You’ve heard it from a player or member at some point: “I wish the greens were a little faster.” But chasing faster green speed isn’t the same as cultivating a high-performance green that serves the players best. A lightning-fast green could be a huge drain on inputs and resources, and still not provide players a solid playing surface.

There are more factors at play in keeping healthy, high-quality greens, says Paul Carter, CGCS, superintendent at The Bear Trace at Harrison Bay in Harrison, Tenn. A good green keeps its speed in balance with smoothness, trueness and consistency.

“It’s a combination of everything that makes a green work,” Carter says. “It’s a complex entity. We try to tell everybody, ‘Greens are living, breathing entities, and you have to treat them as such.’”

Even if a player is asking for fast greens, it’s important to keep those other qualities in mind, says Dr. Scott McElroy, professor of crop, soil and environmental sciences at Auburn University. “Speed is part of the putting quality, but it’s not the only factor,” he says. “I can take you to a smooth, concrete surface that’s extremely fast, and also unbelievably untrue. The ball is going to react wildly and erratically.”

A superintendent’s goal should be to balance the speed and firmness of the surface, and at the same time manage the turf to provide a roll buffer to keep the ball from veering at the first aberration or grain of sand, says McElroy. In fact, a high speed can highlight imperfections in the turf by decreasing the ball-surface contact, minimizing that buffer.

By slowing the green down a little and increasing the roll buffer, even a bumpy green can play a little more true. “If you slow the ball down, there’s more buffer there for any untrueness in the surface,” McElroy says. “You can only push the speed so far before you just lose control.”

Mowing practices contribute to maintaining the balance of speed and trueness, says Dr. John Sorochan, associate professor of turfgrass science and management at the University of Tennessee. His research focuses on how the quality of cut impacts the green surface. “We’re comparing a single cut versus a double cut, where you go mow perpendicular or backtrack, and what it does for green speed and clipping yield,” he says.

So far in his research, two years of data show that bentgrass greens improve trueness with a double cut program, with the second pass running perpendicular to the first, picking up slightly more clippings than either other method. The first year of data collected on Bermudagrass, however, shows that a single pass at a higher frequency of clip provides the best surface. “With a better quality of cut, you’re going to have healthier turf, which means it’s going to come back and grow faster,” he says.

For his ultradwarf greens, Carter avoids double-cutting as much as possible with his triplex mowers. When he needs to make up some speed, he sends rollers out, and can “pick up 6 to 8 inches on a greens roll” while cutting back on plant growth regulators, he says.

Rolling a green three days a week is always good for the turf, says Sorochan, smoothing the surface without damaging the plant. “[Rolling] is a better way to get your speed than it is to lower your mowing height,” he says. “Lowering the mowing height is something people get caught up on, and it causes too much stress. Superintendents have to avoid it.”

“I think 0.125 was the lowest we went this year on our greens,” Carter says. “We’ve gone below 0.100 before, but you’re putting the plant under so much stress at that height. It’s using all its carbohydrates, all of its energy just to stay alive.”

Raising cut height gives the turf a better chance to absorb sunlight and go through photosynthesis for an overall healthier plant that can absorb a footprint or ball shot more effectively. “When we raised the heights up, our greens got better, because now I’ve got more leaf blade up top for the ball to ride on,” Carter adds. “I’ve got more leaf blade to manage and manicure, where I can do some brushing and verticutting without getting down into the stolon and stems and really abusing the plant.”

He’s also strayed from a heavier schedule of verticutting, to avoid a cycle of verticutting the greens, then putting fertilizer on them to help them heal and recover, he says. “The more I tear my green up, the more I’m requiring of it to recover from that and be healthy, so I’m putting more fertilizer on it,” Carter says. “Then I’m going to grow more thatch. It’s just a circle of taking it out and putting it back. If you can balance your growth with your cultural practice, you don’t have to do either one as much.”

Topdressing is a big part of finding that balance for Adam Moeller, director, USGA Green Section Education. “Through the year, there’s ball marks, foot traffic and equipment wear and tear,” he says. “Topdressing plays a major role in just smoothing everything out. It’s extremely important in just managing organic matter.”

There’s no one-size-fits-all topdressing program, says Moeller, but a superintendent should topdress as often as necessary based on the plant growth. For most courses he visits, he says, that falls around once every one to three weeks.

The best putting greens go weekly with a light dusting of sand or once every two weeks depending on the budget or time, Sorochan says. “That’s always filling in those little imperfections and keeping that area smooth,” he adds.

Carter’s team topdresses right along those guidelines, with a light application once or twice a week if necessary to keep organic matter diluted so the grass doesn’t get spongy, he says. Though players’ first association when they see sand on the green is aerification, it lets the green putt more smoothly and receive a ball better.

Like topdressing, a nitrogen nutrition program should be spoon fed in smaller applications on greens. “You want light, infrequent nitrogen,” Sorochan says. “It’s like eating three balanced meals a day versus eating a huge breakfast and trying to get through the day. Maybe a little bit of nitrogen every seven days, so you don’t get those peaks and valleys in growth.”

Moisture management also benefits from frequent attention, says Moeller. In areas of the country without much rain, superintendents need to be on their guard and hit hot spots on the greens as quickly as possible, but all superintendents should use moisture meters with evapotranspiration (ET) information to dial in water requirements.

To find those hot spots, a superintendent can turn off the irrigation and let the greens dry down. Put on a pair of polarized sunglasses, and hot spots in the green will show up more clearly, Sorochan says.

Superintendents should base irrigation on the volumetric water content of the root zone, measured by a soil probe. If the turf starts to wilt at a measurement of 14 percent volumetric water content, the green should be watered when that measurement lowers to about 17 percent, until it reaches about 20 to 22 percent, or about where the roots are. “You want to keep it just above wilting to what we call ‘plant available water,’ which is 5 to 10 percent above whatever the wilting point is,” Sorochan says.

But it’s impossible to tell if a maintenance plan is working if there isn’t any way to measure results. Beyond Stimpmeter readings, Moeller recommends collecting data and creating a scorecard with targets for each green for smoothness, trueness and consistency, as well as speed.

“Where I’ve seen it done successfully, they took clippings from the same green every day. They built their dataset and started to understand where the greens were,” Moeller says. “They didn’t start making decisions from it instantly, but once they had a competent dataset, they really started to see how the little adjustments they could make had an impact.”

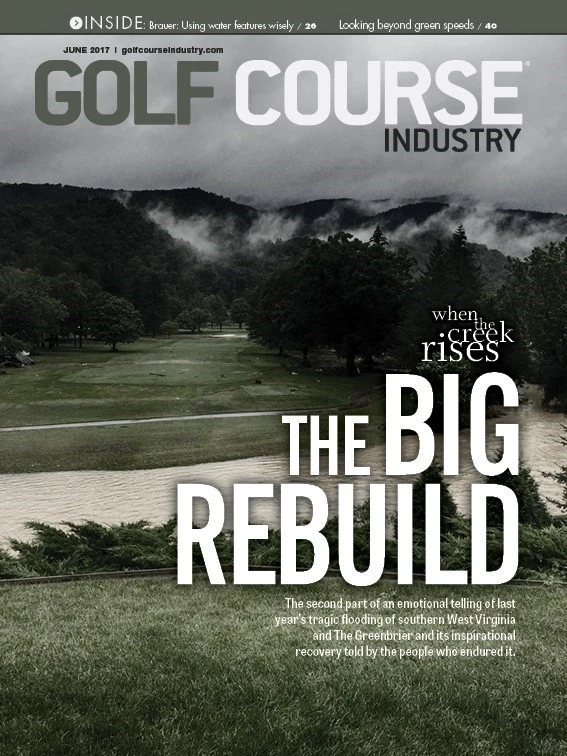

Explore the June 2017 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show