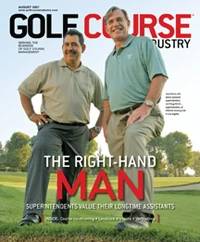

The typical assistant golf course superintendent is a young buck with a turfgrass degree in hand. He’s excited and eager to become a golf course superintendent as quickly as possible. The goal is to move up to the next level in about five years, but these days, it’s not as much of a lock as it used to be.

But there’s another type of assistant superintendent who doesn’t receive as much attention – one who’s just as valuable as the young buck, although in a different way. He’s the longtime – or career – assistant superintendent. He knows the intimate details of the course and crew because he’s been there for a while, as long as 20 years or more in some cases. His job is simple in theory, which is to make life easier for the superintendent.

Follow the leader

Doug Martin, golf course superintendent at the Wilshire Country Club in Los Angeles, has been working with his assistant, Jose Rocha, for 22 years. Martin, who has been a superintendent for 12 years and in the industry for 23, worked for Bruce Williams at the Los Angeles Country Club for 10 years before Wilshire. He came to the L.A. Country Club two years after Rocha arrived there.

“We were both hired on the grounds crew,” Martin says. “I was a foreman working on the South Course, and Jose worked on the North Course. As I got promoted, he followed in my footsteps. As we went along, he kept the same attitude and took personal responsibility for doing a job right.”

Rocha, who is originally from Mexico, worked at the 36-hole LACC for 23 years, starting at the age of 18 in 1982. His father worked on the landscaping crew that took care of the nongolf course areas such as the clubhouse.

“I first started on the landscaping crew, working with flowers, around tennis courts and on lawns,” he says. “I did that for one year. Then, the golf course maintenance crew was short of people. I was interested in spraying pesticides and operating different machines. The landscaping side became boring.”

When Rocha first started on the golf course maintenance crew, he changed cups, operated string trimmers and raked bunkers. Then he progressed to mowing greens and tees. Soon after that, the golf course superintendent at the time, Mike Hathaway, said he saw something in Rocha after seeing him work.

“‘You’re responsible,’ he told me,” Rocha says. “He pulled me aside and said, ‘I need someone to man the crew, to be a foreman.’ I was paired with Doug to work together. Then Doug became superintendent on the North Course.”

Rocha became the foreman on the North Course and then worked for Martin in the capacity of an assistant without the formal title. Under Martin, Rocha eventually earned more responsibilities involving more paperwork and scheduling. He also learned more about irrigation, ultimately seeing the bigger picture of golf course maintenance.

After about 10 years as a superintendent at the LACC, Martin was ready to progress and thought he went as far as he could at the club.

“I wanted more responsibility, and Wilshire was a good fit,” he says. “I had talked to Bruce about the next step. I wasn’t in any rush, so it had to be the perfect job. Bruce kept me informed as opportunities arose. I received a lot of support from Bruce to make the move.”

The transition was smooth for Martin because the LACC and Wilshire are similar: Both are private, are on the West side of L.A., have similar climate and grass, have similar budgets per 18 holes, and even have members who belong to both clubs. However, Wilshire has fewer members (475) than the LACC (1,500).

Martin talked to Rocha about wanting to move on.

“When I heard Doug was moving on, I was happy because I knew he was ready to take that job,” Rocha says. “I felt kind of bad, though, because we had worked closely together for so many years.”

Martin has more responsibilities now compared to when he was at the LACC, including dealing with members more closely. At the LACC, Williams handled the relationships with members and worked closely with the membership and green committee, Martin says. At Wilshire, Martin has the final say with the budget, unlike when he was at the LACC.

But it wasn’t until Martin had the job at Wilshire that he talked to Rocha about coming to work with him after one of the former assistants left.

“Jose stopped by to visit, and I mentioned I was looking for an assistant,” Martin says. “I conducted a nationwide search and interviewed other people, but he was the right fit. He had the right communication skills. He was good at motivating the crew. I talked to Bruce extensively to see if it was OK for Jose to move over here.”

Rocha, who doesn’t have a college degree, says he wasn’t planning to go anywhere before Martin mentioned the Wilshire job.

“I was happy at the L.A. Country Club,” he says. “I knew the guys well. I was with them for 20 years. One day, I went to see how Doug was doing. I was convinced I wasn’t going to get another chance at an assistant’s job. I knew if I was going to stay at the L.A. Country Club, I was going to be a foreman for a long time. I wasn’t moving up anytime soon.”

Like Martin, Rocha has more responsibilities now compared to when he was at the LACC. These involve personnel and planning, as well as learning more technical aspects of the job, such as the intricacies of the irrigation system – programming the computer, learning about heads and nozzles – and which pesticides to apply and when.

“He’s improving on organizing the staff to be as productive as possible, but sometimes I intervene,” Martin says about Rocha. “Jose is also improving on technical aspects of the job. I help him in this area, too. He’s improving on these aspects but isn’t ready to go solo yet.”

Rocha says he has learned a lot from Martin, such as being responsible, understanding pesticide labels, being involved in projects and being more organized.

“Doug also gives me freedom to get ideas together,” he says.

Rocha says he also feels comfortable with the crew, 90 percent of whom are Hispanic, even though he’s only been there a year and a half.

Martin says he feels lucky to have an assistant like Rocha.

“We know how each other thinks and know each other’s strengths and weaknesses,” Martin says. “I can relax when I’m not there.”

That relaxation is tied to Rocha’s confidence.

“When Doug leaves to attend meetings or go on vacation, I run the place without problems,” Rocha says. “I know what he likes. I have a lot of respect for Doug as a person and employer. I have a lot of trust in him. I’m at where I’m at because of Doug.”

Rocha also helps Martin with one of his weaknesses – Spanish.

“Jose speaks better Spanish and has more patience with the staff,” Martin says. “Some communication is better coming from him.”

Martin values Rocha and says it’s ideal to have two types of assistants – the stability of Rocha and the excitement of a young guy.

“The trend in the industry is to hire an educated graduate because of his technical experience,” Martin says. “That creates a different kind of environment. I have another assistant, Mike Prouty, who’s going along the superintendent path. He keeps me on my toes. When a young fellow joins the crew, he’s excited about the job and constantly is learning and asking questions. It’s good to be questioned about what you do and to receive an influx of new ideas. But if these assistants move on, you lose consistency.

“On the other hand, Jose has intimate knowledge of the course and crew,” he adds. “He knows what’s going to happen.”

On the same page

Like Martin and Rocha, Joe McCleary, CGCS, at Saddle Rock Golf Course in Aurora, Colo., and his assistant Richard Hurd, have been working closely together for a while – 11 years to be exact. They’ve been at Saddle Rock together since the course was under construction, which started in 1995. It opened in 1997.

McCleary, who has a four-year horticultural degree from Kansas State University and an MBA from the University of Colorado at Denver, has worked for the city of Aurora for 17 years. Before Saddle Rock, he worked at Meadow Hills Golf Course in Aurora as an irrigation technician. Meadow Hills is where McCleary and Hurd first met 20 years ago as seasonal laborers while McCleary was attending KSU.

Hurd, who’s in his sixth year as assistant superintendent at Saddle Rock, left Meadow Hills after 10 years and went to Saddle Rock for a change of pace.

“I wanted to pursue a different path and experience new construction,” he says.

During the construction of Saddle Rock, when Hurd was reintroduced to McCleary, Hurd’s responsibilities included checking the irrigation system installation and helping with the grow-in. He also worked on projects tying in new grades throughout the property. For example, when the new clubhouse was built,

Hurd tied in road crossings.

“When they rough grade, it’s pretty rough,” he says. “Construction is a challenge, especially when tying everything in. Irrigation was also a challenge. When we established new turf, it remained weak for a while. There was little housing at the time, and the wind sucked the irrigation right out of here. But once we established a good stand of turf, it was nice.

“I wish every college kid could go through the construction process to see how much work is involved,” he adds. “It’s not easy.”

McCleary’s trust of Hurd and Hurd’s responsibilities have grown throughout time.

“During the past seven or eight years, I’ve felt more confident leaving the course,” McCleary says. “Part of that is my maturing.”

After the course was built, a lot of home-building was happening next to the course, and McCleary needed to communicate with the developer often. Since the homes have been completed, McCleary feels more comfortable leaving the course.

“It would have been too much to put Dick in charge of both the course and the relationship with the developer,” he says. “It wasn’t something you could just put on someone’s desk to take care of.”

Hurd’s responsibilities include the daily scheduling of the crew, with whom he has a close relationship, and hiring.

“When I became an assistant, I became in charge of hiring, scheduling and managing the staff,” he says. “I’m a good judge of character. We have good rapport with the seasonal workers. They’re the backbone of the industry. Without them, it would be hard to get stuff done.”

One of the aspects of course maintenance that Hurd isn’t responsible for is the development of the budget.

“I work with Dennis (Lyon, CGCS, manager of golf for the city) on that,” McCleary says. “But I talk about budgeting for labor and equipment with Dick. He and other full-time staff are aware of budget performance.”

McCleary also is responsible for the fertilizer program. There isn’t much disease pressure in Aurora, so that isn’t much of an issue, although McCleary says his eye is trained for spotting disease and treating it, unlike Hurd who would have difficulty with that because he’s colorblind.

The biggest benefit of McCleary working with Hurd for 11 years is Hurd’s experience and knowledge of how important relationships are within the city of Aurora.

“I feel confident that when I leave the course he can run the operation,” McCleary says. “When I’m on vacation, the details are taken care of. The pro shop staff and golfers wouldn’t know the difference if I’m gone. I was off for two weeks in July. I haven’t had a long vacation in 12 years. That shows my confidence in Richard and the staff. And being part of the city’s seven courses, Richard can call on other courses for management help if needed.”

Having a longtime assistant such as Hurd has allowed McCleary to take time away from the course to serve on the board of the local superintendent’s chapter, of which he was past president, national committees for the GCSAA and the Colorado Golf Association.

“I might be gone a couple of days, so having a strong, experienced assistant has allowed me to devote more time to the industry at the volunteer level,” McCleary says. “I’d be hard pressed to find a disadvantage of having a guy like Richard. It’s a huge benefit to have a guy with that much experience. “If I moved on, he could take care of things. He could move up in the future.”

Hurd says he has learned a lot from McCleary. They work well together and complement each other.

“Joe is an avid golfer – I’m not, but I don’t mind playing,” Hurd says. “Joe is a professional and very smart. He’s one of the smartest people I’ve met in life. I might have the attitude like, ‘What does it matter, it’ll be here tomorrow,’ as opposed to Joe’s attitude, which is more like ‘Get it done today.’ I’m more laid back than Joe. I have the seasonal mentality at times.”

Working together with McCleary so long, Hurd knows what McCleary expects, such as smooth, rolling greens and straight, clean edges.

“We expect the same results,” Hurd says. “We know how to address the staff when we see something that isn’t right. We talk to individuals and explain the steps they take to better the project and prevent that mistake again. Joe and I are great communicators. We ask the staff for ideas, such as changing the fairway lines. Our whole attitude is to let them have ownership. We’re not always banging heads and have a great working relationship. The staff self-manages, making my job easier. We’re a tight-knit group and expectations are very high.”

Even though Hurd says he’s happy and isn’t looking for another job, McCleary doesn’t want to get too comfortable assuming he’ll be there forever. He knows Hurd has been working to finish his associate degree amid raising two children.

“Education is important to me, and I encourage it,” McCleary says.

“I’m mostly working on experience,” Hurd says. “I don’t know if I’d go to another course. If there’s an opportunity to better myself, I’d consider it. Joe and I will look to better ourselves. If we’re together for another 20 years, great, another five years, great. But as for right now, we have a good thing going. This is one of the best jobs you can ask for, and few people have this opportunity.”

A good teacher

Perhaps the superintendent and assistant who have worked together the longest are Paul Voykin, golf course superintendent at Briarwood Country Club in Deerfield, Ill., and his assistant Moe Sanchez. Voykin has been working at Briarwood for 46 years, Sanchez for 43 years. One of the reasons for staying so long at one club is how members treat them.

“I like the people here very much, and they have been very good to me,” Voykin says. “They have taken pride in what I do. I’m a purist. I don’t look after the pool or the tennis courts – just the 18-hole golf course. I’ve always worked with a green chairman. I’ve made good relationships and formed an ‘ecology’ here for years. I have an excellent friendship with the village.”

Sanchez was a teenager when he started at Briarwood, following his father, who worked for Voykin for 44 years.

“My dad started with Paul in 1962,” Sanchez says. “Then I came up from Mexico and started in 1964 at the age of 15. “Paul raised me like his own son. I started reading books when I was younger. I never went to school in the states. Paul taught me English. I owe everything I know to Paul. The most important things Paul taught me was that everything has to be neat, to be observant, organized and retain a ‘spring fever’ attitude throughout the season. He taught me to be persistent and not let a job go to the next day and stay on top of things.”

Sanchez started out raking bunkers and mowing greens for three or four years. Then he became a mechanic.

“I was given the opportunity because the old one died,” he says. “I was a mechanic for a while then Paul asked me to help him on the golf course. He started teaching me everything about it.”

“I’ve never had a better friend, and nobody has a better assistant,” Voykin says about Sanchez. “He thinks like I do when it comes to the golf course. Moe is right there by my side. I don’t have to tell him to be there when there’s a crisis.”

Voykin, who will retire in a year and a half, will recommend Sanchez for the superintendent job when he retires, even though Sanchez has no college degree and only some high school education. Yet Sanchez passes a tough Illinois pesticide test every year to receive a state applicators license, Voykin says.

“Members love Moe,” he says. “The problem is the demand for communication and appearing in front of committees. That’s difficult for those who aren’t used to it.”

Voykin says the club has assured him he will have a generous retirement package when he retires. In the meantime, Voykin doesn’t worry about Sanchez leaving Briarwood, as he would with a younger, college-educated assistant.

“Some superintendents have gotten awards for having 100 assistants move on to become superintendents in the field,” he says. “That’s admirable, but you have to start over every time they leave. Then you might get a better assistant or a worse one.”

Even though Voykin works seven days a week, he doesn’t come in first thing in the morning anymore because Sanchez takes care of the crew.

“For 44 years, I got up at 4:30 and went to work,” he says. “It’s such a relief to have Moe start the men off. When I get here, everything is humming and buzzing. When you have a guy like Moe, you can take real advantage of him and go on vacations or have him working seven days a week, but I never do. I have a great crew. My men do all the work, and I get all the credit.” GCI

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the August 2007 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Carolinas GCSA raises nearly $300,000 for research

- Advanced Turf Solutions’ Scott Lund expands role

- South Carolina’s Tidewater Golf Club completes renovation project

- SePRO to host webinar on plant growth regulators

- Turfco introduces riding applicator

- From the publisher’s pen: The golf guilt trip

- Bob Farren lands Carolinas GCSA highest honor

- Architect Brian Curley breaks ground on new First Tee venue