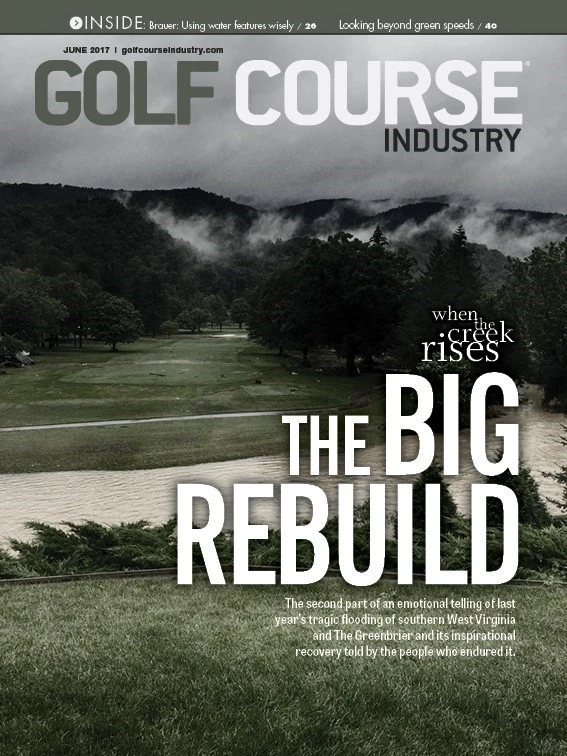

“It didn’t even look like a golf course anymore. People’s personal belongings, cars … you could barely see the tops of cars. It was filled with rock and gravel. Just seeing everybody’s personal property down there was something you couldn’t believe unless you saw it.” —Roy Young

Cars, boulders, refrigerators.

There’s no template for how to begin life after a natural disaster, and sleep doesn’t come easy when a normal period becomes numbing. So, Josh Pope, Chris Anderson and Drew Greene started the morning of June 24, 2016 the same way as thousands of others trained to maintain turf. They headed straight to the golf course.

The saunter from The Greenbrier’s stately white hotel to its golf clubhouse should be soothing. A springhouse once believed to possess healing powers sits between the structures. Without the rejuvenating waters, it’s unlikely southern West Virginia develops into a gathering spot for well-heeled residents from surrounding states.

Resorts, above all else, are therapeutic places. And golf, when played with the proper mindset, is a therapeutic game. Pope, Anderson and Greene landed in White Sulphur Springs, W.Va., because of the intertwined relationship. Golf has represented a major part of The Greenbrier’s mission since renowned architect C.B. Macdonald and talented associate Seth Raynor designed a course on its grounds in 1913. The resort needs people trained in the art and science of golf course maintenance to protect Macdonald and Raynor’s work. Pope, Anderson and Greene – a superintendent, assistant superintendent and turfgrass intern – are here on this eerie morning, hundreds of miles from their respective hometowns, because they grasp concepts such as labor efficiency, pest control and evapotranspiration rates.

Immediate history trumped distant events as they walked past the springhouse, which they couldn’t see anyway because of darkness. An event meteorologists later declare a “1,000-year flood,” slammed the region, forcing them to spend the night in the hotel. Nobody slept well, a trend over the ensuing months. Despite the darkness, they decided to hover outdoors instead of inside a hotel room.

“You don’t’ know where to start. It was a shock. It’s overwhelming. That’s what it was. With the golf courses, you don’t know where to begin.” —Randy Bittinger

The trio encountered thick fog, yet surprisingly little water when they reached a paved area between the clubhouse and Howard’s Creek, which rose from its banks a day earlier. “All three of us probably didn’t sleep well that night,” Anderson says. “We all woke up at 5 a.m., probably even earlier. It was really foggy and you couldn’t really see. But when we got down to the water, it was pretty much gone at that point.”

Instincts reigned when sunlight arrived. Pope began inspecting the condition of The Old White TPC, a famed course designed by Macdonald and Raynor scheduled to host the PGA Tour’s Greenbrier Classic in 13 days. The tranced superintendent was staring at destruction. “The question I kept asking: ‘What just happened.’”

Pope continued walking the course. On the second hole, he found a dog he later learned was owned by a co-worker’s wife. On the ninth tee, he spotted a cart used by PGA Tour representatives evacuated from the course the previous day. With the dog by his side and the cart somehow operating, he meandered navigable portions of the course, passing objects he never imagined seeing on a golf course. Co-workers experienced their own surreal moments upon seeing the post-flood version of The Greenbrier’s golf courses for the first time. Ten inches of rain on June 23, 2016 changed the next year of their careers.

Propane tanks, bridges, mattresses

The Greenbrier Classic provides an athletic and economic bonanza for West Virginia. Introduced in 2010, the tournament’s short history includes a round of 59, spectators receiving $100 bills from a billionaire following holes-in-one, and appearances by golf stars Tiger Woods, Phil Mickelson and John Daly. Organizers planned a rip-roaring celebration for 2016, with free weekly grounds badges for spectators, a celebrity pro-am featuring Denny Hamlin, Danica Patrick, Larry Fitzgerald, Shaquille O’Neal and Nick Saban, and youth clinic conducted by affable golf professional emeritus Lee Trevino.

CBS broadcasts the final two rounds, leaving thousands of viewers fascinated by The Greenbrier and West Virginia. The satisfaction of showcasing their delightful surroundings outweighs the strain it places on an agronomic team responsible for maintaining three 18-hole golf courses. “We want to put on a good show,” says Kelly Shumate, the resort’s director of golf course maintenance since 2010.

All decisions involving The Greenbrier Classic are calculated, and resort officials close The Old White TPC 10 days before the event. The stakes aren’t just high for professional golfers. The upscale resort segment of the golf industry is crowded, competitive and cutthroat. Presenting a gleaming course on worldwide television boosts business.

No business means more to southern West Virginia than tourism, which generated $243.7 million in direct spending in Greenbrier County, according to a 2012 “Economic Impact of Travel on West Virginia” report prepared by Dean Runyan Associates. The Greenbrier employs close to 2,000 people during its peak season. The median income in Greenbrier County, W.Va., population 35,729, is $39,746, below the West Virginia average of $41,751, according to U.S. Census data. West Virginia is one of four states with a median household income below $45,000.

For southern West Virginia to function, The Greenbrier needs to be filling rooms, dining seats and tee times. Residents struggle envisioning the quality of life in the region without the resort. “If it wasn’t for The Greenbrier – and I don’t know any numbers – but what would be here?” says Greg Caldwell, the assistant superintendent on The Old White TPC. The Greenbrier Classic has quickly developed into a major part of the region’s identity.

As Pope and other employees toured the grounds following the flood, a summer without the tournament was becoming a reality. PGA Tour official Ken Tackett visited the resort Saturday, June 25, 2016. He saw enough damage in his first 10 minutes touring The Old White TPC to comprehend the severity of the situation. The PGA Tour wasn’t coming to West Virginia in 2016.

“People could have left, people could have quit. Not a single crew member on our staff left. We have everybody here. They could have said, ‘No, I have been here for 15 years. I don’t want to do that anymore. I could retire.’ And nobody said, ‘I’m giving up.’ That puts it into perspective how much the job means to them and how much pride they have in everything. I think it’s very powerful.” —Josh Pope

Thanks to maintenance miracles, the PGA Tour has cancelled only two other tournaments, the 1996 Pebble Beach Pro-Am in California and 2009 Viking Classic in Mississippi, in the last 20 years. Even bringing the 2017 Greenbrier Classic to the site would require a miracle, according to many who saw The Old White TPC’s condition in the aftermath of the flood.

“It didn’t even look like a golf course anymore,” longtime mechanic Roy Young says. “People’s personal belongings, cars … you could barely see the tops of cars. It was filled with rock and gravel. Just seeing everybody’s personal property down there was something you couldn’t believe unless you saw it.”

The scope of the flood hit Pope when he reached the second fairway and noticed a jar of Vlasic Bread & Butter pickle chips. Pope, who honed his skills at elite private clubs, including Oakmont Country Club and Pikewood National, moved to southern West Virginia in 2014 to fulfill a career dream of becoming the host superintendent of a PGA Tour event. He never imagined spotting a pickle jar on a tour-caliber fairway. “That’s when you start to realize it was something bigger than golf and turf and grass,” he says. A photograph of the jar is still stored in Pope’s phone.

The flood destroyed much more than summer cookout plans. The disaster resulted in 23 deaths, including the sister of a crew member on the private Snead course at The Greenbrier Sporting Club. At least a half-dozen members of the resort’s golf course maintenance department lost either all or significant parts of their houses.

Full-sized coolers, bikes, red wagons

To help move lives and the community forward, Jim Justice, the billionaire who bought the resort in 2009, quickly decided to rebuild the golf courses, a massive challenged embraced by golf department leaders. “The only thing I knew we could do was knock it out of the park with what we were doing and do it as fast as we could so we could get these people back to work and guests coming back,” Shumate says.

Every member of the agronomic leadership team, including Greenbrier course superintendent Nate Bryant, whose house suffered major damage, visited the property the day after the flood. “You didn’t even really know where to begin,” Bryant says. “Even with your personal property it was like, ‘What do I do?’” Rebuilding the golf courses required assessing and documenting the damage for insurance purposes, a process that entailed Shumate’s managers working closely with vice president of golf Burt Baine’s professional staff.

Equipped with notepads and cameras, superintendents and assistant superintendents walked each course alongside golf professionals, documenting the extent of the damage on each hole. At the end of each day, they handed their materials to associate director of golf Jamie Hamilton, who created hole-by-hole checklists. “My knowledge of what was going on out there was on my computer screen,” Hamilton says. “It’s crazy all the things that were coming in. You were blown away by the things you saw.”

Hamilton even received a call from Caldwell about a smell originating from a debris pile on a meditation trail along the 16th hole of The Old White TPC. Was Caldwell sniffing human remains? Hamilton called resort security which contacted the police. “When as a golf professional do you ever think that’s the phone call that you are going to be getting?” Hamilton says. Animal remains caused the smell. Thousands of trout from White Sulphur Springs National Fish Hatchery, along with dogs, raccoons, deer and various other animals, flowed onto the property during the storm. The hatchery sustained $1.5 million in damages and 15,000 rainbow trout broodstock either died or were lost after water receded. Another 30,000 juvenile were exposed to the contaminated floodwater. “Big trout were just laying everywhere,” Young says.

Human bodies, unfortunately, also flowed onto the golf courses. The body of White Sulphur Springs resident Natashya Nicely Hughes, 33, was found on Greenbrier property nine days after the flood. “That was a bad day,” says Larry Allen, who has worked on the golf course maintenance crew since 2004. Hughes’ father Hershel Nicely, 68, and her son Dakota Stone, 16, were found dead on the property earlier. Search-and-rescue teams and cadaver dogs were regular sights for nearly two months. “We were scared that we would be working and you would find someone,” says irrigation technician Doug Moyer, a member of the crew since 2001.

“Just the dust was enough to drive you crazy. You go home and clean your ears every night, and it would be like black on Q-tips.” —Nate Bryant

Instead of preparing for a PGA Tour event, the crew returned to work and embarked on a golf reconstruction project with few emotional or physical peers. Land the crew had worked into what Pope described as “perfect” condition resembled something lurking behind thick, yellow crime tape, not thin, white golf gallery rope. “We had The Old White in fantastic shape for the Classic,” assistant superintendent Marty Maret says. “You busted your butt all spring and then that.”

Silty water mired by fuel leakage scorched vibrant turf. Powerful currents turned bunkers into muddy craters. Water crashed into a steel bridge and carried the structure 500 yards from its original spot. Potholes and cracks filled cart paths. Parts of the irrigation system were dismantled.

Managers understood the extent of the damage because of the superintendent-pro inspections. Shumate struggled finding the proper way to describe the damage – and the process that awaited – to a veteran crew. How do you tell people rebuilding their own lives their most fulfilling professional work was destroyed? “We stressed to them to take care of their own issues first,” Shumate says. “Once you can comeback, comeback and help us. But don’t rush things.”

Shumate warned the group they would see scarring images. He urged patience. But nothing fully prepared employees for their first looks at the courses. One rainy day ruined decades of labor.

“You don’t’ know where to start,” Randy Bittinger says. “It was a shock. It’s overwhelming. That’s what it was. With the golf courses, you don’t know where to begin.” The shock didn’t subside quickly. “It was unreal. I don’t know how to say it,” says Carrington Bryant, the superintendent of the Meadows course. “The amount of damage that quick … Fairways. Gone. Cart paths. Gone. Refrigerators, cars, boulders. It’s incredible the power of that water.”

Condiment jars, family pictures, gloves with the palms facing upward

The crew spent its first few weeks back at work removing debris from the golf courses while the resort’s leadership concocted an ambitious restoration plan. Some sections of The Old White TPC and Meadows course suffered more damage than others, but Shumate says a desire to provide guests with consistent playing conditions made reconstructing both courses the best option. Because it sits on higher land, the Greenbrier course suffered less damage, and the course reopened last July.

In a five-week stretch last summer, The Greenbrier selected an architect and contractor for The Old White TPC, ordered materials and established deadlines. Restoration guru Keith Foster was selected to oversee the efforts on The Old White TPC. A large crew consisting of Greenbrier employees and golf construction veterans from Maryland-based McDonald & Sons started the restoration July 27.

Design and construction decisions needed to be made in the field, although Shumate had been studying grass varieties for The Greenbrier Sporting Club’s new private course. Pope visited multiple Chicago-area courses last summer before construction started to further research grass varieties. The pair chose V8 bentgrass for The Old White TPC greens and T-1 bentgrass for the fairways. Any realistic shot of hosting the 2017 Greenbrier Classic required seeding greens by mid-September.

After years of mowing, raking, trimming, irrigating and spraying, members of The Greenbrier crew working on The Old White TPC and Meadows served as an extension of the construction team. They prepared The Old White TPC fairways for seeding by Fraze mowing the surfaces. Removing hundreds of acres of turf, combined with a dry and toasty July and August, created conditions resembling a “dust bowl,” says shop coordinator Curtis Persinger, a Greenbrier employee for nearly four decades.

Every full-time crew member returned to work following the flood despite a dizzying pace. Commute times doubled for some employees because of roads that remained closed for months. A few employees spent mornings and afternoons rebuilding the golf courses and evenings rebuilding homes. Knowledge possessed by longtime employees helped contractors with tasks such as locating irrigation lines, saving countless hours.

“People could have left, people could have quit,” Pope says. “Not a single crew member on our staff left. We have everybody here. They could have said, ‘No, I have been here for 15 years. I don’t want to do that anymore. I could retire.’ And nobody said, ‘I’m giving up.’ That puts it into perspective how much the job means to them and how much pride they have in everything. I think it’s very powerful.”

Managers and young employees made similar sacrifices. Anderson and Caldwell helped Pope handle the consuming demands of the sudden restoration a PGA Tour course. Anderson guided the crew through daily tasks and helped coordinator sand deliveries; Caldwell used water management tactics he learned in Texas to irrigate newly established turf. Nate Bryant, Carrington Bryant and Maret led work on the Meadows and Greenbrier courses. Greene, a Mississippi State student, extended his internship through the fall to help with construction.

Each deadline they hit brings normalcy a little closer. Or, as a lingering Greenbrier construction joke goes, every piece of sod they drop means less dust they must eat. “Just the dust was enough to drive you crazy,” Nate Bryant says. “You go home and clean your ears every night, and it would be like black on Q-tips”

The variable that altered their careers has cooperated throughout the past 11 months. Good weather permitted the team working on The Old White TPC to seed the final green on the evening of Friday, Sept. 16, 2016. Pope introduced his preferred seeding method to Shumate, Anderson and Caldwell, who seeded the first 17 greens. Shumate, Anderson and Caldwell pressed Pope to seed the 18th green, but Pope says he wanted one of his assistants to complete the job. Finally, after some chiding, Pope relented. Shumate recorded video, adding a symbolic and triumphant moment to an expansive multimedia library documenting the project.

Shumate convinced his bosses and senior PGA Tour senior vice president of agronomy Cal Roth, his team could also handle the logistics of seeding The Old White TPC fairways. The surfaces were seeded in both directions at a rate 1.80 pounds per 1,000 square feet by Aug. 26.

“It’s a constant thing. It never slows down. Every day is like you don’t have time to catch your breath. There is always something going on.” — Chris Anderson

A warm start and mild ending to the fall added optimism entering winter, which expedited the grow-in of greens and fairways. Crews continued laying fairway sod on the Meadows course into December, delaying the blowout of the irrigation system multiple times. “When your hand turns purple when you’re watering, it’s maybe time to blow it out,” Carrington Bryant says.

The winter was the “mildest in the last 10 years,” Shumate says. The entire team took Christmas off, but some form of work has occurred every other day since the flood. Contractors returned to The Greenbrier this spring and frantic activity resumed. Long weeks – think 90 to 100 hours – have been common since construction commenced. “It’s a constant thing,” Anderson says. “It never slows down. Every day is like you don’t have time to catch your breath. There is always something going on.”

A mid-April tour of The Old White TPC and Meadows revealed courses bracing for summer golf. Greens and fairways featured healthy turf with pleasant hues. Crews spent a comfortable morning placing sod around The Old White TPC tees and mowing stripped patterns into the Meadows fairways. “When I got here and looked at the golf courses that next day, I thought there’s no way we will ever get this back together,” Allen says. “And, look, we are almost there.”

Pride and humility prevent employees from disclosing the extent of their personal exhaustion. Reassembling a golf course is grueling, stressful and at times thankless. Natural disasters, though, push determined humans to unthinkable limits. Greenbrier Classic practice rounds begin July 3. A countdown clock in the maintenance facility break room reminds employees of how close they are to achieving a feat that will boost the morale of a recovering region.

“I think about it every day,” Pope says. “It’s a huge motivational force because it will ultimately show the resolve of the West Virginia people. I’m not a West Virginia native. I want to have it for those guys because I know how important this job is for them and how important it is for them to do say they did. It’s a monumental task to rebuild, but it shows you how strong the community is to get together and get this done from start to finish.”

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the June 2017 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Carolinas GCSA raises nearly $300,000 for research

- Advanced Turf Solutions’ Scott Lund expands role

- South Carolina’s Tidewater Golf Club completes renovation project

- SePRO to host webinar on plant growth regulators

- Turfco introduces riding applicator

- From the publisher’s pen: The golf guilt trip

- Bob Farren lands Carolinas GCSA highest honor

- Architect Brian Curley breaks ground on new First Tee venue