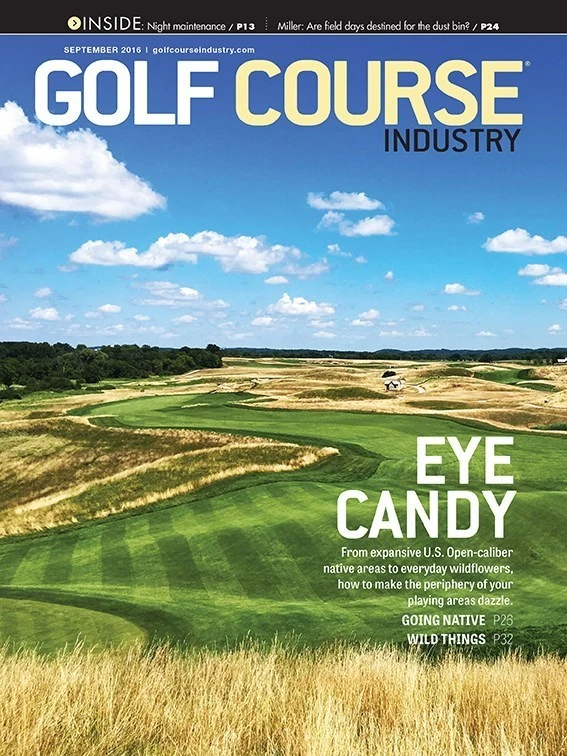

It’s the Heartland’s version of an ocean. Hues change depending on the season. Listening to it flutter offers therapeutic value. Roam it once and you want to experience it again. Those fortunate enough to work amongst it crave it when it temporarily goes away.

It’s so serene. So natural. Some might say it’s so Midwest. It holds the potential to enthrall millions next June.

And learning how to maintain it is consuming.

Pebble Beach and Torrey Pines have water views. Pinehurst and Oakmont have storied histories. Erin Hills has expansive native areas. These aren’t just let-them-go-wayward spots on any other course opened in the mid-2000s. Superintendent Zach Reineking and his team are managing the frame to the first picture to host a U.S. Open in Wisconsin.

The frame, though, might be what the world remembers about Erin Hills. How many courses have 150 total acres, let alone 150 of maintained fescue native areas? The thought makes you want to grab a baler or two.

Speaking of balers, Erin Hills owns two. But before we get to the folksy part of this story, let’s reveal the reality associated with pleasing native areas. “You really need to emphasize to a membership or ownership that it’s a two- or three-year process,” Reineking says.

Or sometimes longer.

Reineking and assistant superintendent Alex Beson-Crone, a pair of Wisconsin natives and University of Wisconsin graduates, arrived at Erin Hills in 2005 and started growing in a Dr. Michael Hurdzan, Dana Fry and Ron Whitten design attracting curiosity before its 2006 opening. Imagine being in turf school one year and heading the agronomics of a new course with U.S. Open aspirations a year later. Now imagine being greeted by fine fescue fairways in a Heartland growing environment and rugged native areas on the periphery.

Some might say the job required a machete. Others might say patience trumps any piece of equipment.

Scraggly start

Hurdzan and Fry, partners at the time, and Whitten, the longtime Golf Digest architecture editor, designed a minimalistic golf course for then-owner Bob Lang on a grand scale consisting of 652 rolling acres. Part of the philosophy behind Erin Hills involved framing the course with areas that required almost no maintenance. “When you are talking about a true native area, it was a true native area because nothing was done to those,” Fry says. “And when it opened, it was so difficult that the stuff in places was two, three, four feet tall. It was just whatever grew naturally. You could lose a human being in the stuff, let alone a golf ball.

Broomweed, Johnsongrass, Birdsfoot Trefoil. Whatever grew in Wisconsin pastures, emerged in Erin Hills. Reineking describes the original native areas as “very dense, very unmanageable,” and crew used secondary mowers to try to keep heights at 5 inches. Complicating matters: the USGA was coming to town. The organization awarded Erin Hills the 2008 U.S. Women’s Amateur Public Links Championship before the course opened. The prestigious U.S. Amateur was to follow three years later. And Lang, who started encountering financial difficulties, liked the aesthetics of patches containing goldenrods and Queen’s Anne Lace. “There was just no way we could play the amateur with our natives being so unruly,” Reineking says.

In the winter of 2008, through the use of Roundup and controlled burning, areas surrounding the patches were killed, thus beginning a conversion to fescue-dominant native areas. The conversion continued throughout 2009 and 2010, with Erin Hills receiving a major boost in October 2009 when Wisconsin businessman and Milwaukee Country Club member Andy Ziegler purchased the course. Ziegler infused Erin Hills with needed capital and closed the course until July 31, 2010 for renovations. Erin Hills reopened as a walking-only facility, a move designed to protect the fine fescue fairways.

Fescue of a different kind started filling peripheral areas as the U.S. Amateur approached. And, again, it wasn’t providing an ideal frame – yet. “It was super thick,” Reineking says. “I mean it was unplayable thick. If you walked through some of the areas, you would trip and fall.”Another controlled burn in the winter of 2010 allowed Erin Hills to handle the U.S. Amateur, which served as a trial for a bigger tournament. The USGA had awarded Erin Hills the 2017 U.S. Open on June 15, 2010.

Spraying and baling

Quackgrass, a gnarly, cool-season perennial species, started becoming a significant problem during the conversion, and the increased presence of it was hurting Erin Hills’ reputation. “I recall reading a blog on Golf Club Atlas where somebody posted: ‘Just played Erin Hills. They have such a problem with quackgrass. They will never figure it,’” Reineking says.

Instead of taking the quackgrass discussion personally, Reineking dabbled with multiple herbicides, including Fusilade, which is primarily used in ornamental settings in Wisconsin. Part of the experimenting involved spraying a Fusilade trial on a part of the course with intense quackgrass and Reed canarygrass establishment. Accompanied by a sales representative who introduced him to the herbicide, Reineking casually returned to the plot, placing half of his body in the treated area and the other half in an untreated area. The difference was striking.

“The Reed canarygrass was over my head. We got through this Reed canarygrass to this strip, which was no more than 20 feet wide, grass was this tall,” Reineking says while pointing between his ankles and knees. “There’s a picture of me standing in this area with the Reed canarygrass over my head and half of my body in the area where it’s stunted that was maybe 6 or 8 inches tall.”

Fusilade has since become a staple of Erin Hills’ native area management program. The herbicide is typically applied twice in the spring and twice in the fall. Erin Hills purchases 50 cases per year, and Reineking says the herbicide has “basically eradicated all of the quackgrass off the golf course.” He adds Fusilade controls “the vast majority of invasive grasses” that might mix with the fescue in the native areas. Reed canarygrass, Broom, Birdsfoot Trefoil, thistle and milkweed are among the other weeds that compete with the fescue. “If it’s not fescue, we want it gone,” assistant superintendent Adam Ayers says.

Knowledge from neighbors further helped rebuild the native areas. Erin Hills is in Hartford, Wis., a rural community 35 miles north of Milwaukee. Conversations with USGA Green Section agronomist Bob Vavrek about a pair of Minnesota courses using farming practices to thin native areas led to members of the Erin Hills team visiting a local farm to observe a hay baling operation. The farmer established a test program at Erin Hills. The success of the program convinced Reineking to expand the operation.

Mechanic Don Heesen found a retired farmer selling the necessary equipment – mowing conditioner, hay rake and baler – for $3,000 on the Internet.

Erin Hills collected 3,480 bales of fescue in 2014. Purchasing a second baler allowed the crew to collect 5,000 40- to 50-pound bales in 2015. Baling begins when the course closes in October, and the process takes 2 ½ to 3 weeks. The mowing conditioner cuts the fescue. The plant then dries for 36 hours before being flipped with a hay rake. The dry material is baled.

“It has kind of thinned out these native areas,” Reineking says. “Our philosophy is you are not returning all the plant material, in essence, you are creating an anemic soil. If you were just to mow these areas down, that plant material would break down. That amount of N in the plant would go back into the soil and keep these areas kind of thick. By removing all that plant material, we are actually taking some of the N out of our soil.”

Baling is a zero-waste endeavor because Erin Hills exchanges its bales with a local Amish community. In return for the fescue bales, Amish workers build wood benches and garbage cans and complete pressure washing tasks for the course. The Amish use the fescue for animal bedding.

Thinner and thinner

After nearly a decade of frustration, experimentation and transformation, Reineking and his team have developed a rhythm for maintaining fescue native areas. Stands, which include a mix of hard fescue, sheep fescue and creeping red fescue, are 3 ½ to 4 inches high when winter ends. They are mowed to 2 inches in anticipation for their annual greening. Seedheads become noticeable in mid-May and by the first week of June they typically look purple. Later in the month, a wispy, brown fescue dots the course, although the presence of sheep fescue and creeping red fescue create blue and red tinges, respectively, Beson-Crone says.

We visited Erin Hills in late July, and an overwhelmingly brown appearance proved stunning. As we walked the fifth fairway alongside Beson-Crone, we paused and listened as the fescue made noises resembling gentle waves hitting sand. “The way it blows in the wind … It’s almost like hypnotic sometimes when you are looking at,” Beson-Crone says later in the day.

Beson-Crone has observed the fescue nearly every working day of his life for the past 11 years. The fescue’s appearance is weather-dependent, and it’s anybody guess how it will look June 15-18, 2017. The fescue had a brown appearance on the U.S. Open days this past summer, Beson-Crone says. But he adds, “this year was probably the earliest that we were brown.”

Pondering mid-June hues beats previous conversations involving Erin Hills’ native areas. Beneath the current beauty, rests memories of ball-losing, scrape-inducing six-hour rounds of golf. Fry has visited thousands of courses in more than 100 countries, and he hasn’t seen a course with a comparable acreage of maintained native areas. He says the combination of Reineking’s persistence and Ziegler’s financial commitment are creating an enduring feature.

“It’s just a surreal experience when you are out there this time of the year, and it’s all the brown grass and it’s waving in the wind,” Fry says. “How many places do you go and play golf and see that much of it?”

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the September 2016 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Carolinas GCSA raises nearly $300,000 for research

- Advanced Turf Solutions’ Scott Lund expands role

- South Carolina’s Tidewater Golf Club completes renovation project

- SePRO to host webinar on plant growth regulators

- Turfco introduces riding applicator

- From the publisher’s pen: The golf guilt trip

- Bob Farren lands Carolinas GCSA highest honor

- Architect Brian Curley breaks ground on new First Tee venue