I’ve seen it during the dozens of tree consults I have done over the years. The most emotionally demanding and time-consuming component of the job is managing golfers when it comes to trees.

Otherwise politically conservative business people suddenly turn into fanatical tree-hugging eco-terrorists. A stoic, self-contained introvert gets all weepy when talking about the memorial tree they planted for dear old auntie. And a 33-handicapper who spends half of his shots chipping back into the fairway from the woods worries that after removal of half a dozen trees the course will become “too easy.”

The first rule of thumb I advise greenkeepers is never to get into a discussion with a golfer about this or that tree without first having established some formal understanding of the proper role of trees on a golf course. Without that analytical framework, you are lost in a he said/he said dispute with no basis for an outcome.

Trees have a place in golf, one that must be balanced with the primary function of the site, which is the game of golf. That means the ability to grow quality turfgrass in a manner consistent with modern ecological and regulatory standards. That entails relying less than used to be the case on chemicals and more on standard natural cultural practices like sunlight, air movement and drainage.

To that end, there are six criteria by which trees on a golf course need to be evaluated as part of any tree management program.

Agronomics: You cannot grow turfgrass in a shadow box. Depending on the turf type, daily sunlight averages of anywhere from five to 10 hours are needed. Poa annua can thrive on the low side but bentgrass and Bermudagrass need more. Morning sun is most important, of course, but so, too, is air movement (wind). Since a golf course is open through many months of the year, it helps to pay attention to the sun angle during shoulder season and winter months, when light is lower and at a premium. Attention needs to be paid not only to tree canopies but also to roots — which often grow well into the greens and tees and can distort ground features as well as rob the ground of vital nutrients.

Strategy: There is no skill in chipping out sideways with a 4 iron. There is skill, however, in playing a full-bore recovery from rough beyond the fairway. The notion that tightly treed fairway corridors provide a test for golfers is based on a one-dimensional view of the game — as simply one of aerial power, a vertical form of bowling, if you will. Tightly-treed courses unduly favor strong players and make the game a sufferance for all other classes of golfers. The beauty of golf is having optional paths from tee to green, not requiring vertical golf down the middle.

Aesthetics: The eye naturally scans the horizon from left to right. When vertical obstacles intrude, there’s a sense of disruption and loss. A golf course needn’t be denuded for it to have an aesthetic appeal. The main thing is for the eye to be able to scan laterally under the canopy in order to perceive the full sense of the topography. There are two sorts of views to be had on a golf course: interior, across the site; and exterior, to the surrounding landscape. If both are unavailable, a lot is lost.

Health of trees: Most courses that are overstuffed with trees today were improperly planted randomly by green committees trying to fill space — often with non-native species that were fast growing. Many trees today are suffering, and often the ill-suited ones are crowding out the healthy, mature species that need to be highlighted. It helps to have an arborist assess the well-being of your trees — but remember that such a specialist is usually more concerned with preserving your trees than preserving your golf course.

Safety: This is probably the most overused excuse for planting trees, with laughable results and the creation of a secondary risk of blind ricochet that had not been anticipated. My experience is that about 80 percent of trees planed “for protection” don’t belong.

Budgets: Add up your actual tree budget, including inoculants, pruning, plus the extra labor required to pick up debris and leaves, as well as the cost of chemically treating those areas that are not in healthy growing environments. The true cost of trees at golf courses far exceeds most initial estimates and is worth having as a datum point.

I always feel a special empathy for superintendents whose clubs still have a “memorial tree-planting program” commemorated on a board in the clubhouse. The worst is when the donor gets to pick the species and the spot and then adds a plaque that needs to be maintained. The sooner these are phased out, the better.

Explaining all of this to golfers can be difficult. My advice is to avoid saying how exactly many trees are slated for removal. In most cases, a more accurate account would be the amount of caliper inches that would remain versus what’s on the cutting board – usually well over 90 percent when all is done.

It helps having a formal decision-making structure in place so that the superintendent has some assurances that he or she will be backed up once the call is made to keep or cut down a tree. Not, however, so much structure that every decision must be approved by a board. There needs to be some latitude in the process, so that the superintendent can decide about the fate of certain trees if they are obvious offenders in the category of “agronomics.”

The main thing is to have a program in place, plus an explanation for it. That will help dial down some of the emotional turmoil involved.

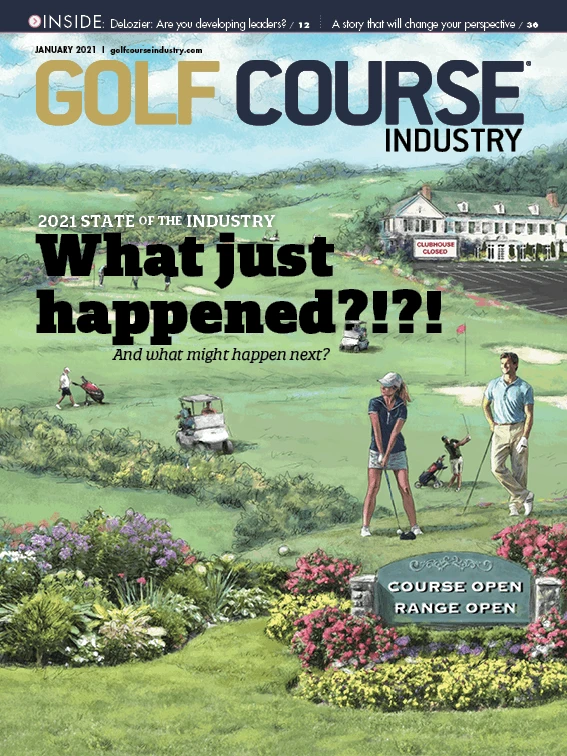

Explore the January 2021 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- USGA focuses on inclusion, sustainability in 2024

- Greens with Envy 65: Carolina on our mind

- Five Iron Golf expands into Minnesota

- Global sports group 54 invests in Turfgrass

- Hawaii's Mauna Kea Golf Course announces reopening

- Georgia GCSA honors superintendent of the year

- Reel Turf Techs: Alex Tessman

- Advanced Turf Solutions acquires Atlantic Golf and Turf