There are 3,676 9-hole golf facilities in the United States, according to the National Golf Foundation. Scattered among all 50 states, each 9-holer provides respites and joy to millions of small-town, mega-city and suburban golfers. Eighty-five percent of 9-holers are open to the public. Doug Myslinski, a golf construction and design devotee employed by Wadsworth Golf Construction Company, considers courses of this ilk “the heartbeat of what golf is and how we can grow it.”

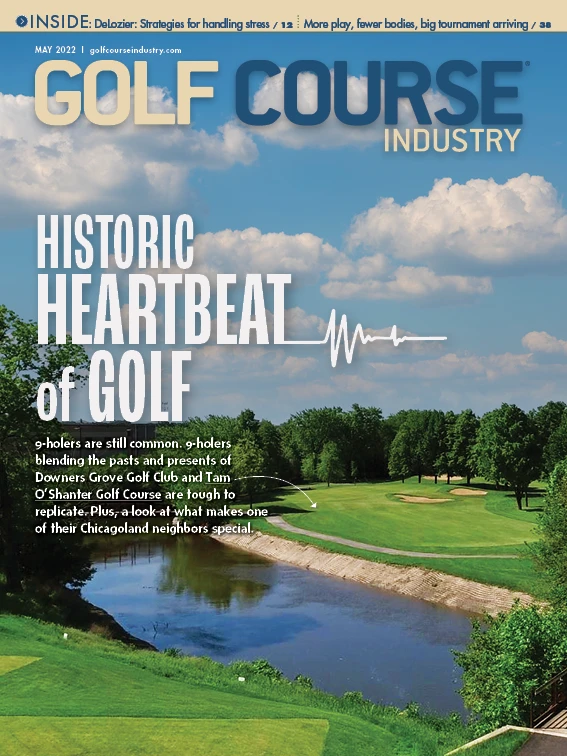

Myslinski lives in the sprawling Chicagoland region, an inland golf mecca supporting an abundance of 9s, 18s, 27s, 36s and gargantuans. Within every golf subset, a few courses possessing incomparable pasts demonstrate modern vitality. Downers Grove Golf Club and Tam O’Shanter Golf Course operate in this subset.

Downers Grove and Tam O’Shanter are municipal facilities occupying contrasting Chicagoland tracts. Owned and operated by the Downers Grove Park District, Downers Grove Golf Club is a hilly site in a prosperous southwest suburb. Owned and operated by the Niles Park District, Tam O’Shanter is a relatively flat northwest suburban course flanked by dense industrial, commercial, residential and Forest Preserve District of Cook County plots.

Commonalities exist between the courses. For starters, they are both 9-holers in heavily populated areas. They are also affordable and accessible. An ambitious golfer who relishes walking can play one and then make the 27-mile trek to play the other on a weekday and drop less than $45 in green fees. Whether one walks Downers Grove or Tam O’Shanter, or both, they are experiencing land that changed golf.

Charles Blair Macdonald, the patriarch of Chicago and American golf, designed the original Chicago Golf Club in 1892 and 1893 on the current site of Downers Grove. Chicago Golf Club moved to its Wheaton location in 1895, the same year its original course was renamed Belmont Country Club and reverted to nine holes. The Downers Grove Park District purchased and renamed the course in 1968.

Have you watched televised golf lately? Then, you already have a connection to Tam O’Shanter. In 1953, Chicago businessman and golf promoter George S. May televised the annual World Championship of Golf conducted at his Tam O’Shanter Country Club. Nobody had attempted to put golf on television before May. The event featured a $75,000 purse and May invited players from six continents to Niles Township. The tournament had a made-for-TV ending as Lew Worsham holed a wedge on the final hole to topple Chandler Harper by a shot. May died in 1962 and Tam O’Shanter faded as a prestigious private club after hosting the Western Open from 1964 to ’65. Howard Street intersected the 18-hole layout and the Niles Park District purchased 37.5 acres on the south side of the street for $1.33 million. Tam O’Shanter reopened as a nine-hole course in 1972.

Modern golfers are immediately made aware of each course’s past. A sign adjacent to Downers Grove’s first tee includes a three-paragraph description of the course’s development. The final line: Therefore, in 1893, the first eighteen-hole golf course in the United States was established on this site. A billboard-sized sign behind Tam O’Shanter’s first tee box lists winners of prominent men’s, women’s and amateur tournaments above a five-paragraph course history.

Downers Grove and Tam O’Shanter combined to host more than 80,000 rounds in 2021 despite cold-weather climates. Superintendents Jeff Pozen and Jim Stoneberg are damn proud of where they work and the recreational value their workplaces provide. They are bullish on the present and future of the 9-holers their small teams maintain.

“Great pieces of land that turn into great golf courses are just timeless,” says Pozen, Downers Grove’s superintendent for the past 17 years. “They are going to last forever. There’s something about them.”

Stoneberg, a former sports field and park grounds manager who became Tam O’Shanter superintendent in 2000, adds, “Hopefully this is nothing but still a gold mine for the park district. I hope it continues the way it is, whether it’s the number of rounds or maintenance. It’s a staple in this town.”

Suburbanization meets early

American golf on Downer’s Grove seventh hole.

Condos and an auto dealership parallel the par 4. A community recreational center lurks behind the green. Tees are tucked into a wooded corner of the property, the landing area is slightly raised, the approach steep, and the green severely sloped from back to front. One fairway bunker is detached from the right side of the fairway. The hole, according to Pozen and general manager Ken McCormick, is the closest to its original Macdonald form on the course, making it the most accessible and affordable Macdonald-designed hole in the world. Nearly the entire Macdonald design portfolio consists of ultra-exclusive private clubs.

The allure of Downers Grove’s landforms attracted Pozen to his current job. Pozen walked the course for the first time as a 15-year-old playing high school golf in 1986. “I barely remembered most of the course,” he says, “but I remembered the seventh hole for sure. That green was crazy. People were putting off it. Once I came here to start working 17 years ago, you think, ‘This is not how I remembered it.’ I didn’t grasp what it was back then.”

Now, Pozen, who read Macdonald’s 1928 book “Scotland’s Gift: Golf” when he was in high school, protects Macdonald’s work, ensures the seventh green doesn’t become too fast and cultivates pleasant conditions for golfers beginning rounds at 5:40 a.m. and well after 5:40 p.m. He juggles it all with one full-time co-worker and four seasonal employees. The peak-season team is rarely at Downers Grove on the same days. Pozen staggers his limited labor resources. Mondays resemble Saturdays, Tuesdays mirror Sundays. “Every day is pretty much like a weekend day here,” he says. “There’s really not a slow day.”

Downers Grove supported 44,717 rounds last year. Some golfers care deeply about the history; others have no idea the course played a prominent role in American golf development. On a gloomy and chilly March evening, as Pozen and McCormick are showing a visitor black-and-white routings and articles inside the clubhouse, children are gathered inside a heated, 10-bay shelter constructed in 2018 to support more cold-weather activity and programming. The shelter is part of a driving range complex added in 1992, when the Downers Grove Park District commissioned a redesign of the course. The projects and dates above indicate the evolution of Downers Grove. Not everything from the 1890s resonates with modern golfers. The scene outside the clubhouse on the March evening also indicates that even Chicagoland’s youngest golfers are a hardy lot.

Five green pads, according to Pozen, remain from Macdonald’s design. Greens averaged around 4,000 square feet when Pozen arrived. Through his restorative work, putting surfaces now average around 5,000 square feet. Pozen also has restored several bunkers on Nos. 3 and 6, and portions of the par-3 fourth and eighth holes. Aerial photos from the 1930s and discoveries unearthed below playing surfaces guide the restorative work, which occurs in what Pozen calls “the late, late fall,” because play doesn’t recede until winter weather arrives.

“The surge in play has made it challenging,” Pozen says. “Usually, in November, we get room to work. But it’s been warm the last couple of falls.”

Abundant October and November play is unlikely something Macdonald envisioned. “When it’s warm in the fall, we’re packed,” McCormick says. “Then the days where there’s no play, you can’t go out there and work because weather conditions don’t allow it.”

Downers Grove doesn’t have an official beginning and ending to the golf season. If it gets warm enough for winter golf, customers fill the course and range. Golfers notice — and appreciate — courses changes upon returning from weather-induced breaks. Pozen and McCormick receive autonomy to decide how to best enhance Downers Grove within the annual budget. Time, money and available labor limit creativity more than any board, committee and owner.

“We do what we can and that’s why things have happened pretty slowly,” Pozen says. “I have done a few greens, but I haven’t done greens in a couple of years, so I have switched over to bunkers. We are slowly getting there.”

Improvements extend beyond playing surfaces. Pozen’s team also has recently expanded the range to add an instructional tee and guided the effort to secure an Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary Program for Golf certification. That willingness to enhance and adapt could keep Downers Grove around for another 130 years.

“The idea of nine holes in a premium setting has its niche and that allows the course to have a long lifetime,” McCormick says. “Prior to the pandemic, golf was in a tough spot in a lot of places. But this was set up to do well even then. Going forward, there’s a bright future for this property.”

Too many floods over more than two decades. Stoneberg loses track of how many times the North Branch of the Chicago River has overwhelmed Tam O’Shanter’s turf during his tenure. The river promotes serenity, factors into course strategy, and protects businesses and homes from excess stormwater.

“It serves the purposes golf has for hundreds of years and that’s the conveyance of water,” Myslinski says. “It’s a high-density area and this course prevents a lot of houses and businesses from receiving water. But it takes its toll on the course.”

Stoneberg is inundated with soggy — and even smelly — stories. Take 2005, for example, when remnants of Hurricane Katrina reached northern Illinois.

“Water was flowing over Howard Street,” says Stoneberg, pointing to the busy road 30 feet behind his office. We lost seven acres of turf, we hauled out over eight semis of sludge. It was like a 100-year flood. It had dumped all the crap that was on the banks for years onto the golf course. But we were only closed for about seven days. We opened on that dead turf. I was able to get out and aerate it. I still can’t believe just the smell and everything. Who would even want to be out there?”

The question is rhetorical. Private clubs surround Tam O’Shanter, so being the most accessible course in the neighborhood means achieving valiant feats to keep history open. Tam O’Shanter, unlike Downers Grove, closes in the winter. When the season begins, usually in late March or early April, golfers play the course in any weather. For most of his tenure, Stoneberg was the lone full-time employee. He received his first year-round co-worker last year, as his rotator cuff ached more and more from a career spent working outdoors. Stoneberg receives seasonal help, although it has become increasingly tougher to fill positions.

The number of significant rain events (translation: floods) are also increasingly more common, according to Stoneberg. “Here, in the last five years,” Stoneberg says, “we have had two years with 12 to 16 events, which is unheard of. We lost a lot of revenue.”

Tam O’Shanter opened in 1925 and flooding represents part of its history. Tam O’Shanter has its own museum and the collection includes a black-and-white photo of May staring out a clubhouse window at a course overwhelmed by raging water. The Niles Park District made a big move to mitigate effects of flooding when it engaged Myslinski and Todd Quitno of Lohman Quitno Golf Course Architects to create a master plan.

“Ninety percent of our goals were to get the tees in the floodplain out of the floodplain,” Quitno says, “and then get drainage into areas so the golf course could recover quickly after floods. This course is in a floodplain. It always will be in a floodplain and has suffered a lot over the years from flooding damage.”

Work commenced in late 2017 and concluded in mid-2018. The project was the first significant renovation since the Niles Park District purchased the course. Not only were tees rebuilt and drainage added, 22 bunkers were constructed using aggregate liners and low-mow bluegrass green surrounds were added. “I still don’t believe it ever happened,” Stoneberg says of the project.

More open days means more opportunities for golfers to appreciate Tam O’Shanter’s place in golf history. The sixth hole, a par 3 playing over the river, is the closest current hole to the layout touring pros experienced. Byron Nelson, Sam Snead, Ben Hogan, Babe Didrikson Zaharias, Louise Suggs and Patty Berg won at Tam O’Shanter, and May used the club and tournaments to entertain business partners.

“It takes my breath away when I look at some of the old tapes. They took a helicopter and played each hole with a pro just so George May could show off his course,” Stoneberg says. “All of the big names played here. It’s a shame that it’s not here anymore in that form. But I don’t think I’d be running the course if it was a championship course.”

Stoneberg recently found an old Toro magazine advertisement featuring former Tam O’Shanter superintendent Ray Didier alongside Nelson, Snead, Hogan and two turf peers. Didier prepared the original course for numerous tournaments with the trio in the field. “I would have loved to walk the course back then,” Stoneberg says.

The course Stoneberg maintains measures 2,440 yards from the back tees and the clientele possess a different skillset than American golf’s first “Big Three.” But Tam O’Shanter remains relevant … and moves water better.

“You can see that just by the tee sheet,” Stoneberg says.

Explore the May 2022 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show