Forget golf.

The panorama on a small tee atop a lava rock mound snugged between Nanea Golf Club’s eighth green and ninth tee might not exist elsewhere in the world.

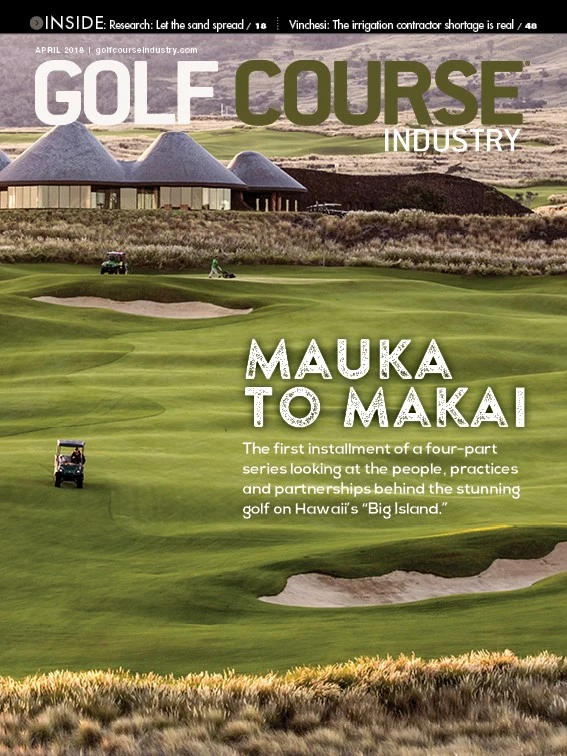

Instincts point the body east, facing a meandering par-4 with a view of a modest clubhouse boasting five copper roofs signifying volcanic vents, landscapes natives call pu’u. Mauna Kea, a snow-covered 13,796-foot mountain, towers in the same direction.

Rotating clockwise, the body shifts south to an expansive lava rock field covered with yellowish fountain grass. “You’ll turn the corner,” director of golf course maintenance Scott Main says, “and you swear there should be a giraffe or something like that sitting there. It’s like a savanna.”

The westward view suggests whales instead of giraffes. Along with a Pacific Ocean backdrop, comes a glimpse of Four Seasons Resort Hualalai, where Dan Husek sees gigantic mammals when performing his job. “When you go out to 17 tee and look at some sea turtles up on shore and look out along that shelf where the ocean gets deep and a whale is jumping … Yeah, it’s pretty special,” says Husek, who oversees the maintenance of the resort’s 36 holes.

One more view exists from the nearly 100-foot lava mound: the island of Maui sits to the north.

A splendid and diverse landscape attracts golfers to Hawaii’s “Big Island,” home to 18 facilities, including Nanea and Four Seasons Resort Hualalai. The people responsible for turning tricky terrain – ever try chiseling through blue rock to check an irrigation leak? – are even more fascinating than the landscape.

A crew such as the 24-worker outfit at Nanea can include Hawaiians, Filipinos, Samoans and Tongans. Watching the groups work together to produce elite conditions inspires supervisors, most of whom hail from the mainland.

The Big Island, population 196,248, is viewed as a dreamy place to live and work – until you actually try establishing a life on it. Once a temporary stay becomes permanent, the reality associated with life on an island emerges. Family and friends are one, two and sometimes three plane rides away, and numerous mainland management philosophies become obsolete. Golf course maintenance on the Big Island, the largest of Hawaii’s eight islands, doesn’t resemble what industry professionals experience on the mainland.

“You can’t come in with a bull-nosed type of attitude where you are going to conquer and be this hero or whatever,” says Josh Silliman, the director of golf at Mauna Kea Resort. “You really have to come in and embrace what these people are, and you have to learn how different it is.”

Or, as Main says, “You’re not going to change people. You have to adapt to the culture and accept a change. It’s more about seeing their way of life.”

What works in Boston, Philadelphia or Chicago is unlikely to yield the same result in Kailua-Kona, the epicenter of the Big Island’s high-end golf scene. “Aloha,” an upbeat and welcoming spirit, permeates all aspects of life and work, including golf course maintenance.

Instead of immediately scurrying to assignments, mornings often begin with conversations about family activities or recreational pursuits. Telling employees to hustle at 6 a.m. can isolate a manager.

For all its tourist glitz, Kailua-Kona remains a rural place, thus the more casual pace, says Kohanaiki agronomy manager Joey Przygodzinski. Born in Kona Hospital and raised in South Kona, Przygodzinski is a Big Island native leading a 70-worker department responsible for maintaining an 18-hole golf course; common and home landscape areas; more than 200 anchialine ponds; a public and private beach park; and community garden. A key part of his job involves training mainland-educated managers to embrace interactions with co-workers. Reaching a Hawaiian worker, Przygodzinski says, requires a personal approach.

“I always try to get in the trenches with my team,” he adds. “If I train you to do something or tell you to do something, I know how to do it myself. I kind of focus my other managers on the importance of training and getting that training done on a personal level vs. verbal.”

Aloha goes many ways. Pulling into the gate at a private club can lead to a 10-minute conversation with the attendant. And it’s not uncommon for club members to ask crew members about their lives or flash the shaka sign to employees. Created by extending the thumb and little finger, the shaka symbolizes a friendly gesture. Managers are also known to give the shaka to employees. Elaborate handshakes followed by hugs are signs of deeper friendships.

Asking employees to work 10- or 11-hour days to enhance turf can further isolate a manager. Living on the Big Island isn’t cheap – gas cost nearly $4 a gallon and a dozen eggs exceeded $5 in mid-March – but beaches, trails, mountains, waves and, most important, remaining close to family make financial hardships worthwhile for natives. Most Hawaiians, in other words, work to live. A 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. workday makes the Hawaiian dream possible. “The hours are great,” says Chance Lincoln, a Big Island native who started working at Four Seasons Resort Hualalai in the mid-1990s. “We get off early and you can still do things at home. Most of the younger guys leave here and surf.”

Requiring employees to wear pants? Good luck finding a crew.

Don’t be fooled by the laidback vibe, though. Golf course maintenance represents a serious profession on the Big Island. Visitors don’t want to play on patchy turf or dirt-filled bunkers, and they are willing to pay exorbitant prices for quality conditions. The maintenance budgets of elite courses are 20 to 30 percent higher than comparable mainland facilities, according to multiple superintendents and industry representatives. Golf represents major commerce on island.

“This industry is a big part of the community because the service industry is a big deal out here,” Kohanaiki superintendent Luke Bennett says. “You will find that there are two types of people on the island: there are people who work in the service industry in the morning and there are people who work in the service industry at night.”

A Colorado native who has worked at multiple courses in his home state and California, Bennett arrived at Kohanaiki in 2015. His grandmother died a decade ago before fulfilling her dream of visiting Hawaii. When the Kohanaiki job opened, Bennett grappled between mainland security and Big Island curiosity. His grandmother’s ambition factored into the decision. “It was something that she never had a chance to do and something that I took to heart when I had the opportunity,” he says. “It would have been a very easy situation for me to say, ‘No, I’m going to pass.’”

Bennett encountered a culture and growing environment unlike anything he had experience. The 4,028-square mile island, which is bigger than Rhode Island and Delaware combined but smaller than Connecticut, supports four of the world’s five major climate zones: tropical, dry, temperate and polar. Anywhere from eight to 11 subclimates, depending on the climatology source, exist within those four major climate zones,

Kohanaiki’s coastal location places it in a tropical zone, making it warm enough for turf to grow every day. “I can’t tell you how many days a year we take off mowing the greens,” Bennett says, “but it can probably be counted on two hands.” Fast-growing turf requiring daily mowing assignments and placing extreme wear on equipment is on the lengthy list of agronomic challenges.

Water quality varies by facility. Nanea has a well, providing the club with what Main describes as “fairly decent water.” Four Seasons Resort Hualalai receives deep well water. The water then goes into a reverse osmosis (RO) plant. The hotel and homeowners receive the treated water while the rejected water enters the golf course irrigation lakes where it combines with well water, creating a salt-infested blend. “I don’t think using RO concentrate is common anywhere in the world,” Husek says. “Maybe there’s another place that’s using it. But I don’t know of it.”

At least Four Seasons Resort Hualalai has a uniform water source. Kona Country Club irrigates its front nine with effluent water and back nine with well water. Salinity levels on the back nine are significantly higher than front nine, says superintendent Derrick Watts. “You have almost two golf courses here,” he adds, “and to be able to maintain that is interesting and fun.”

Opened in 1966, before Hawaii implemented ultra-rigid environmental permitting policies, Kona Country Club features holes hugging the Pacific Ocean, including the par-4 12th which plays over a blowhole. The layout makes Watts one of the few superintendents concerned about waves washing lava rock over turf and causing tip burn to Bermudagrass.

Lava rock is wonderful for aesthetics, but it’s not ideal for holding nutrients. Blue rock, the layer below the lava rock, is even worse. “It’s difficult to get down to the root zone and to go as deep as you want to go,” Watts says. Longtime Kona Country Club employees have dozens of stories about breaking aerification tines.

Winds range from tranquil to violent. Mauna Kea Resort, a 36-hole facility near the island’s north tip, can receive trade winds reaching 70 miles per hour, making replenishing bunker sand a routine assignment. Other facilities might experience weeks without a breeze exceeding 10 miles per hour.

The Big Island might be the only place where courses within a 20-mile radius successfully maintain bentgrass, Bermudagrass and paspalum greens. Nanea, a David McLay Kidd design opened in 2003, is one of the first courses in North America to install paspalum on every playing surface. Neighboring Four Seasons Resort Hualalai supports Bermudagrass surfaces. Nanea battles dollar spot; Four Seasons Resort Hualalai encounters Bermudagrass decline and mini ring.

Contrasting turfgrass landscapes and turfgrass varieties are important parts of the Big Island golf experience. The most endearing aspect – and the key to a manager and visitor achieving a greater understanding – involves the people living and working on the land. “Anybody can come to Hawaii and see Hawaii from the outside in,” Lincoln says. “But you have to know Hawaii from the inside out.”

Guy Cipriano is GCI’s senior editor.

Explore the April 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show