A mom. Five young children. All toting golf clubs. Brisk, judgment-free play.

Even somebody hardened by a half-dozen grow-ins, 30 years of maintaining golf courses in the Arizona sun and a few years in turf equipment sales paused from his work to admire the scene on an early January day at a course in a municipality called Paradise Valley. “You don’t ever see that on a regulation course,” Mountain Shadows superintendent Ron Proch says.

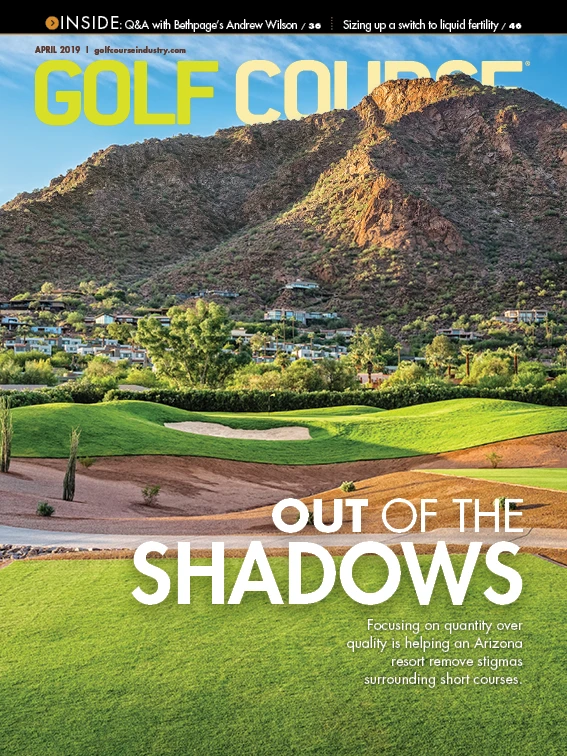

Nestled between a pair of desert mountains, the compact facility where Proch works is changing golfer and operator perceptions. Dozens of par-3 courses have been crafted or revamped during the industry’s current renovation wave. But Mountain Shadows welcomes all: it’s a place where a mother and five children, or somebody introducing the game to his or her significant other, or foursomes looking to play 18 holes in less than three hours can hit shots on intricately maintained surfaces.

Mountain Shadows is a high-end par-3 course for the masses. Neither memberships nor room stays are prerequisites for tee times. Since his arrival as superintendent on June 22, 2016, Proch has been forced to rethink practices and principles.

Proch left a job selling Jacobsen equipment in Northern California to become the first superintendent in Mountain Shadows’ second life. The swanky Arizona property, which also features a resort and seven-figure real estate offerings, received an overhaul by Phoenix-based architect Forrest Richardson, who holds a strong connection with a major piece of the course’s first life, original architect Arthur Jack Snyder. Proch and Richardson previously worked together on multiple projects, including the Wigwam in Phoenix’s west suburbs.

A unique construction/management model further intrigued Proch. Securing Landscapes Unlimited as the golf course builder, thus ensuring the project was completed within the developer’s preferred timeframe, resulted in Mountain Shadows agreeing to a long-term maintenance contract with the company. Proch, a Landscapes Unlimited employee, oversees the maintenance of the golf course and resort grounds.

“I wanted to get back to the area,” Proch says. “One of my friends called and told me about this. I said, ‘Who’s building it?’ He said, ‘Landscapes Unlimited.’ Then, it was ‘Whoa,’ when I found out Forrest was the architect. I flew here and walked the property. It was pretty cool.”

While some industry veterans might shun an opportunity at a par-3 course, Proch embraced working at a non-traditional facility. “I have been here since Day 1,” he says, “and I believe in this. I believe this is the future.”

Short yardage, big potential audience

What’s different about Mountain Shadows?

For starters, the footprint. The course consumes just 33 desert acres. Realizing potential dilemmas surrounding water, even in a state with proactive resource management plans such as Arizona, Richardson reduced maintained acreage to 13½ acres.

Richardson’s work represents a modern version of his mentor’s vision. “What Jack accomplished in 1961 was way ahead of his time: 18 holes on 40 acres that you could play in 2 ½ hours with your grandkids, wife, whomever,” he says. “The concept that’s here today is the same concept that was hatched in the ’60s.”

Before the renovation, Mountain Shadows was classified as an executive course, playing to a par 56 because of two par 4s. The renovation transformed Mountain Shadows into a layout consisting entirely of par 3s. Richardson says he had conversations with Snyder about removing the par 4s in 2002, three years before Snyder’s death.

The revamped course includes forward, middle and back tees, with total yardage ranging from 1,735 to 2,310. From the forward tees, the longest hole plays 150 yards, the shortest 50. From the back tees, the longest hole can be stretched to 220 yards, the shortest measures 75.

Par-3 courses comprise a small portion of the U.S. golf supply – just 514 of the country’s 14,794 total courses, according to the National Golf Foundation’s 2018 “Golf Facilities in the U.S.” report. “This is one of the few high-end, 18-hole par-3 courses in the world,” the well-traveled Richardson says. “You can count them on one hand. You can do a 13-hole par-3 course at Bandon Dunes, because of the 18-hole courses there. You can do the Cradle at Pinehurst, which is 10 holes, because you have all these other courses to play.”

Richardson adds that offering 18 holes, instead of nine or 15, gives Mountain Shadows “substance” as a standalone facility. It takes most golfers between two and three hours to complete an 18-hole round, according to director of golf Tom McCahan. Providing 18 holes that can be played in under three hours allows Mountain Shadows to offer more and later tee times than other facilities in the competitive Phoenix-Scottsdale market. Quick rounds help attract summer play, despite average high temperatures exceeding 100 degrees in June, July and August.

“Something like this could be viable elsewhere, but what really makes this work is this Phoenix-Scottsdale market,” Richardson says. “You get a lot of buzz being in a golf market. If you tried doing this in the middle of nowhere, you would have to have a different angle to it. This is a market where you can play virtually every day.”

Mountain Shadows sells rounds via dynamic pricing, with most online tee times ranging from $35 to $65 depending on time, day and season. The course averages around 1,000 rounds per week this past winter, according to Proch.

Mountain Shadows doesn’t have a narrow audience. Beginners, juniors, seniors, high-handicappers, couples, families, low-handicappers and Arizona-based celebrities (Arizona Cardinals wide receiver Larry Fitzgerald visits frequently) experience the course on a typical day. A group of local golf professionals even uses Mountain Shadows for regular Tuesday skins games.

“Year over year, we’re getting more play,” says McCahan, who arrived in 2016 after 25 years at The Boulders, a 36-hole facility north of Phoenix. “The stigma of it being a par-3 course is being overcome, but it’s still out there. Some people think, ‘If I can’t hit my driver, I’m not playing.’ But word is getting out that you can get around here and have a fun experience in two to three hours.”

The ‘high-end’ experience

Quality course conditions and interesting architecture are helping Mountain Shadows remove stigmas associated with a par-3 golf course.

When fully staffed, Proch leads a 12-person team responsible for maintaining the golf course and resort grounds. As part of a $100 million overhaul, Dallas-based Woodbine Development Corporation and Scottsdale-based Westroc Hospitality also introduced a new 183-room resort in 2017. Proch devotes four employees to maintaining the resort grounds.

The other eight workers spend most of their time maintaining the golf course. The practices implemented by the crew contrast most standalone par-3 courses, thus leading to the “high-end” label used by Mountain Shadows officials.

The crew uses walk mowers on greens and rolls the surfaces “a minimum of three times per week,” Proch says. For events such as the high-stakes skins games involving local professionals, Proch says green speeds can exceed 12 feet on the Stimpmeter.

Walk mowers are also used on tees. Playing surfaces were overseeded last fall, enhancing course aesthetics this past winter. TifDwarf Bermudagrass is the base surface on greens; 419 Bermudagrass is the base surface on tees, surrounds and approaches.

Richardson designed a practice green by the pro shop and outdoor bar and a feature called “The Forrest Wager” between the 17th and 18th holes. The 20 greens average 6,100 square feet, which is comparable to a regulation course, although Richardson concedes green size is a future concern because of heavy play.

“You can always play Monday Morning Quarterback and think about different things,” says Richardson, who worked within a $3.5 million construction budget. “Would it be nice to have more budget? Maybe. Would it be nice to have had more land? Maybe. My biggest regrets here are the green sizes. Each one could be a thousand square feet more. I would be happier, Ron would be happier, probably the golfers would be happier because it would handle wear better.”

Richardson might be his toughest critic. Green complexes are strategic with memorable features, including a Biarritz and punchbowl. Room to place pins in several spots on each green prevents frequent customers from playing reoccurring shots. The 13th and 14th greens are combined with a small bunker sitting in the middle of the surface. Richardson placed tees in dynamic spots, giving golfers varied views of Camelback Mountain to the south and Mummy Mountain to the north.

A compact layout promoting swift rounds means the crew must hustle – and daily work doesn’t go unobserved. “On such a small, tight site like this, there’s nowhere for the crew to hide,” Richardson says. “On a 200-acre golf course or a 160-acre golf course, you can sort of hide.”

The crew begins at 5 a.m., with Proch devoting one worker to each of the following tasks: mowing greens, mowing collars and approaches, mowing tees, raking bunkers, and changing cups. Tee times commence at 7:30 a.m.

The 18 bunkers – a number Richardson kept modest to create maintenance efficiencies – are protected by the Better Billy Bunker system. Bunker, tee and cart path edges are maintained once play begins. Decomposed granite requiring grooming and weeding covers non-turf areas along the course.

Golfers playing 18 par-3 holes produce thousands of divots. Following morning assignments, one worker will spend the rest of the day mixing seed and sand and filling patches. “The No. 1 hardest challenge we have is filling divots,” Proch says.

Proch notices more divots as the new Mountain Shadows ages. They are signs of a small course developing a big reach.

“I have been at places where the budget has been $450,000, and I have been at places where the budget was $2.4 million and I had 42 people,” Proch says. “I didn’t change the way I thought. Now, can you do more projects? Sure. But I’m going on my third year here. What this originally started as with what the job description was, what we were going to do to the golf course and how we were going to maintain things to what it is now … I would say our budget and manpower has increased 40 percent since Day 1.”

Maintenance as a priority

Paul R. Van Buren describes his experiences leading a team responsible for maintaining a high-end par-3 course in Virginia.

About 20 miles west of downtown Richmond, Va., out in cherished horse country, past the county water lines and fiberoptic communication wires, there’s an inconspicuous set of four mailboxes marking the entrance to a piece of land I’ve been responsible for maintaining over the last 15 years. A keypad lays hidden inside a hedge protecting our entrance. Two stone columns flank the metal entrance gate, on the left, “Kanawha,” on the right, “private.”

The unmistakable look of confusion permeates when others learn I work at a “high-end,” private 9-hole par-3 golf course. Most don’t even know it exists, let alone understand the nuances around such a unique golf setting. I have experienced the luxury of overseeing the property transform from a tract of semi-forested rural land into one of the most interesting golf experiences folks describe after their first couple of rounds.

A 9-hole round at Kanawha Club generally takes the average golfer about an hour-and-a-half. Members have developed their own ways to enjoy Kanawha. We have three to four sets of tees on every hole, with yardages ranging from 55 to 240 yards. Twice a year, we convert the 9-hole layout into a 6-hole loop of cross-country golf. These events offer members a non-traditional approach to the game and a new way to enjoy our setup.

Kanawha Club started as an idea for a challenging private practice facility, spawned as a larger version of its owner’s urban backyard practice facility. The club takes its name from Kanawha County, set along the Kanawha River bisecting Charleston, W.Va. – the hometown of the owner and his wife. Ironically, the southern border of our property is the Little River, a manmade canal constructed in the 1800s that allowed bateau boats to circumnavigate the rapids of the James River toward their destinations upstream as part of the encompassing Kanawha Canal System.

Managing a par-3 course is an interesting endeavor. Overseeing the entire construction of a 55-acre parcel of land into a golf course with a few adjacent private residences was an interesting part of my first superintendent position. At 26 years old, I embarked on a mission that started as an idea and has grown into something I care very deeply about. It has continued to feed my passion for turfgrass management.

It’s difficult to understand daily life at a par-3 course. Kanawha has some extreme terrain and requires a different approach to what most turf managers experience, and it provides a unique approach to golf course maintenance and preparation. Due to the smaller size and minimal acreage, most duties on the course only take a fraction of the time to complete. Instead of mowing greens for the first few hours each morning, our jobs only take about an hour or so to complete.

It is not uncommon for some of our seven full-time staff members to complete six or seven different jobs on any given day. Because of this, a job board doesn’t make sense, as our list of tasks vary so frequently that we would spend more time updating and adjusting it rather than just allowing each day to dictate the revolving task list. Our staff members enjoy the variety. Their skills reflect knowledge and proficiency of every piece of equipment in our maintenance facility.

Perhaps the single most challenging aspect of managing a golf course for such a small membership is never losing sight of the expectations and standards of the Kanawha experience when there is a very real chance nobody besides staff members will pass through the gates. There aren’t many managers who can count the number of daily rounds on one hand or who can count the ball marks, divots and bunker shots of the prior day – and likely know who created them.

The minimal number of rounds means we generally have carte blanche as far as day-to-day operations. We rarely need to make accommodations for a full course, work backwards against play or fret over other headaches plaguing almost every other maintenance operation in existence. At Kanawha, maintenance has the luxury of being a priority.

Explore the April 2019 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show