I have spent years (full disclosure: more like decades) having to occasionally tell golfers that the collar is part of the green. This conversation usually comes up when a golfer is spotted pulling — and often parking — his or her pull cart onto the collar. This statement on my part is usually met with a look of either bemusement or confusion.

“Really?” is most often the response I get.

Collars have often seemed, to me at least, the forgotten child. They’ve always taken a backseat to the green itself. Which is, I suppose, somewhat understandable. The green is the crown jewel. The crème de la crème. Let’s be honest: nobody asks about the speed of the collars or how they’re holding shots.

But the collar, as most superintendents can attest, is indeed part of the green surface. Not only visually does the collar provide an appealing edge to the manicured surface of the green, but we manage them much the same as we do the green. Perhaps the biggest difference on the maintenance side — separating the green from the collar — is simply the height of cut.

Although many of us consider collars part of the green, they definitely add unique maintenance challenges and present a few headaches. Collar maintenance, if anything, has become more difficult in recent years. In my opinion, lower cutting heights; increased play producing more traffic and compaction; hotter, drier summers; and superintendents eliminating core removal from their maintenance practices are expanding the collar conundrum. A lesser problem, but an issue for some of my colleagues, involves the original construction of greens complexes not extending outward to the collars, meaning they might have poorer draining subsurface.

I spoke with a few superintendent peers and a USGA Green Section agronomist to get some other takes on modern day collar maintenance.

“It is a problem I see more and more each year,” USGA Green Section Northeast Region agronomist Elliot Dowling says. “And I don’t see the problem going away on its own.” Dowling cites a few interesting observations that I hadn’t considered, including a slightly different perspective on the “traffic” issue. “Collars see a disproportionate amount of traffic” he adds. “Turning greens mowers on them, stopping and starting rollers on them, as well as driving sprayers, topdressers and other pieces of equipment over them, can all weaken the turf further.”

Dowling also thinks the explosion of plant growth regulator usage hurts the health of collars. “One of the most damaging things done to putting green collars is plant growth regulator overspray,” Dowling says. “Superintendents want to make sure the putting green is covered, but they don’t want to waste product on the surrounds, so the booms are often turned off and on over the collar. Consequently, collars are often overregulated, which can lead to problems. When turf stress and thinning occurs, recovery is slow because of that overregulation. Moreover, recovery from traffic or environmental stress is slow as well.”

I also spoke with Country Club of Rochester (New York) superintendent Rick Holfoth about his collar management philosophies. Holfoth agrees with Dowling that turning on the surfaces with the greens mowers is something that must be avoided for the health of the collars. “We mow a short-cut rough pass around the collar,” Holfoth says. “That is where all mower turns are supposed to occur. This has reduced abrasion injury that occurs when turning either a greens walk-mower or triplex.”

Holfoth mentions the benefit of giving the collars additional corings beyond what the greens at Country Club of Rochester receive. “We usually try and give the collars one to two additional aerations each season, which is basically one pass around with the aerifier, plug cleanup and a topdress.” Other tactics Holfoth implements to protect and enhance collars include using wetting agent pellet when hand watering collars exclusively, resodding extremely worn collar areas and managing traffic around the repairs as they grow in.

Collar mowing height is a management technique I have experimented with at our course in western Washington the last couple years. As we reduced greens mowing heights, collar mowing height also had to be adjusted. Keeping the collar height at .350 or even .300 when you are mowing greens at .110 or even .100 can be too severe of a difference. I’ve found that when mowing greens at .110 in-season, I’ve had to lower the collar height to .275. Although this solves the severe height discrepancy, it does make it more challenging to keep collars healthy at the lower cutting height.

Clay Payne, superintendent at Buffalo Dunes Golf Course in Garden City, Kansas, also has experimented with his green vs. collar cutting heights differential. “We are able to keep the greens height right at about .125 in season,” Payne says. “We’ve found that collars cut at .300 work well with this height.”

Payne has discovered that managing collars exactly the same as greens works well for the program at Buffalo Dunes. “We manage our collars as if they were greens,” he adds. “Same soil amendments, fertility, wetting agents and cultural practices. … It is the same variety of bentgrass as our greens. The only difference is the height of cut.”

Preventing the green edge from moving throughout the season is an issue Payne and I both encounter. When mowing a clean-up pass on greens, operators often cut into the collar wherever the collar bends into the green at a curve. They then often perform the opposite when the green turns at the corners. Green shrinkage is a reoccurring problem in corners.

To keep the edge where it’s supposed to be, I paint tiny white dots where greens either shrink or expand. Payne is planning to experiment with another idea this year at Buffalo Dunes.

“We are going to mow collars in front of greens mowers, so the greens mowers know exactly where the edge is based on dew removal,” he says. “Hopefully, this helps with trying to keep the collars and green edges from ‘moving’ in-season.”

Collar mowing frequency is another fascinating topic. I mow collars once a week in spring and fall. The frequency increases to twice a week during the summer.

David Beanblossom, the superintendent at Chariot Run Golf Club in Laconia, Indiana, adheres to a less-is-better approach. “In-season, we only mow collars two days a week,” he says. “I feel the key is getting by with less mowing due to our reduced nitrogen inputs and our use of PGRs. We are also non-aggressive with them as far as groomers and verticutting goes. Our aerification consists of one to two times a year pulling cores, and two to five aerifications throughout the year.”

The biggest collar headache Beanblossom sees is the universal issue of localized dry spots. “We make sure our greens wetting agent spray includes collars,” he says, “and we hand water using wetting agent pellets.”

Dowling provides one more interesting idea based on his observations: the elimination of collars.

“What I see in the region over the last two to three years is eliminating collars and transitioning that area either to putting green or to surround,” he says. “I like to recommend making the area putting green wherever possible, to increase the size of the greens and perhaps add additional hole locations. In some cases, however, it does make more sense to turn the old collar into surround.”

For those of us not quite ready to take that bold step of eliminating our collars, Dowling has some definite guidelines for keeping the surfaces as healthy as possible throughout the season.

“Collars should certainly be on their own maintenance program independent of putting greens or surrounds,” he says. “Try to keep growth regulators off them the best you can. This is made easier if you have GPS sprayer technology. But if not, apply PGRs alone or with another product that it’s OK if the very farthest edges of the greens do not receive the products.”

And what about traffic? “Where possible, turn mowers and sprayers well away from the putting surface and the collar, basically in the surround,” Dowling adds. “Also, alternate where you stop and start rollers. For example, one day stop and start on the green, the next time stopping and starting on the surround. This spreads wear from the roller away from the collar.”

Collars certainly comprise the smallest physical area of critical turf on the golf course, yet somehow these pesky strips of turf seem to present one of the biggest headaches to superintendents each season.

Collar maintenance is always evolving. New ideas, techniques and products can hopefully help prevent collars from becoming the weak link.

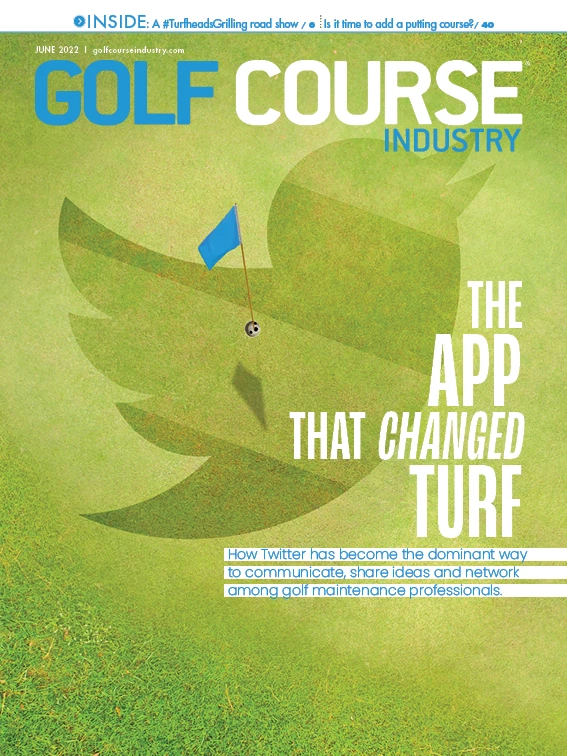

Explore the June 2022 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Advanced Turf Solutions’ Scott Lund expands role

- South Carolina’s Tidewater Golf Club completes renovation project

- SePRO to host webinar on plant growth regulators

- Turfco introduces riding applicator

- From the publisher’s pen: The golf guilt trip

- Bob Farren lands Carolinas GCSA highest honor

- Architect Brian Curley breaks ground on new First Tee venue

- Turfco unveils new fairway topdresser and material handler