All golf courses, by root virtue, are instincted to grow forward.

Some very special courses, however, are just as much a living history of human existence.Since debuting in 2007, The Journey at Pechanga in Temecula, California, has fast proven a Southern California must-play, revered for its rolling topography, bubbling streams, elevated tee boxes and rustic routing through native land. And while designers Arthur Hills, Steve Forrest and team no doubt deserve ample backslaps for the modern architecture, The Journey’s path was ten millennia in the making.

Built upon the ancestral grounds of the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians, the property was where tribe members lived, survived, thrived and died, long before the thought of getting a 1.6-ounce dimpled sphere into a 4½-inch cup entered the concept of human leisure or livelihood.

Today, maintaining both the striking aesthetic of the course while concurrently — and continually — being well-abreast of cultural practices, is a balance that requires constant education and communication.

Such scales were evident from the outset of course design and ensuing construction, which had a back-and-forth of assessing routing amid ancestral grounds before a final design path was agreed upon.

“And then Steve (Forrest) finally looked up into the hills of the property and, asked, ‘What’s up there?’ almost in desperation,” recalls Gary DuBois, a tribe member and the director of Cultural Resources for the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians

At one stage in the survey, evidencing the verdant surrounds, Forrest got himself lost amid the native landscape. “He knew where he was,” laughs DuBois. “He just couldn’t find a trail to get back down.”

After ultimately agreeing upon routing, the tribe and designers moved ahead carefully. “One of the caveats in moving forward with the course was that our Cultural Resources Department would oversee development,” DuBois says. “So, we worked very closely with Steve Forrest and his crew. And, of course, we have many, many oaks on the property, which are sacred to the tribe, and, at first, the designers were tagging all these trees that were in fairway areas. And the fact remains the same today as it was then: We don’t cut down healthy oak trees. Period.”

Seen as an occasional course quirk to nascent players (e.g., the fairway-centered oak on the short, par-4 seventh), the oaks can’t be addressed by Journey maintenance staff unless first approved by Pechanga’s Cultural team.

“From the beginning, everybody, the whole crew, is on board,” says Mario Ramirez, head golf course superintendent at The Journey. “And if my guys see something being done (which shouldn’t be), or anything with the sacred oaks trees, they report it to me.”

Being “on-board” is not without preface or preamble. All employees at the course and the adjacent, eponymous Resort & Casino go through a learning process upon their hiring and are educated about the tribe’s history and heritage.

“You have to do your studying and ask questions. From the beginning here, everybody, all employees, go through training, and it’s all explained to us about what is sacred ground,” Ramirez says. “So, from the beginning, we’re very aware, and learn that if you don’t know or are unsure about something — you ask. We don’t make those mistakes. There’s a culture here, and everybody takes it very seriously.”

From the Cultural Department’s end, continually educating staff is in itself a challenge, though DuBois is fast to laud the communication chain he currently shares with Ramirez, who has been at The Journey for more than four years.

“Employees come and go, which means the institutional knowledge goes with them,” DuBois says. “So, when new people come in with their own idea how to run a golf course — and those may well be good ideas — we need to educate them on the cultural component and ensure they know the background. And we impress upon them: ‘Whatever you do, if you’re gonna dig or even if you’re going to trim back some braches, you need to give us a call first.’”

Ramirez adds that the tribe is understanding and versed on course needs, although every project needs approvals.

“We don’t just go ahead with digging holes anywhere, for, say, a drain,” Ramirez says. “We need to ask permission, and then the Cultural Center will come and inspect an area and either give us the green light to move ahead or disapprove it for the reasons behind the ground being sacred.”

Pechanga homage can be seen throughout the property via kiicha homes (meaning “home” in the tribal language) across peripheral areas, along with informational and educational signage located behind the fifth green.

The most sacred ground on course property can be found on both sides of the top-handicapped, par-5 ninth; along the right side, a lengthy, wrought iron fence runs in stark contrast to of the landing area, separating play from sacred grounds to which even tribe members aren’t allowed casual access.“On the ninth, the fencing protects the sacred ground all along the right side; none of us can go in there,” says Ramirez in earnest. “Nobody can, only with the tribe’s permission. And on the left side of the fairway on that same hole, those trees are also very sacred, and nobody can touch them.”

Noting that, back in the design and construction phase, the land upon the ninth was indeed the biggest area of concern before ultimate concession, DuBois says course staff is made especially aware of keeping golfers from going to find an errant ball beyond the gate.

“It is a bit of a choke point for the course,” DuBois says of a narrowed second shot, pinched between sacred areas. “It’s ceremonial ground (adjacent to the fairway), and some of the elders who are no longer with us, they consulted on that, and there was a big compromise in creating that hole.”

Buoyed by the dramatic topography, there is a genuine mysticism to the course.

“In certain places … golfers won’t play on them, walk over them or even see them, but there are burials out there; and we try to be low-key about those areas,” DuBois says. “Some people have said they feel an ‘otherworldliness’ on this property; that there’s something here.”

By paying homage to the history of the Pechanga people, Journey staff and modern-day tribe leaders — akin to the land’s indigenous ancestors — maintain a unique adoration for the land, bestowing respect to the grounds’ sustainability via environmentally-friendly practices.

“When we say this golf course is 10,000 years in the making, it’s true,” DuBois says. “Because, wherever Pechanga people lived in the pre-contact history, if there are sites to that effect on the golf course — we didn’t build on it. We believe this is one of, if not the most culturally-sensitive golf course in the country.”

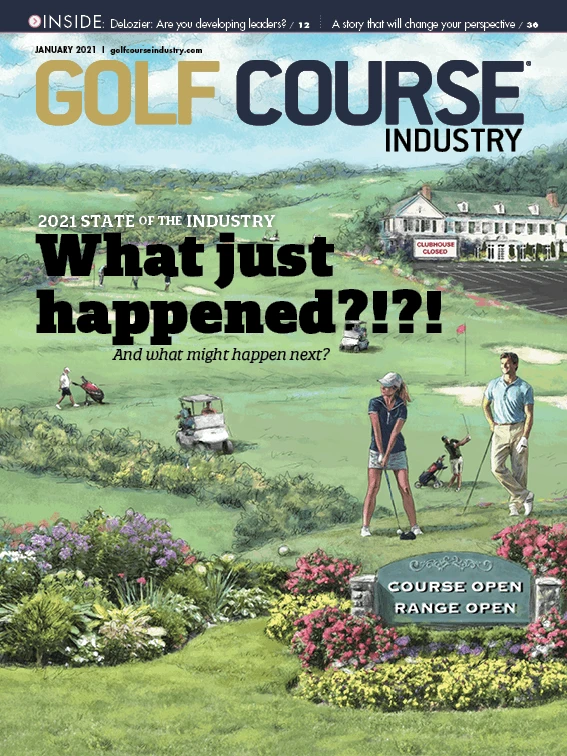

Explore the January 2021 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show