With the coming of fall, golfers throughout the northern regions begin counting down the days to the end of their golf season. But it is also the time of year when many superintendents are beginning preparations for next season. Their golf courses may soon be empty and/or covered with snow in a matter of weeks. But these dedicated professionals are already envisioning what their facilities will look like when they green up in the spring.

One concern for superintendents is avoiding a disease outbreak at the start of the season when the turf may be vulnerable. Dr. John Kaminski, the director of the Golf Course Turf Management Program at Penn State University, maintains that the most effective way of warding off disease in the spring is to nurture healthy turf through the fall and into the winter.

“I think of it as fundamental Turf 101,” he says. “I think the stronger you are going into winter, the more likely you are to avoid some avoid some (disease issues) that you may come across.”

Dr. Jim Kerns, associate professor and extension specialist of turfgrass pathology at NC State, agrees. “Turf that struggles through the winter months is predisposed to disease in the spring,” he says. “Pathogens are opportunistic, therefore having weak plants at any time can allow for disease development.”

When it comes to heading off early season disease problems, Kaminski says superintendents working in northern sections of the United States and Canada are at a disadvantage. “The northern guys have the challenge of having annual bluegrass,” he says. “You can have perfect turf and still have a bad winter and get turf loss, but the adage of having healthy turf going into the winter is definitely going to be important.”

The primary disease issue confronting northern-based superintendents each spring is snow mold, whether it be pink, gray or speckled. “The type depends on snow cover and conditions in the spring or before snow falls in the winter,” Kerns says. “In order to get gray or speckled snow mold, at least 60 days of snow cover are required. Pink snow mold, or Microdochium patch, does not require snow cover and can be severe when temperatures reach 65 degrees Fahrenheit or below with periods of high humidity.”

Beware of snow mold even before colder weather sets in, Kaminski says. “Pink snow mold can start up in October and become active,” he says. “So, you’re going to have to be on the lookout for that. Gray snow mold … everybody’s putting out preventative applications for that sometime around Thanksgiving or Christmas depending on how far north you are.”

Another concern for superintendents tending to bentgrass greens is take-all patch. “The disease won’t show up until the following summer,” Kaminski says, “but the best time to apply fungicide is when the pathogen is active. And that’s going be in the fall, October and November.”

As an alternative, the fungicide can be applied in the spring but in any case, soil temperatures should be between 55 and 65 degrees, Kerns says.

Other disease issues a superintendent might have to face come spring include, depending on the variety of turfgrass, spring dead spot, large patch, fairy ring or take-all root rot.

In addition to applying fungicide, Kaminski recommends maintaining an ongoing fertility program through the fall as well. “I think what (superintendents) want to do is continue fertilizer programs at a moderate level,” he says, “and as the turf starts growing more as we get into the fall they can bump that up a little bit.

“They key to me is getting a good fertilizer down where the plant is going to store that and not use it all. So, you’re basically going to want to continue to fertilize it as normal and then right before the grass pretty much shuts down but is still able to take up those nutrients. Then it will store (the nutrients) over the winter and give it a better chance of surviving some of the pressures over the winter.”

Fertilizers can be beneficial. Kerns notes potassium’s effectiveness against spring dead spot, but he says fertilizers are not a substitute for fungicides. He says when dealing with issues such as large patch, spring dead spot and take-all root rot, the applications must be scheduled to coincide with a period when the soil reaches a temperature of 70 degrees at a 2-inch depth for a minimum of four or five consecutive days. He says that in these instances the calendar should be set aside. “Pathogens respond to temperature and moisture,” he says, “not the season.”

The weather is the wild card in all this. “The weather has been odd,” Kaminski says. “Everyone says it’s getting so warm but in 2013-14 and 2014-15 we had some of the worst winters that we’ve had. You can’t predict that. And so you have to do the basic things to protect your turf; with fertility and fungicides, and hope that things turn out in the spring.”

Superintendents must be alert to the prospect of having to deal with issues they haven’t faced before. Both Kaminski and Kerns are seeing issues that, while not new, are becoming more common farther north than in years past.

“We’re seeing some oddball diseases,” Kaminski says. “We’re seeing an unusual Pythium that’s hitting Poa. Not in the winter, it’s a seasonal thing. Thatch collapse is a new disease that we’ve seen. There’s really no good control for that; we just try to tell people to treat it like fairy ring.”

Some diseases that in years past were more problematic in the Transition Zone are now advancing northward, Kerns says. “We’ve diagnosed Pythium root dysfunction and Pythium root rot in more northern areas than we have in the past,” he says. “Another disease that seems to be more problematic is summer patch. It also seems like nematodes are more problematic in more northern climates.

“I do not want superintendents reading this and freaking out. These diseases are by no means occurring as frequently as we see them in North Carolina, but the incidences seem to be increasing. (But) this is just an observation and we do not have data to support that claim.”

In the end, Kaminiski says disease control comes down to adhering to the basic principles of turf management. “I think the thing is just try and stick to the fundamentals.” he says, “and don’t get so far removed from doing normal things that you know are going to result in a healthy plant.”

It’s important to not subject the turf to unnecessary stress and increase its susceptibility to disease. “A lot of times we see people whose expectations are so high and are just pushing their turf so hard for such a long period of time that it that makes it a little tough,” Kaminski says.

Some facilities will remain open throughout the winter. Others will close, allowing not only their turf but also their superintendents to reenergize. Winter provides a window for superintendents to attend turfgrass conferences or take other steps to expand their knowledge base, Kaminski says.

“When the winter season hits, it’s conference season,” he says. “There are always new things that are coming out and are important. It would be good for superintendents to go and continue to update themselves on the latest information that’s out there because things are changing fast.

“This new disease with Pythium … a few years ago it was thatch collapse for us. There are a lot of new things that are coming out and there are also new management options like the new nematicides that are out on the market. Kind of educating themselves about it and knowing what to look for. I think it’s a good time, as you get into winter and put the grass to bed, to really focus on revitalizing yourself and that includes continuing education.”

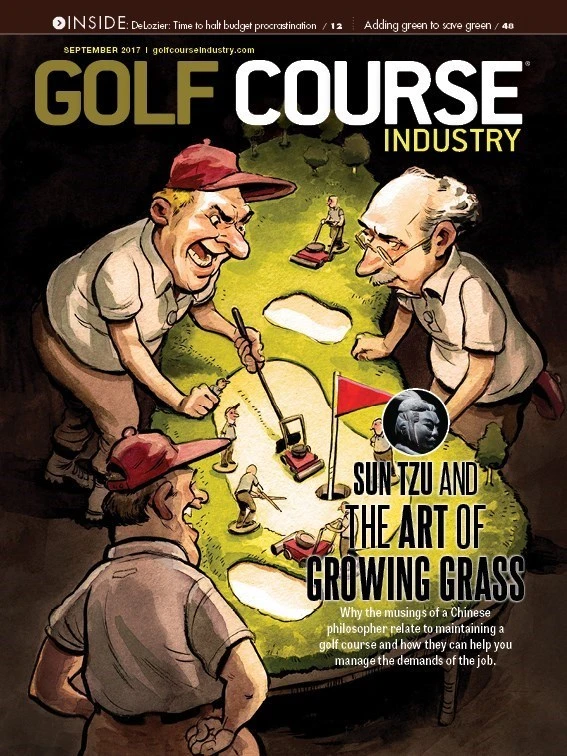

Explore the September 2017 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show