountain Time Zone. It isn’t usually until the tail end of the season, though, that the first tee times move to later and the morning shift switches to a 6 a.m. start time.

The Coeur d’Alene Resort Golf Course does things differently than other golf courses. For instance, its 14th green floats on water. Clutter on the course is kept to a minimum, Hicks says, which means no benches on tees, and restrooms are sunk into the ground. The maintenance crew’s first priority is to stay out of the golfers’ vision, with the occasional exception of hand-watering and other nonintrusive maintenance. “My saying with my staff is, ‘We’ve got plenty of time with two crews. If you can see the whites of the golfers’ eyes, you’re way too close,’” Hicks says.

Golfers’ demands to not see maintenance crew on courses, Williams says, has been around as long as the game itself. “Not only do you need great agronomics and the rest of the design features and everything, but you do have that expectation that guys just really want it to be perfect, and they really don’t want to see you making it perfect while their group is playing,” he says.

The morning crew at Coeur d’Alene mows greens, tees and fairways and prepares bunkers (“traditional stuff,” Hicks says), and the evening crew performs trim work and mows roughs. While slightly reducing the quality of cut, the morning maintenance helps eliminate wet feet on the fairways and aids in the total guest experience.

The success of a night maintenance schedule largely hinges on hiring, Hicks says. “The makeup of that staff member that can work into the dark is really different than the early risers,” he adds. “They’re just wired differently. And they don’t cross-train well. You hire with the specific notion that, ‘Yeah, I’m not really a morning person.’ That’s your guy for the night crew.”

Issues sometimes arise at Coeur d’Alene when two crews are on the course at the same time and they have to fight over equipment, Hicks says. Later at night, crew mow five or six mowers wide and sometimes accidentally knock out irrigation heads when they randomly pop up.

Part of the challenge with managing two crews, Hicks says, is just letting things fall into place. “It’s difficult because you want to be here the whole time, but you have to have people that you trust, and I do, and it’s just a matter of me letting go and letting them do what they’re good at,” he says.

In golf course maintenance, the key is to work with a group that is willing to experiment, Williams says. “It’s that willingness, that curiosity, that drive, to say, ‘Well, let’s go see. Then we’ll find out for sure. And if it’s an absolute train wreck, then we won’t do that again. And if it works out and it allows us to be more competitive, then great for us.’”

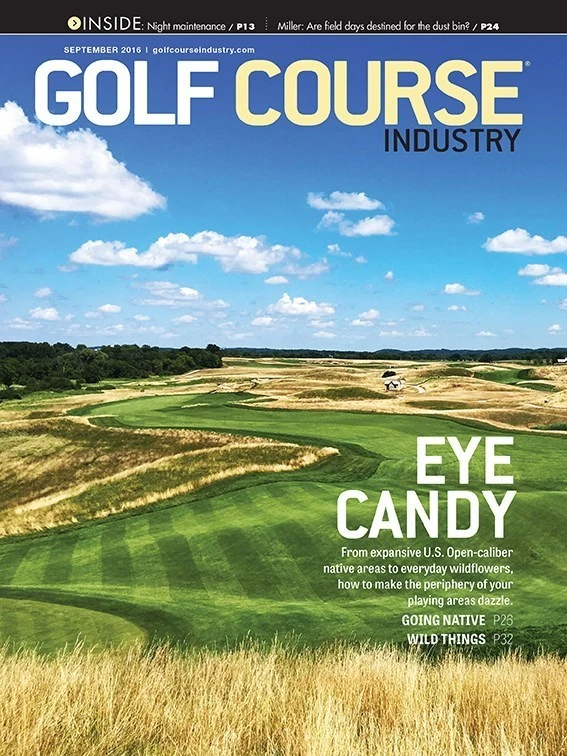

Explore the September 2016 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Editor’s notebook: Green Start Academy 2024

- USGA focuses on inclusion, sustainability in 2024

- Greens with Envy 65: Carolina on our mind

- Five Iron Golf expands into Minnesota

- Global sports group 54 invests in Turfgrass

- Hawaii's Mauna Kea Golf Course announces reopening

- Georgia GCSA honors superintendent of the year

- Reel Turf Techs: Alex Tessman