Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the March 2025 print edition issue of Golf Course Industry under the headline Municipal golf’s moment.

Understanding the reach, influence and advancement of municipal golf in a post-pandemic society requires beginning near the middle.

Lincoln, Nebraska, lies 165 miles northeast of the geographic center of the contiguous United States. With 81 holes scattered across five contrasting courses, Lincoln City Golf is the largest municipal golf operation near the mainland’s geographic nucleus.

Denizens of the growing Heartland city pack the system’s courses. Avoiding flying Top Flites and Titleists requires rising early in the summer — golf course maintenance crews rev equipment at 5:30 a.m. to beat the golf barrage — or layering up during chillier months. “You want to give your retired guys a chance to have their coffee,” says Chad Giebelhaus, one of the city’s four head golf course superintendents, describing the peak-season morning hustle. “But it’s, ‘OK. You have to go. We have to go.’”

On an early December afternoon, with turfgrass still exuding robust-green tinges and temperatures warm enough to produce unfrozen playing surfaces, Pioneers Golf Course offers a venue for something uncommon from April through November: a quiet walk. Only a dozen golfers occupy the 95-year-old course surrounded by a nature preserve and 144-year-old brick factory. Seas of shaved prairie grasses dot the landscape’s interior.

Evidence of golfer wear is challenging to detect, a miraculous feat manufactured by superintendent Matt Noble’s team considering a warm and dry fall increased play volumes. Lincoln City Golf reported Pioneers, the patriarch of the city’s municipal facilities, supported 51,774 rounds in 2024. The city’s other three 18-hole courses, Holmes, Highlands and Mahoney, also surpassed the 50,000-round mark. Add in the 30,525 rounds at Jim Ager, a beginner-friendly, par-3 course between ballfields and homes, and Lincoln City Golf supported 235,012 rounds and generated $1,063,413 in profit last year.

Lincoln isn’t the only city where municipal golf is thriving. One hundred and thirty years after New York City introduced the concept of government-supported golf at Van Cortland Park Golf Course, America boasts a record 2,939 municipal courses, according to the National Golf Foundation. In an era where course contractions outpace openings, the municipal golf supply has increased by 140 courses since 2004.

The finances are equally encouraging. Around 75 percent of municipal facilities collect enough revenue to cover onsite labor and maintenance expenses, according to the NGF. Empowering leaders turning to highly qualified professionals to oversee municipal facilities help golf stay affordable in many places. The average 18-hole municipal course green fee remains below $40; the quality produced by superintendents and their teams far surpasses the meager green fees.

Observing activity on America’s municipal golf grounds makes the numbers more convincing. Over the final five months of 2024, we visited people and places responsible for municipal golf’s moment. The journey makes us bullish about how golf and government can cohabitate to uplift the game and communities.

New Jersey is home to renowned private clubs, heavily played municipal courses and the bluntest people in the golf business. Garden State golfers and agronomists aren’t shy about sharing candid thoughts — even when job looking.

Tim Christ sought a position with stability and support during a 2009 job search. The only thing he saw while touring the Essex County-owned courses was dead grass. OK, he also noticed thriving crabgrass and goosegrass in key playing areas. “They took me around,” Christ says, “and I wanted to throw up. I said to my wife, ‘There’s a 98 percent I’m not taking this job.’”

The open job involved overseeing the county’s three courses: Francis A. Byrne, Hendricks Field and Weequahic. The courses featured a golf trifecta in Golden Age design roots. Charles Banks designed Francis A. Byrne and Hendricks Field. Former Baltusrol pro George Low plotted Weequahic. Years of neglect, though, upset Christ’s strong stomach.

A starting offensive lineman at Rutgers University in the 1990s who launched his golf maintenance career and quickly ascended at revered private clubs, including Merion, Pine Valley and Hamilton Farm, Christ mulled cancelling an in-person interview with county officials. Christ ultimately kept his interview slot out of respect for Stephen Kay, the New Jersey-based architect who encouraged him to apply for the job. Architects can connect superintendents with potential opportunities, and Christ didn’t want to sever a relationship.

Following a few tense exchanges, Christ told county officials what they needed to hear. “I said, ‘You have some really cool bones out here, they are really cool Banks courses,’” Christ says. “But there’s dead grass everywhere, you have nobody with a turf degree. I just started going through the litany. Everybody just shut up and let me talk. I said, ‘Your agronomy is terrible. I don’t care how much money you throw into it, if you don’t have guys who have degrees and can grow grass, none of it matters.’”

The bluntness combined with a terrific résumé landed Christ the job as the county’s director of golf operations responsible for overseeing operations at the three courses. The county now employs seven managers with turfgrass degrees.

Under the leadership of longtime county executive Joseph N. DiVincenzo Jr., Essex County has invested more than $20 million to revitalize the three courses. Kay guided each project, with work concluding at Hedricks Field and Francis. A. Byrne in 2021 and 2023, respectively. A massive renovation at Weequahic concludes this summer. “I kind of look at us like a mini-Bethpage, because Joe has put the money in,” says Christ, referring to famed Bethpage State Park, the five-course municipal facility on Long Island set to host the 2025 Ryder Cup.

A tour of Francis A. Byrne with Christ last August illustrated what municipal golf has become in New Jersey’s third-most-populated county.

For starters, the course is empty. A day following the tour, Francis A. Byrne hosted the New Jersey State Golf Association Public Links Championship. The county’s desire to present tidy conditions to a statewide golf audience gave superintendent Chris Krno’s team a golf-free maintenance block one day before the tournament.

Christ and Krno briefly reflected on the course’s metamorphosis during a conversation to the left of the third green. The third hole is an uphill par 4, featuring a punchbowl green, a Golden Age template revived by Kay.

Krno was Christ’s first major hire, leaving a position as a head assistant at a nearby private club to become Francis A. Byrne’s superintendent. He’s in his 16th season in the role. The job features a supportive boss who understands the value of preserving a Banks design. Nicknamed “Steam Shovel” because of a penchant for crafting bold features, including nearly upright bunker faces, Banks’ legacy predominantly involves his work at exclusive clubs. “You could tell this was cool,” says Krno, recalling his first course tour with Christ in September 2009. “I kept telling myself if I was here long enough, we would get there.”

From the third green, a golfer trudges to the upper part of the course, which borders the private Essex County Club, another Banks design. Essex County acquired the course now known as Francis A. Byrne from the private club in 1978. The ninth hole connects the upper and lower portions of the course. The downhill par 4 includes cross and approach bunkers, a horseshoe-shaped green, and thumbprint inside the putting surfaces. The tee provides a fabulous view of the hole and the neighborhood surrounding the course. “This looks great in October with the fall color,” says Kay, who joined the August course tour on the eighth tee.

The ninth hole looks great in the summer heat, too. “This whole design was a group effort,” Kay adds. “I wasn’t the dictator, nor was Tim, nor was the shaper. It was always a big team effort. We kept asking each other: What do we think is going to look good and how can we maintain it?”

Christ and Kay hustle through the back nine in electric carts — they want to visit Hendricks Field before northern New Jersey traffic thickens — but stop at the 17th tee, which parallels the second hole. The 17th is a reverse redan; the second is a giant Biarritz. The par 3s provide enthralling on-the-ground possibilities, dynamic mowing lines, polished bunker complexes and carefully sculpted mounding. Golfers from Newark, the Oranges, Montclair and nearby municipalities once needed pricey private-club memberships to experience high-quality template holes.

“How many places have done anything like this?” Christ asks.

Jeremy Phillips and Kevin LaFlamme experienced a similar transformation on a compact golf scale at Coonskin Park, a 1,000-acre green space operated by Kanawha County Parks and Recreation. With 173,746 residents, Kanawha County is West Virginia’s largest county and home to the capital city of Charleston.

Tucked in a valley along the Elk River beneath Interstate 79, Coonskin Park supports a pool, wedding garden, hiking trails, disc golf, picnic shelters, tennis courts, horseshoe pits, athletic fields, driving range and an awesome 9-hole, par-3 golf course. Phillips and LaFlamme lead a small team responsible for maintaining the course and the park’s other recreational amenities. In the summer, the crew swells to around eight employees. In the shoulder seasons and winter, only one other year-round grounds employee works alongside the duo.

Whoever arrives first — and spotting the park’s entrance can be tricky because dense morning fog frequently engulfs the valley — unlocks a gated bridge over the Elk River. The unlocking signifies the beginning of the work and recreational day. “As soon as we open the gates,” LaFlamme says, “we’ll have joggers and walkers come into the park.”

On days warm and dry enough to play golf, the work hustle — like it does in Lincoln, Nebraska; Essex County, New Jersey; and thousands of other municipalities — immediately commences. Team meetings and social banter must be saved for another part of the municipal golf workday. “When you come in, there’s no, let’s grab a coffee, sit around and talk about what we’re going to,” LaFlamme adds. “It’s, let’s go.” Busy municipal golf courses hurt coffee industry sales.

Spending two decades as co-workers makes Phillips and LaFlamme equipped to navigate the frantic pace of a municipal maintenance morning. The pair developed as turf professionals together at Edgewood Country Club, one of Charleston’s two private clubs. Phillips started his career raking bunkers, took an interest in the industry, and steadily advanced through the club’s turf hierarchy. He left a position as Edgewood’s first assistant in 2020 to join LaFlamme at Coonskin Park. Leading a maintenance operation at a park preparing for a big golf project intrigued the duo. Phillips oversees the daily efforts on the short course, while LaFlamme scurries between park amenities.

The Short Course at Coonskin debuted in May 2023. A thorough review of the park’s golf future stems from a devastating 2016 flood that ruined the back nine and irrigation system of what Kanawha County Parks and Recreation director Jeff Hutchinson described as a “very plain and vanilla” 18-hole executive course. Hutchinson’s department manages and maintains 3,000 acres across four locations with just 19 full-time employees. When Hutchinson arrived in 2002, Kanawha County owned and operated 54 holes. The Great Recession pinched the West Virginia economy, and the county has trimmed its golf volume to 27 holes: 18 regulation holes at Big Bend Golf Course and the 9 holes over 13 acres at Coonskin Park.

“We have had to be super creative,” Hutchinson says. “We sold a golf course and closed another one. That was hard on me. I’m a golf pro. But in the last two decades, we’ve done what’s best for everything here. We’ve asked ourselves: How can we still serve the public and still do something that’s really good for golf?”

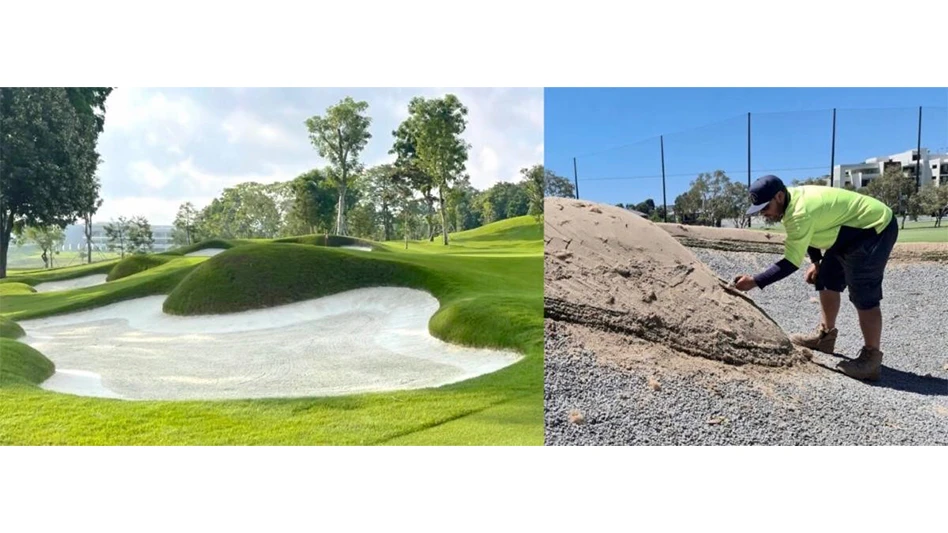

Funding for Coonskin Park’s golf overhaul emerged when the Kanawha County Commissions approved using $1.2 million from the county’s America Rescue Plan haul toward the project. West Virginia native Kelly Shumate designed an imaginative-to-play and efficient-to-maintain layout with Golden Age-inspired green complexes. Todd Godwin and his TGC Construction team built the course in about 50 working days.

The course Phillips and LaFlamme maintain represents a stark contrast to what they had been trying to keep playable. Before Phillips accepted a job at Coonskin Park, he fielded multiple calls from LaFlamme, including one where his friend compared the greens to paper plates resting on a table. Wilted and decaying turf covered the surfaces. “Kevin came over a few months before me and he sent some of these pictures and he was like, ‘Oh, man, I might have gotten in over my head,’” Phillips says. “I said, ‘No, this going to be a good opportunity, especially with the way they were talking about the new construction.’”

Vibrant bentgrass blends now cover greens, approaches and tees, as beginners learning the game and enthusiasts honing shots experience holes such as the ninth, a 102-yard teaser with a punchbowl green complex. Coincidentally, the ninth hole at The Greenbrier’s famed Old White Course also features a punchbowl green complex. Municipal layouts such as the Short Course at Coonskin make Golden Age experiences affordable for golfers who might never be able to drop $500 to play their state’s prized resort course.

When they have time to look around, Phillips and LaFlamme notice golfers wearing everything from polished Foot Joys to tattered sandals enjoying their versatile work. Ensuring awesome golf experiences for the Kanawha County, West Virginia, masses means the mechanic, irrigation technician, spray technician and superintendent possess the same name. Jobs protecting beloved community assets induce frequent fatigue and abundant fulfillment.

“All in all,” Phillips says, “it’s been a pretty good little journey.”

Generalists proliferate municipal golf, including in Lincoln, where Casey Crittenden oversees four superintendents operating without mechanics and technicians. Crittenden is Lincoln City Golf’s maintenance coordinator. He joined the system in 2014, when play totals for the 18-hole courses settled in the low- to mid-40,000s depending on the weather. Generating enough revenue to cover annual expenses represented an operational win during the 2010s.

Before the pandemic, municipalities leaned on employee ingenuity to stay afloat. Following the pandemic, employee ingenuity helps municipalities increase golf windfalls. Lincoln City Golf’s 18-hole facilities handle robust play with crews consisting of just three full-time turf employees. Municipal golf’s moment is a people-driven triumph.

“We’re an enterprise system,” says Crittenden, referring to Lincoln City Golf’s self-sufficient operating structure, “and it’s all hands on deck. You really have to be a well-rounded individual to be a superintendent here for the City of Lincoln.”

Giebelhaus begins mornings at Highlands by guiding a team of seasonal employees supplementing the meager full-time staff to the right spots on a 1990s links-style course with around 115 maintained acres. He then starts changing cups, a job that allows his trained eyes to see every green at least once per day. He will then help fix irrigation snafus or execute some other type of targeted digging before ending days with 30 minutes of office work.

Less than 10 miles east of where Giebelhaus digs, superintendent Scott Kennedy often grabs a rake and prepares Mahoney’s two dozen bunkers ahead of play. “Honestly, bunkers are one of my favorite jobs,” Kennedy says. “It plays into my OCD. Casey will come visit and find me in a bunker somewhere. He must think I live there sometimes.”

When Crittenden visits Pioneers, he never finds Noble in a bunker. Lincoln’s oldest municipal course packs abundant charm due to varied topography, so a golfer might never realize they are playing a course devoid of bunkers. Noble views himself as an extreme generalist. “I like to be everywhere,” he says. “I don’t have a lot of younger help, so I try to jump in and help my guys do a lot of stuff, so that not everybody is doing the same job. The labor part is one of the parts of the job that I love.”

Holmes’ Zac Caudillo spends more time than his Lincoln City Golf superintendent peers repairing irrigation issues. But a redistribution of his personal labor looms. The 60-year-old course’s irrigation system is scheduled to be replaced as part of a 10-year capital improvement plan revised in 2023. Modest surcharges, currently $2.25 for 18-hole rounds and $1.50 for 9-hole rounds, fund capital improvements, with Lincoln City Golf spending more than $3.6 million on upgrades since 2016. The system has used profits generated from 2020 and subsequent years to establish and expand a financial buffer in the form of a reserve now exceeding $800,000, according to golf operations coordinator Wade Foreman.

Modest also describes Lincoln City Golf green fees: the highest, peak-season, busy-time green is under $40 at all four 18-hole courses. “People might come from out of town or other places, and they see the green fees and they’re like, ‘They are really low. I don’t know what I’m going to get,’” Kennedy says. “They then see the courses and they’re like, ‘Wow.’ They are surprised by how good the courses are and what they pay to play.” Similar affordability exists in Kanawha County, West Virginia, and Essex County, New Jersey. The Short Course at Coonskin costs $20 to play, while the 18-hole green fee at Francis A. Byrne ranges from $30 to $80.

Affordable green fees and high-traffic locations yield little respite for superintendents and their teams: a municipal course receives 30 percent more play than a daily-fee facility, according to the NGF. A municipal course superintendent might not reflect when changing cups, fixing an irrigation leak, raking bunkers and compiling invoices on the same day, but their efforts create a mix of affordability and quality boosting the game’s popularity.

Consider the masses fortunate.

“Cities that are growing and vibrant need to have different activities for different citizens,” Foreman says. “Golf is an important piece of that anywhere in the country, and people need a place to play. We try to provide quality courses at an affordable rate for golfers and citizens in Lincoln.”

Explore the March 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Bloom Golf Partners adds HR expert

- Seeking sustainability in Vietnam

- Kerns featured in Envu root diseases webinar

- Toro continues support of National Mayor’s Challenge for Water Conservation

- A different kind of long distance

- Golf Construction Conversations: Stephen Hope

- EnP welcomes new sales manager

- DLF opening centers in Oregon, Ontario