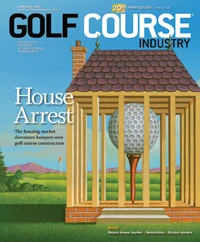

You’ve read about it in newspapers. You’ve heard about it on TV. And you even might be in the thick of it. It’s the housing market. And yes, it’s in a slump.

While some say it’s a reflection of the overall economy, all agree it’s part of a downward cycle that will improve eventually. When that turnaround begins or when this cycle bottoms out, nobody knows for sure. But one thing is certain: The poor housing market has affected the overall golf course industry negatively.

The impact on the golf market is noticeable because builders and developers have seen the number of new projects steadily decline since January 2007, says Henry DeLozier, v.p. of golf for Pulte Homes. About 100 new golf course projects opened in 2007, and that number will be down decidedly in 2008, DeLozier says.

“Many builders are changing the timing of their projects to coincide with the resurgence of the housing market,” he says. “There are some projects being put on hold amid development. If one starts a projects then stops it, efficiency is lost and additional costs increase because the builder has to remobilize. The vibrancy of market and cost of capital are two good reasons to stop building.”

Almost everyone in the golf industry is affected by the housing market because everyone plans on new projects rolling out, DeLozier says.

“One in five of our projects have a golf course in it,” he says. “Most of the projects include golf as a lifestyle. The housing market drives all golf at Pulte. We don’t build free-standing golf courses.”

Like all of the big home builders, Pulte Homes projected a slow 2007, but most builders have found the downturn to be deeper and more prolonged than expected, DeLozier says. However, few projects get scrapped altogether because entitlements are set and deeds are tied to a master plan. Once builders start a development, they see it to fruition. An exception is if a project is undercapitalized.

Architects see the housing downturn affect golf course construction through their project lists. Six of Arthur Hills/Steve Forrest & Associates projects are under construction (three in the U.S. and three international), and 26 projects are on hold because of financing, owner decision-making, permitting and government regulations, says Steve Forrest, the firm’s principal and president of the ASGCA.

“The housing downturn has delayed projects,” says Forrest, adding that about half of the firm’s 26 projects are tied to residential home building. “Things won’t improve until late 2008 or 2009. The bigger domestic golf course builders – Landscapes Unlimited, Wadsworth Construction, Heritage Links – are looking overseas.”

The majority of Weitz Golf International’s volume and revenue is through clubhouse construction, says Oscar Rodriguez, v.p., construction manager. On one project, Magnolia Landing in Fort Myers, Fla., Weitz finished its job, and the developer shut it down. The course is expected to close, Rodriguez says.

Also, Weitz was working on the foundation of a clubhouse on another project in Fort Myers called Portico, and that project was shut down, and Weitz pulled off the job. However, Rodriguez says he’s not sure if the golf course at Portico will be shut down. Homebuilding started at Magnolia and Portico but now has stopped because of poor sales, he says.

“Because the developer side of construction has completely stopped, we need to focus on the private side of clubhouse renovation,” Rodriguez says.

It’s a cycle

Rodriguez experienced a similar downturn during the early 1990s while with Fairway Construction, which has since been incorporated into Weitz Golf International.

“I feel like early ’90s was just the golf course industry pre-Tiger Woods,” he says. “This time around, it feels like the downturn is because of the U.S. economy with the weak dollar. California and Florida were attracting many foreign investors who wanted to take advantage of the weak dollar. The downturn is more U.S. based than I thought in the early ’90s, which was more golf industry based. We don’t officially have a recession, but most people feel one is coming.”

Because now there’s more of a need to be bonded than before, Rodriguez doesn’t see how smaller contractors can put all of their bond capabilities into one project. Contractors need to include more renovations in their scope of work because they operate more smoothly and new construction projects can be put on hold financially at any time, he says.

“This year will be a trying year,” he says. “For example, smaller architects or subcontractors might not have enough work. It will be interesting to see who will withstand the downturn.”

For Forrest, it seems like there’s a downturn every 10 years, although Sept. 11 was a different market factor.

“We went through a period of strong renovation from 2003 through 2005, then back up to new projects in ’05 through ’07, then it fell off,” he says. “And builders are lagging behind architects a couple years based on the development process. Right now, builders are getting the perfect storm.”

DeLozier saw softness in the market like this in the early to mid-90s and in 1987 and 1988. The housing cycles, which follow other economic patterns, are hard to predict, but they’re a certainty. As such, Pulte is prepared.

“Pulte has a great deal of experience,” DeLozier says. “We have a seasoned senior management team that manages well through the housing sector. The company has downsized as it relates to market conditions.”

The early 1990s was the last downturn in the golf industry, but there were various components involved, says Dave Richey, senior v.p. of the country club division of Toll Brothers.

“I don’t know how long this downcycle will last, but the basic demand for home building is still fairly strong – there’s 1.5 million to 1.7 million new homes built each year,” he says. “Golf course development is totally driven by homes. Where golf courses are, they represent our largest communities. We wouldn’t have a community with a 1,000 homes without a golf course.”

Toll Brothers, which has 300 residential developments throughout the country, typically turns a golf course it develops over to members or a third party. And the reasons to build them vary.

“It’s based on amenities or the number of homes in a community,” Richey says. “Permitting requires them to be built. Sometimes a golf course is added to a development to get rid of wastewater.”

Toll Brothers was working on a project in Naples, Fla., that was delayed further because the developer is reluctant to start right now.

“Even though things have slowed down, we’re still looking for country club neighborhoods three to five years out,” Richey says. “Land prices are declining, making large land tracts attractive. We’re in the permitting and planning process.”

Hit hard

Superintendents will feel the ripple effect of the housing downturn because there are fewer new golf courses, which in turn, means fewer jobs, more severe competition for employment and less mobility for a superintendent looking to leave a job, DeLozier says.

Trevor Brinkmeyer is one superintendent who has felt the effects of the slumping housing market. Brinkmeyer, who’s an interim assistant superintendent at Quail West Golf & Country Club in Naples, Fla., and is looking for a full-time superintendent job, used to work at the private 54-hole Shadow Wood Country

Club in Bonita Springs, Fla. He was a superintendent there for five years and started out managing one 18-hole golf course. When one of the other two superintendents left, he oversaw two golf courses while the other superintendent oversaw the third 18-hole course.

Bonita Bay Group, a developer, owns and operates Shadow Wood. It’s primary objective is to sell property and use golf courses as an attraction, says Brinkmeyer, who estimates Bonita Bay Group’s portfolio includes 11 golf courses in five communities.

Shadow Wood, which has 1,050 members and generates about 40,000 rounds annually per course, sold out in 2006 but originally wasn’t supposed to sell out until 2012, Brinkmeyer says. Bonita Bay Group wanted to turn club ownership over to the members in 2007, but the members and Bonita Bay couldn’t agree, so Bonita Bay held on to it, Brinkmeyer says. Things were humming along nicely for a few years, but ultimately Bonita Bay laid off 30 employees in March of 2007, Brinkmeyer says.

“I didn’t think much of it at the time because we were productive and watched our spending,” he says “But Kenyon Kyle, the former director of golf who I was reporting to, was more worried because he was in a management position and knew more of what was going on. There were no more talks of layoffs for a while, then three people were cut. Through the summer, it was like any other, but in August, I found out I was one of the cuts. It was immediate.

“Bonita Bay wasn’t selling as many homes and had to make cuts,” he adds. “The real estate market boomed, then crashed. Bonita Bay was sitting on land and had to pay the bank, so it cut labor, which is its biggest expense.”

Brinkmeyer is job hunting in Georgia, Florida, Texas and the Carolinas.

“I have an opportunity in Mexico, but it hasn’t developed as quickly as I thought,” he says. “It’s a different situation when you have financial obligations.”

International flavor

But the housing market’s condition doesn’t mean doom and gloom for all. There are positives of the downturn, Forrest says.

“We stepped up the effort to work internationally, including China and the Middle East,” he says. “Once you’re there, you get some momentum. It’s a snowball effect. The nice thing is you have access to the best golf course sites that you didn’t have the opportunity to access in the U.S., such as coastal sites in Turkey on the Black Sea.”

Hills/Forrest’s international work started during the downturn in 2001, and the recent housing downturn has reinforced the firm’s decision to acquire more work overseas, Forrest says.

“It takes a while to get established overseas – it takes more leg work,” he says. “But the scarcity of qualified golf course builders overseas makes the U.S. expertise very marketable. Golf and houses is a new concept internationally, where traditionally golf courses are stand-alone. We keep scratching and clawing out there and have been able to maintain our staff of 11. You can survive.”

Down the road

Eventually, the housing market will improve. For example, many homes are being sold in high-tech areas and to people coming into the country, Richey says. Demand for country club communities will continue but not like 10 years ago.

“From our experience, people aren’t buying into country club communities for the golf alone,” he says. “We’re seeing decisions to live in country club communities driven by the value of the home, security, fitness, swimming and athletics. Food and beverage isn’t as big a driving factor. Golf is a million-dollar view, and only 50 percent of those living on a golf course actively golf.”

Yet, the industry needs to build shorter golf courses, Richey says.

“We’re aiming for double-digit handicappers,” he says. “We want them to have a good time and a quick round. We see a decrease in the number of rounds per member but that doesn’t mean the desire to play golf is declining. Time is an issue.”

Forrest doesn’t think the premium on lots next to golf courses will ever decline because they provide recreation and beauty for the homeowner and profit for the developer.

“Golf and houses are forever married,” he says. GCI

Explore the January 2008 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Golf Construction Conversations: Stephen Hope

- EnP welcomes new sales manager

- DLF opening centers in Oregon, Ontario

- Buffalo Turbine unveils battery-powered debris blower

- Beyond the Page 66: Keep looking up

- SePRO hires new technical specialist

- Plant Fitness adds Florida partner

- LOKSAND opens North American office