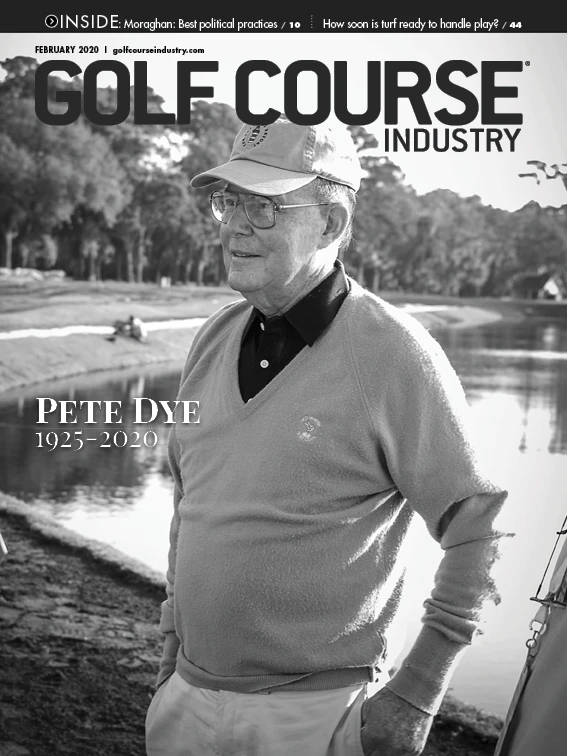

Golf lost its greatest living example of ingenuity Jan. 9, 2020.

Pete Dye designed – and motivated people to build – courses on swamps, coal mines and air bases. He never officially moved mountains or oceans, but his designs hugged stunning landforms from the California desert to the Dominican Republic coast.

His creations transformed sleepy places such as Hilton Head Island, South Carolina; Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida; and Kohler, Wisconsin, into global destinations. Private jets and meetings with billionaires filled the back nine of his life. None of the glitz flustered Dye. Born Dec. 29, 1925, in Urbana, Ohio, a quaint town west of Columbus, Dye remained loyal to his Midwest roots. Developers sold seven-figure homes around his work; hourly employees saw their lives change because of the sacrifices they made fulfilling his vision.

A day with Dye offered glimpses of old and new ways of designing and building golf courses. Dye ordered gigantic machines to move millions of cubic yards of dirt, yet his hands represented his most valuable construction tool. He outlasted younger, stronger workers on job sites. He always had another feature to examine, hole to inspect and site to improve.

“There’s an overriding factor among the guys who truly worked with Pete. They are damn hard-working guys. For Pete to share with you, he had to respect you.” – Allan MacCurrach

He served in the Army during World War II, although he never made it overseas. Harry Truman ended the war less than a year after Dye reported to Fort Bragg to learn how to jump out of airplanes. Fort Bragg is 42 miles from Pinehurst, where Donald Ross lived. A Scot born in 1872, Ross died in 1948. Dye played and maintained the Ross-designed course on Fort Bragg with his Army superiors and Ross watching.

After selling insurance in his wife Alice’s hometown of Indianapolis, Dye combined a passion for golf with business acumen to achieve what others struggled to accomplish in the decades immediately following World War II. Dye honored Ross and other Golden Age Goliaths using a style that modernized course design.

“He invented a golf architecture which did not shy away from showing the influence of the human hand,” says Tim Liddy, a talented architect who worked with Dye the past three decades. “The contrast of the hard fairway lines, fairway edges, bunker edges and green edges built golf courses of clarity. They are powerful, dramatic.”

Dye’s tactics satisfied demanding clients and golfers with evolving tastes. Crooked Stick opened in 1965 and hosted the 1991 PGA Championship. The Ocean Course at Kiawah Island opened in 1991 and will host the 2021 PGA Championship. The courses are as dissimilar as two of his favorite foods: apples and turkey sandwiches.

For all the complexities in his work, Dye remained a simple person shaped by a childhood spent outdoors. Like readers of this magazine, he worked on a golf course as a teenager, watering greens at Urbana Country Club, the nine-hole course where his father was a member. The club made a 16-year-old Dye responsible for its playing surfaces when the superintendent got drafted. “Somehow or another, I was able to kill all the greens,” Dye joked in his 2008 World Golf Hall of Fame acceptance speech.

A collection of superintendents, shapers, builders and associates attended the induction ceremony. These were Dye’s people. His name will forever be attached to Harbour Town, TPC Sawgrass, Whistling Straits and dozens of other innovative courses. Dye’s people will tell you golfers who enjoy those courses will never fully understand his legacy.

ALLAN MACCURRACH HAS never completed his third week of work. Following a fight with his father, the PGA Tour’s first agronomist, a defiant MacCurrach wanted a job on the crew building TPC Sawgrass. He was just 14 in 1979. “I said to my dad, ‘Give me a job out there building that golf course,’” MacCurrach says. “He said, ‘You won’t last two weeks.’”

MacCurrach started his career by picking up sticks. He was then handed a rake and told to work contours on the third green. On a sweltering summer day, a middle-aged man approached MacCurrach and two co-workers. The man circled the green, inspecting contours with an eye-level tool. The man wanted subtle slopes, not the smooth and slick surfaces the trio produced. The man jumped on a bulldozer and destroyed their work. MacCurrach gave his father an earful about the “crazy gardener” who ruined the third green. “That was my first introduction to Pete,” MacCurrach recalls more than 40 years later. “My dad told me to quickly shut up and do whatever the gardener tells you to do.”

Dye completed TPC Sawgrass in 1980. He then started building The Honors Course outside Chattanooga, Tennessee, and MacCurrach spent the summer of 1981 living with Dye and construction crew colleagues in the maintenance facility. MacCurrach graduated high school the following summer. One day after the ceremony, he drove from Jacksonville to Denver to help Dye build TPC Plum Creek. MacCurrach obtained a two-year degree in turfgrass from the University of Massachusetts and, in 1987, founded MacCurrach Golf Construction. The company’s portfolio includes more than 20 Dye-designed courses.

“There’s an overriding factor among the guys who truly worked with Pete,” MacCurrach says. “They are damn hard-working guys. For Pete to share with you, he had to respect you.”

Dye and Alice, who died last year, shared plenty with MacCurrach during the latter stages of their respective lives. MacCurrach frequently shuttled the pair from airports to projects, always stopping at Dairy Queen to satisfy Alice’s ice cream cravings. MacCurrach ate cheeseburgers and watched the final round of the 2015 PLAYERS Championship in a Florida hotel room with the duo. Eventual champion Rickie Fowler went eagle-birdie-birdie on the heralded TPC Sawgrass closing stretch to enter a playoff with Sergio Garcia and Kevin Kisner.

“When the tournament ended, Pete’s phone started ringing off the hook,” MacCurrach says. “Everybody wanted Pete to say something after somebody brought the ‘evil man’s’ golf course to its knees. He was cheering for Rickie like everybody else.”

“Guys like me are going to do the best to carry on that torch and we’re proud of what we learned from him. It’s a tall order. You can’t replace a guy like that. He was one in a million … one in 10 million.” – Chris Lutzke

That crazy, evil gardener who MacCurrach met at the course where Fowler earned his biggest victory sure had a way with people.

“Those guys who had the opportunity to work with the man will forever remember it,” MacCurrach says. “There were a lot of guys inspired by Pete. I guess the marketplace would call them ‘small guys.’ They aren’t in Golf Digest today and they won’t be tomorrow. But he shaped their careers, because they showed up to work at one place and met this guy named Pete Dye. And the next thing they knew, they were doing something pretty cool.”

Or something they could be proud of whenever their father called. “Up to the point my dad died, he would call me and ask, ‘How are you doing?’ MacCurrach says. “I would always say, ‘Just going on that third week there.’”

DAVID STONE ANSWERED a call from the pro shop after guiding the Holston Hills crew through a morning shift in June 1982. P.B. Dye, one of Pete’s two sons, and two other members of The Honors Course construction team planned to play golf later in the day and they needed a fourth. Stone agreed to lead the trio around Holston Hills, an excellent Donald Ross design in Knoxville. After the round, P.B. and his colleagues drove the hundred miles back to The Honors Course, and Stone returned to the business of leading a team through the Tennessee summer.

Then, in September, Stone received another call. This one wasn’t filtered through the pro shop. P.B. wanted Stone to visit The Honors Course to discuss the possibility of becoming the club’s superintendent. “I was pretty happy with where I was at,” Stone says. “I said, ‘I don’t know how interested I am, but I’d love to meet your dad.’”

Stone did more talking than Dye in their first encounter. Dye proved uber-curious around agronomists. By the end of the conversation, The Honors Course had its new superintendent. Stone and Dye remained close friends following the opening of the course, with Dye frequently making pro bono visits to the club. Dye’s grand vision inspired Stone. In the late stages of his 35-year run at The Honors Course, Stone convinced club leaders to move a road to clear room for a spacious practice range. “Pete taught me you can’t be afraid to change something,” Stone says.

Stone taught Dye as much about agronomy as perhaps anybody. Stone’s turfgrass knowledge resulted in The Honors Course becoming the first Dye-designed course with zoysiagrass fairways. The periphery includes a variety of aesthetically pleasing and wildlife-promoting native grasses recommended by Stone. Dye praises Stone in “Bury Me in a Pot Bunker,” a candid account of the architect’s career and work co-authored with Mark Shaw. “David is probably the best thing that ever happened to The Honors,” Dye writes.

The book was released in 1995. Stone reflected on the unsolicited compliment shortly after Dye’s death. “I wasn’t aware the book was being written until it came out,” Stone says.

Now retired, Stone is working with a few members on a club history. Dye is a huge part of the club’s story.

“You read about how your life can be changed by a few people or one particular situation,” Stone says. “If PB and those two guys hadn’t come up and played golf with me, it might have never happened. I just loved Pete’s work and his courses.”

SUPERINTENDENTS WERE OFTEN Dye’s point person at a club. This proved especially true at The Golf Club, an early Dye design in New Albany, Ohio, where Keith Kresina has worked and studied Dye’s early work for more than 30 years. Kresina met Dye as an assistant superintendent in 1990. Five years later, Kresina had become the club’s superintendent, so he frequently got the call … Pete Dye is visiting. He wants to meet with you.

“Whenever he came on property, the superintendent had to be there,” Kresina says. “He wanted to talk to the superintendent. He wouldn’t step foot on the property when the superintendent wasn’t there.”

The pair would meet at the pro shop and walk the course – Dye shunned carts even in the final years of his life – mostly in silence. Agronomy questions often broke the silence. Dye leveraged the expertise of superintendents to elevate his work. “He wanted to know about agronomy,” Kresina says. “He wanted to know how to grow stuff in the shade, how the greens were performing.”

Opened in 1967, The Golf Club is one of Dye’s earliest designs and it melds Scottish flair (railroad ties) with enduring playability concepts (trouble left for low handicappers and room right for high handicappers). Neither its tasteful features nor decades of rave reviews mattered to Dye in a memorable exchange with Kresina during a quiet walk.

“I asked him, ‘What do you see?’” Kresina says. “His answer was, ‘Mistakes.’ I thought that was an interesting response. He was looking at all the mistakes he made early in his career as a golf course architect. He wanted to make sure he was improving.”

Dye waited until his late 80s to receive the mulligan he wanted. He completed a major renovation at The Golf Club, just 63 miles from Urbana, in 2014. “I feel very fortunate to be in the right place at the right time,” Kresina says. “It was the chance of a lifetime to work hand in hand with him on a project.”

LESS THAN 30 miles from the Atlantic Ocean, on north Georgia land once owned by Henry Ford, Dye completed another major renovation in 2014. He ate soup – along with two scrambled eggs, two pieces of toast with jam, bacon and sausage – every morning he visited The Ford Plantation.

A big breakfast was needed. Dye looped The Ford Plantation course twice daily on his visits. An entourage accompanied Dye in the morning. Dye, who had a hearty appetite, would stop at the clubhouse and grab a turkey sandwich and more soup for lunch. Once sunset approached, the group typically consisted of just four people: Liddy, lead agronomist Nelson Caron, green committee chairman Dr. Bill Thompson and a MacCurrach Golf Construction representative. “It was totally sunup to sundown,” Caron says. “At the end of those days, you were totally mentally exhausted. He required you to be on top of your game.”

Sacrificing for Dye yielded major rewards. Caron first met Dye in 2003 while working as an assistant superintendent at the River Course at Kingsmill Resort. Stone then hired Caron as an assistant at The Honors Course, which brought back Dye to rebuild a pair of holes in the mid-2000s. When the head turf job at The Ford Plantation opened, Caron approached Dye about calling director of golf CW Canfield on his behalf. It took Dye multiple tries to get through, because Canfield didn’t believe the caller was actually Dye.

“He called back two minutes later and said, ‘This is P-E-T-E … D-Y-E. Don’t hang up on me!’” Caron says. “Then, of course, CW didn’t hang up on him and they had a big laugh. I still had to come through and perform the interview, but that was quite the endorsement from Mr. Dye. Without him, I wouldn’t be sitting in the chair that I’m sitting in today.”

The renovation allowed Caron to establish a personal relationship with Dye, who was more than twice his age. As the entourage discussed construction specifics, Dye frequently pulled Caron aside. The private chats left indelible impressions.

“All he wanted to hear about were my twin girls,” says Caron, who created The Pete Dye Scholarship Foundation for young professionals with interest in golf course maintenance. “I thought about that for years. At the end of that 14-month stretch working with him, he knew everything about me personally and he didn’t forget anything, either. Maybe one of the reasons he was so accomplished was that he got people like me to totally buy into what he was selling. It would be hard to not follow Pete. He was just that great of a leader.”

David Swift met Dye when he was 21. He served as the host superintendent for a major championship contested on a Dye-designed course at 27. He spent large chunks of his time at Whistling Straits trying to keep pace with the indefatigable architect.

“It was a love affair,” says Swift, the current superintendent at Minnehaha Country Club in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. “You had to love what you were doing, because it was all day and all night. That’s how we got things done. Looking back, it’s like, ‘Holy cow! Look at what we did!’”

Swift worked for the Kohler Company from 1999 to 2009. In preparation for the 2004 PGA Championship, Dye executed several alterations to the Straits Course, which opened in 1998. Dye visited Kohler weekly during the shoulder seasons and winter, leaving the crew with what Swift jokingly called “two weeks’ worth of work” to be completed before his next visit.

“He was never done,” Swift says. “You would be in the dirt with him, laying on your chest, looking at a bunker. And the next minute you’re standing on the hood of a truck looking at something out in the distance. It was constant and you were looking at the world through a whole different set of eyes. I never knew that attention to a detail. I was just a grass guy.”

Swift estimates his Minnehaha crew spends a third of its time executing long-range projects. Angles. Tweaks. Open-minded dialogue. “When I’m training my team, I feel like there’s a part of Dye in me,” he says.

Saeed Assadzandi is on his third general manager position, this one at Bethesda Country Club, a private facility bordering the Capital Beltway. Before wading through club finances and politics, he received a double dose of Dye.

“When I’m training my team, I feel like there’s a part of Dye in me.” – David Swift

Assadzandi led the agronomic efforts during the construction of Mystic Rock at Nemacolin Woodlands in southwestern Pennsylvania. His first interaction with Dye included a brief conversation about the work schedule. “He said, ‘So, you’re going to work on a Pete Dye golf course? I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ He said, ‘Are you ready to work on the Pete clock? I said, ‘Yes, sir. What’s that?’ Sunup to sundown, seven days a week.”

When Mystic Rock opened in 1995, Assadzandi continued working at Nemacolin Woodlands as the director of golf, grounds and ski operations. Dye contacted Assadzandi in 1997 about assisting with a “little project” in Wisconsin on a former Army base with a runway through the middle of the property. “You don’t tell Pete Dye no,” Assadzandi says.

Assadzandi saw the results of hard work at Mystic Rock. He saw a humble genius operate at Whistling Straits. Wearing sneakers, khaki pants rolled up to his ankles, small jackets with different logos and a baseball or flat cap, Dye directed the movement of 800,000 cubic yards of dirt and sand to build the Straits Course. Dye didn’t work off plans, although Assadzandi sometimes noticed sketches from various courses under Dye’s cap bill. Dirt sketches are part of Dye lore, so Assadzandi carried a camera to remember what the architect wanted. Besides wearing the same clothes, Dye ate salmon cakes nearly every day for lunch at Whistling Straits.

“When it came to designing a golf course, you couldn’t find a more unpredictable person,” Assadzandi says. “When it came to his daily routines, he was very predictable.”

Assadzandi left Whistling Straits in 1999 to become the general manager at Champion Hills Golf Club, a course nestled within an upscale western North Carolina community. “I wouldn’t be sitting in this chair if it wasn’t for the lessons learned from him,” says Assadzandi, who moved from The Country Club of North Carolina to Bethesda Country Club in 2018. “Those were seven of the best years of my career working under his direction.”

A 2 a.m. phone call rarely ends well.

Dye wanted a stubborn coal magnate named James D. LaRosa to contact industry veteran Gary Grandstaff about becoming the superintendent at a course he was trying to build on an abandoned mine in Bridgeport, West Virginia. LaRosa picked an odd time to call Grandstaff, who was in his second year as the superintendent at Valley Country Club in suburban Denver.

The call placed Grandstaff in the middle of two strong personalities involved in a project with seemingly no end. LaRosa commenced construction in 1979. The Pete Dye Golf Club officially opened 16 years later as the only course bearing Dye’s first and last name. LaRosa hired Grandstaff on April 15, 1989 to work alongside Dye.

“He told James D. LaRosa, ‘This was one of the best courses I have ever designed, so why don’t you finish it?’” Grandstaff says. “They argued about finishing it all the time.”

Dye never viewed any course as 100 percent finished. But the Pete Dye Golf Club had to open at some point, because, “you eventually run out of money,” Grandstaff says. “We ran out of money, but we just kept spending James D.’s money.”

LaRosa’s money, Dye’s creativity and Grandstaff’s agronomic tact produced 18 distinct holes atop reclaimed land. Dye incorporated elements of the land’s previous life into the design, using smokestacks as aiming points on the fifth hole and a mine shaft to connect the sixth green and seventh tee. His most wonderful West Virginia feat might have been handling LaRosa. Dye calls LaRosa “the toughest, most tenacious, never-give-up son of gun I’ve ever worked for” in “Bury Me in a Pot Bunker.”

Watching Dye navigate LaRosa emphasized the importance of patience to Grandstaff, an Ohio native who wandered between projects and courses before landing in West Virginia. Grandstaff first met Dye and his brother, Roy, while touring Wabeek Country Club outside Detroit in 1970. Grandstaff kept in touch with the Dyes and leveraged the relationship into finding a permanent home.

Grandstaff retired in 2019 after 30 years at the Pete Dye Golf Club. His career proves not all 2 a.m. phone calls end poorly.“Pete gave me a chance when he didn’t have to and he was a good friend,” Grandstaff says. “I talk to a lot of young men in this business and they are all looking for a place to go. They want that break. Pete gave me that break.”

Pete and Alice Dye paid Chris Lutzke’s way through the turfgrass management program at Michigan State. Then they paid his way through the school’s landscape architecture program.

Lutzke joined the construction crew at Blackwolf Run, the first Kohler project involving Dye, as an 18-year-old in 1986. He dug deeper bunkers and mounds than his co-workers. The boss quickly noticed and Dye asked Lutzke if he wanted to spend a winter helping build Old Marsh Golf Club in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida. Old Marsh was less than 30 miles from Pete’s and Alice’s Delray Beach home. Weekdays digging alongside Dye turned into exhilarating weekends.

“I didn’t care to know what day it was – and neither did he,” Lutzke says. “He had tunnel vision. If the sun was shining, he was working, back then and even late in his career. It was a helluva ride.”

Lutzke worked regularly with Dye for more than 30 years. Dye stressed the importance of academic training to his employees. Lutzke applied to the turf program at Lake City (Florida) Community College in 1988. But Dye pointed Lutzke to Dr. Trey Rogers at Michigan State.

Lutzke holds two degrees from Michigan State. He has worked hundreds of 80-hour weeks while helping Dye design more than 20 courses. The American Society of Golf Course Architects elected Lutzke as an associate member in 2018. Pete and Alice Dye, along with Donald Ross, are among the society’s past presidents. Lutzke now owns a golf course architecture firm with Paul Albanese. “I have never worked with Chris Lutzke,” MacCurrach says, “but I know that son of a gun must work hard because Pete had a lot of respect for him.”

Dye’s people ate turkey sandwiches from Subway under trees with him, kept an eye on his Belgian German Shepard “Sixty” and made sure he returned to the room in time to watch “The Andy Griffith Show.” Work hard. Get an intimate glimpse of an incomparable legend.

“Guys like me are going to do the best to carry on that torch and we’re proud of what we learned from him,” Lutzke says. “It’s a tall order. You can’t replace a guy like that. He was one in a million … one in 10 million.”

Explore the February 2020 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Beyond the Page 65: New faces on the back page

- From the publisher’s pen: New? No way!

- Indiana course upgrades range with synthetic ‘bunkers’

- Monterey Peninsula CC Shore Course renovation almost finished

- KemperSports and Touchstone Golf announce partnership

- PBI-Gordon Company hires marketing manager Jared Hoyle

- Mountain Sky Guest Ranch announces bunker enhancement project

- GCSAA names Joshua Tapp director of environmental programs