Jeff Wagner is proud of his native Oklahoma. It’s where he grew up, attended school and has spent most of his life. He left the state just once to work as the assistant superintendent at The Glacier Club and as the superintendent at Blackstone Country Club, a pair of Colorado courses. Even then, he lived away from Oklahoma for less than a decade.

During his time as a superintendent in the Rockies, Wagner established a reputation as a passionate young voice in the industry. His main goal is to improve the courses he maintains any way he can. Helping turn around a small-town course in his home state in just six years as superintendent is his proudest career achievement.

Just on the edge of the Oklahoma panhandle, Boiling Springs Golf Club, where Wagner serves as superintendent and general manager, is becoming a destination course in an overlooked corner of the Sooner State. Boiling Springs has a Woodward mailing address. The 12,000-resident community is more than a two-hour drive from a major city in every direction. Although it sits on historically important shipping trails and was a hub for trade in the Western United States for decades, Woodward experiences the same isolation facing many small towns.

Boiling Springs opened in 1979 as a par-71 course six miles outside of downtown Woodward. The course is owned by the city, while management is contracted out to companies who handle its day-to-day operations. Green fees are $40 with a cart on weekdays, $45 on weekends.

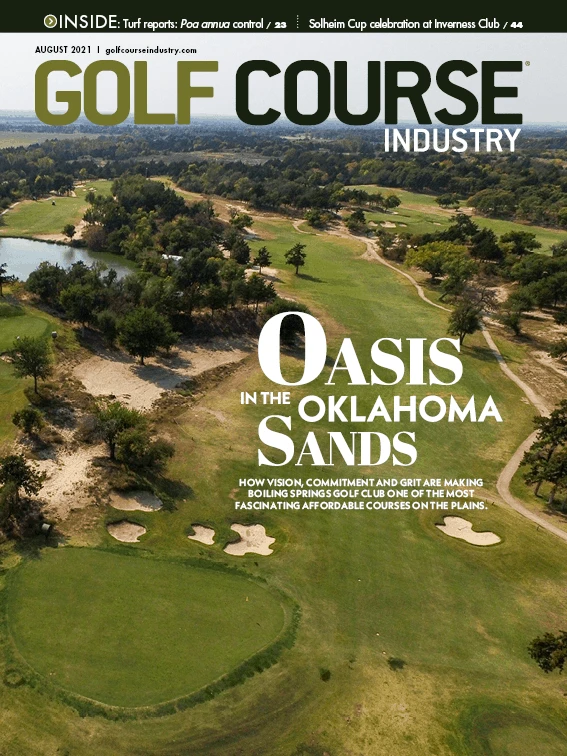

Wagner views the course as a glint in an otherwise unremarkable area of Oklahoma. The course is unlike other clubs in larger cities in the region. It relies less on turf and has spent the last few years cutting in native vegetation and allowing the sandbars stretching from the adjacent Boiling Springs State Park to replace the less-trafficked turf Wagner sees as unnecessary. The result is a wild, sandy and memorable golf experience.

But Wagner hasn’t done it alone. In fact, he wasn’t even the one who began the overhaul of the course. He was the final piece of the puzzle necessary to revive Boiling Springs. John Dunn, one of the original spearheads of the project, hired Wagner in 2015.

A Woodward native, Dunn is the head of Oklahoma City-based Dunn Golf Management. He’s kept a strong connection to his hometown — and especially to Boiling Springs — since his entry into the golf development business in 1997. Dunn has made sporadic visits to his hometown either for business or leisure over the course of several decades. He often played rounds at Boiling Springs on those visits.

While working on a project in Amarillo, Texas, in the 1990s, Dunn and architect Jeff Blume made a detour in Woodward to play Boiling Springs. “(Blume) made the comment on that visit that, ‘Man, this site is elite. If we ever get the chance to work on this, we need to do it,’” Dunn says. “At the time, I just laughed to myself knowing that would be an impossibility and it never even occurred to me.”

Sometimes the impossible comes true. Dunn never actively sought out Boiling Springs. It fell into his lap. Over coffee with a friend from Woodward one day, Dunn learned the funding for Boiling Springs was in danger of being cut. Apparent mismanagement from then-club staff as well as years of economic stagnation had placed the course in a tight spot financially.

Boiling Springs was built during an oil boom in the late 1970s, when towns like Woodward were seeing exponential economic and population growth. The course had been financed with matching local and state funds. Boiling Springs was required to generate a certain gross revenue to keep itself in working order. For the first few years, this model worked as long as the oil industry kept growing. Scarcely does an industry grow forever, and the oil boom subsided by the late 1980s. Without jobs from the boom, people headed elsewhere. Once the money stopped flowing, the course struggled to generate the revenue needed to improve — or even maintain — what it had.

Dunn knew the course entered a perilous state and the comment made by Blume years ago started swirling in his mind. Knowing Boiling Spring rested on pristine land, Dunn contacted local government officials and offered to manage and renovate the course.

The city manager provided equipment, staff and resources to Dunn, Blume and their group and let them handle the rest. Dunn oversaw most of the restoration, while Blume focused on changing aspects of the course that needed enhancement. “The main thing we did was build new bunkering and new greens, because the greens had died several times over the preceding 10 years, it turns out, from a horrible nematode problem,” Dunn says.

It took months of work, but the effort paid off. The year after Dunn became involved with the course, Boiling Springs experienced record revenues and the project seemed like it was on track for success. Then, nematodes resurfaced. The same pests that had killed the greens multiple times were still plaguing the course. After the greens died a second time following the renovation, Dunn’s original superintendent resigned.

Dunn scrambled to hire a new superintendent to keep Boiling Springs running smoothly. He quickly embarked on a national search. Although skeptical, Dunn held out hope for a solid candidate. Little did he know he would find a candidate from western Oklahoma with ample experience in Wagner. After reaching out, Dunn learned that Wagner’s goals for the course aligned with his objectives.

“Jeff (Wagner) showed up on my radar one day and I was so impressed by his résumé that I called him because he’s from western Oklahoma,” Dunn says. “He’s incredibly articulate and energetic and everything you’d be looking for. To find that guy from western Oklahoma is a minor miracle. And then to have a young man with a sense of ownership of pride to work as hard as he has, to try to honor this vision that we all have, I think that’s pretty unique. We have a golf course architect, a golf course superintendent, and developer/owner all completely passionate and driven and unified in our goals.”

As soon as Wagner was hired, he went to work on the first major project at his new course: the systematic removal of thousands of nonnative trees. The eastern red cedar, an invasive species to western Oklahoma, has caused problems at Boiling Springs for years. From Wagner’s perspective, the cedars are like a weed, just much harder to remove. They sucked up groundwater, spread fast and clogged Boiling Springs over three decades. By the time Wagner was hired, there were more than 100,000 red cedars on the course’s 120 acres. “We didn’t anticipate the project taking five years,” Wagner says. “We had nothing to work with. No resources. We just literally pulled 100,000 cedars out of the forest with a couple guys, a tractor and two chainsaws.”

How did the cedar problem get to where it was? Wagner points to irrigation and turf management. When low-traffic areas of turf around patches of trees are watered regularly, the soil becomes ripe for red cedars looking for somewhere to take hold. Spread the process over 35 years, and you get the case Wagner, Dunn and Blume were handed.

In addition to overwatering, Boiling Springs sits in an awkward position for a golf club in Oklahoma. Due to the area’s arid climate, it is tough to have a course entirely covered with standard turf. The winters are too cold for any turf variety other than bentgrass.

How did Wagner plan on preventing the cedars from coming back and cut down on water costs? He began having his team reduce the amount of turf on the course.

Wagner took a page from Blume and Dunn’s book. He saw that the best way to reduce both water use and the amount of bentgrass needed was to highlight the course’s natural beauty. Instead of trying to force turf into an arid area like Woodward, the focus over the last few years has been to scale back and let the sandbars and native grasses take over the scenery. And when Wagner says take over, he means a complete overhaul of the turf around Boiling Springs. “We’re strategically eliminating all of our Bermudagrass roughs,” Wagner says. “We’re cutting in native grass varieties like little bluestem, sideoats grama, blue grama, the natural vegetation drought-tolerant varieties that exist here naturally.”

Wagner’s plan over the next five years is to phase out roughs all together. Bermudagrass is high maintenance and the sands mixed with local grasses are a more cost-effective, eye-catching alternative. His end goal is to renovate the course in the vein of Royal Melbourne, which he considers both the biggest inspiration for the project and closest resemblance to the Boiling Springs environment.

With six years at Boiling Springs complete, Wagner isn’t showing any signs of slowing. Talking about the course excites him and the passion bubbles to the surface as he fits as much as he can into a single sentence. His ideas for the future flow like water, and he wants to bring attention to the course he holds so close to his heart.

“It’s just such a cool place. It’s so cool, man,” Wagner says “It’s reinvigorated my career and made me a better superintendent. There’s diamonds out there in the rough, and we want (people) to go out and look for them.”

Explore the August 2021 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show