At the Country Club of Mobile in Alabama, if you miss the fairway, you are in the rough. Which is exactly as it should be when you have 65 acres of 419 Bermudagrass fairway cut at ½-inch. No more do they coddle the golfers, as they did the first year following a course restoration in 2018, when golfers faced a 1-inch collar of Bahiagrass, with a 4-inch cut behind it. Now the rough is kept at 2 inches: perfect for framing the fairways while keeping the outward areas playable.

Congressional Country Club did away with the intermediate in its recent Blue Course restoration. Veteran superintendent Pat Sisk, CGCS, got rid of it at Milwaukee Country Club during a restoration a few years back. The first change he made at Longmeadow Country Club in Massachusetts when he took over in 2019 was eliminating the intermediate. Minikahda Club (Minnesota), St. Croix National (Wisconsin) Golf Club, Wing Point (Washington) Golf & Country Club, Beverly (Illinois) Country Club. Llanerch (Pennsylvania) Country Club and Bulle Rock (Maryland) are among the many courses that have made the same move.

I cannot tell if I am seeing a trend or advocating a movement. I have always detested the idea of an intermediate cut and for all sorts of reasons – architectural, agronomic and cultural – think it should disappear. Doing away with the intermediate collar around fairways makes for better definition, eases maintenance and makes a stand with respect to defining a proper penalty without coddling wayward golfers. The point, after all, is that there ought to be incentive for hitting fairways and there ought to be a penalty of sorts for missing them.

Culturally speaking, the intermediate cut is a modern indulgence that caters to mediocrity. It’s like your Gen-X parents who are too gutless to tell their kid no. Or the high school principals who award every C-student honorary honors.

Architecturally, it’s also the easiest way to highlight the contours and character of your golf course. If golfers from the tee looking out upon the hole see an array of ½-inch fairway, 1.25-inch intermediate and 3-inch rough they are not going to be able to appreciate the contours as well as someone who sees ½-inch fairway juxtaposed against the rough. Even if the height differential between intermediate and major rough exceeds that of the intermediate against the rough, the effect is lost because of the profusion of contrasting mowing heights, plus the fact that the second delineation usually involves the same turf types with the same color tones. Going directly from fairway to rough maximizes the contrast and enhances a sense of ground contour, surface flow and topography.

In terms of maintenance, that extra swath of in-between turf requires additional mowing and a separate machine. Eliminating that cut will save on labor.

The key to getting rid of the transitional cut is to expand the fairways to cover that area. The expansion will be anywhere from a 10 to 20 percent of your fairway. While there is some increase in cost associated with that much additional fairway management, the marginal increase will still constitute a savings over how you are treating your intermediate.

I normally advise full disclosure to a membership or daily-fee golfers in matters of maintenance. In this case I’d focus more on how you are going to widen out the fairways and not get lost in the details of the transition process. This is one area where the complexity of transition and the advantages of the move need to be experienced rather than explained in advance.

It might be helpful here to adjust your mowing heights. If you have been keeping that primary rough at 4 inches, a cut back to 2 or 2 1/2 inches (or 3 max) would be advisable.

The key to success is widening your fairways. I know of several superintendents whose effort at getting rid of the intermediate failed because they converted that area to rough instead. Big mistake.

The one area of resistance that will arise involves courses with dramatically side-sloped fairways and shots that land in the fairway and run down and out to the point where they just make it to the newly defined primary rough on the low side. That’s because the ball, following gravity and slope, will nestle down into areas where water and fertilizer accumulate.

The fact is that such cases of overly punitive lies on marginal shots are one of the idiosyncratic features of golf. The overall benefits – better design awareness, easier maintenance – far outweigh the marginal cases.

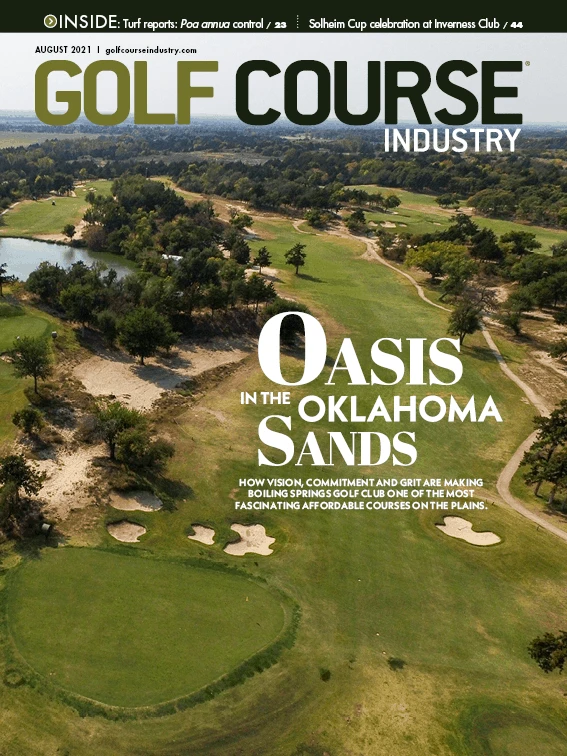

Explore the August 2021 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- PBI-Gordon receives local business honor

- Florida's Windsor takes environmental step

- GCSAA names Grassroots Ambassador Leadership Award winners

- Turf & Soil Diagnostics promotes Duane Otto to president

- Reel Turf Techs: Ben Herberger

- Brian Costello elected ASGCA president

- The Aquatrols Company story

- Albaugh receives registration for chlorantraniliprole