Ah, spring. It’s warm, the sun is shining and golfers are eager to get onto your course.

But before you produce that heady fragrant smell of freshly mown grass that sends golfers onto reverie, consider just how low you should go, with the first cut that is.

For both greens and fairways, the first cut of the season should be the same height as the last fall cut when the turf went into dormancy, says Dr. John Sorochan, distinguished professor and the turfgrass science director in the Center for Athletic Field Safety at the University of Tennessee. As the turf begins to grow, Sorochan says, superintendents will be mowing the dormant brown leaf tissue. For cool-season greens and fairways, mowing heights are not increased going into the fall. Rather they are occasionally raised during summer heat stress periods of June through August.

“For warm-season putting greens, the mowing height going into the fall occasionally is raised to keep dormant putting green speeds from becoming too fast,” Sorochan says. Still, during spring green up, superintendents will want their initial mowing to remain at the same height until the turf is actively growing. Lowering the mowing height going into late spring to early summer should be done incrementally over a few weeks and should coincide with grooming and light sand topdressing.

Michael Hileman, field and technical specialist at JRM Inc., ascribes to the “One-Third Rule” for most courses. “Incremental drops in height from there typically seem to be the chosen route,” he says. “Weather dictates all but have a plan ahead of time. I don’t think you can put a date on a first mow, but you can put a plan to the height when conditions call for mowing.”

An important step to take prior to the first mow is to roll the greens, says Dr. Karl Danneberger, a professor in the Department of Horticulture and Crop Science at The Ohio State University. Rolling — which includes the greens mower with reel disengaged — makes smooth the surface and reduces the likelihood of scalping with the first mow. “Scalping really stifles uniform early spring green up,” Danneberger says. “You will get varying ideas, but I don’t believe there is a standard percent increase. I would start at a higher height of cut and try to get down to normal height fairly quickly.”

For warm-season grasses, build the turf from the ground up after the last frost date has passed, and have mowing heights at levels that are cutting away most of that dead tissue, says Dr. Michael Goatley, turfgrass extension specialist and professor in the Crop and Soil Environmental Sciences Department at Virginia Tech University.

“Scalping is probably too harsh of a word to use but getting pretty close to a scalp cut is what I have in mind in order to remove as much of the dead material as you can,” Goatley says. “This stimulates a lot of new growth and development, but this is also why it is important to ensure that you aren’t going to have an extreme cold event that could damage succulent tissues. Then bring your turf up to its intended maintenance height for the rest of your growing season, tweaking it as needed for special events, etc.”

With cool-season turf, the first mowing events in late winter/early spring are usually happening at a time when environmental conditions and plant growth and development responses are tilted toward root development, often setting the stage for success in the coming growing season. “There is a lot of flexibility with lower mowing heights during this time of root development,” Goatley says. “And soon after there will be a flush of new stems from one of the year’s most active tillering periods.”

Turf density and playability can be optimized by closer, regular mowing at this time, but as temperatures warm and root development slows, plant health will be improved at taller heights of cut that still meet turf performance expectations.

For both warm- and cool-season grasses, Goatley says to keep in mind one of the most basic management, and that is “the difference between what you can do and what you should do when it comes to long term plant health. Don’t get greedy!”

The first cut of the season is solely dependent on the height of cut going into winter, says Luke Beardmore, senior vice president of agronomy and construction for OB Sports Golf Management. “As a rule, most golf courses and golf course superintendents will not cut more than 25 percent of the plant at one time,” he says. “In general, it is best practice to mow at most only 10 to 15 percent of the plant.”

“The height and timing depend on the grass type, which varies based on location, says John O’Leary, golf and sports turf sales manager for John Deere. While typically the height of cut doesn’t change from fall to spring, the species does impact the general height. He says in areas with warm-season grasses that go dormant, the height of cut is increased to help protect the plant during the winter months. This can be achieved by either raising the height of cut or by stopping mowing prior to the grass going dormant.

“The timing of the first cut is determined by the grass type and location,” O’Leary says. “Cool-season grasses, such as bluegrass, ryegrass and bentgrass, will green up much sooner than warm-season grasses, like zoysia or Bermuda. The mowing of cool-season grasses typically starts in early April, while warm-season grasses start in late April

The height of the first cut is important because scalping can delay green up. “As a best practice, aim to remove no more than one-third of the leaf blade at any mowing to avoid damage to the plant.” O’Leary says. “Mowing too high will not remove enough of the dormant leaf blade, making the grass appear less green. This may result in an undesired shaggy appearance.”

Cutting warm-season grasses too short in the spring followed by a cold snap could cause a lot of turf damage or setback spring green up, Sorochan says. Mowing too high will impact playability speed and consistency.”

Superintendents tend to incrementally adjust heights to where they want to be in the summer season. “The same can be said of the majority of cool season guys as well,” Hileman says. “But, everyone is getting to that ideal height of cut much faster into the season.”

Other factors that come into play, as well. For example, as superintendents want their turf to be growing and healthy heading into any spring cultural practices (aeration/verticutting, etc.) so as to ensure a fast recovery. “A superintendent I look up to in the Charlotte, N.C., area told me the goal is to return the greens back to the membership or customers as quickly as possible, Hileman says. “And mowing low too early could be very detrimental to their recovery.”

Hileman says weather dictates when the first cut should be made and how low the cut should be.

“Mainly, the first cut is typically dictated by temperatures, short term and long term, and the moisture level,” he says. “A ton of rain or soft conditions make it difficult to cut, so in those cases the mowers would typically be adjusted higher than the plan. “

Acknowledging that golf turf managers are “involved in a balancing act every day of the week” in their turf management programming, Goatley says meeting expectations of the public regarding playability while maintaining an actively growing, healthy turf is a never-ending process. “Pushing cutting heights to the very limits of possibilities is a stress-inducing practice that will ultimately reduce the health of the turfgrass, thus limiting its ability to handle environmental stress, and combat a variety of pests (weeds, diseases and insects).” All of these issues are likely to cause more damage and reduce the turfgrass’ ability to rapidly recover from the rigors of such intensive maintenance and use. “And never forget that it’s not just the grass that is stressed in these situations – it’s the superintendent too.”

The approach toward the first cut of the season has been affected by the trend toward faster green, and sometimes, fairway speeds, says Hileman. “It is obviously lower now than say 20 years ago,” he adds. “But, that is because you have to be at more demanding speeds all around. This in turn creates the need to have to get to the optimal height of cut earlier, beginning lower than sometimes needed.”

To be certain, turf conditions for professional tournaments and country club members are now centered around speed. But most golf courses were built in days of slower greens and more slope remains, Hileman says. “We have seen the market evolve with that change as well. Our very popular bedknives have progressively gotten thinner. With lower heights of cut, coupled with sloped greens, comes the need to have to watch things like dragging and scalping on greens mowers.”

Says Beardmore, “Most private club memberships tend to demand faster greens. This generally is accomplished through a variety of management strategies, and the height of cut is almost always one of them. The other key factor to consider is the severity of the contours of the greens. Lower heights of cut almost always leads to faster greens speeds, which can be negative if the contours are severe.” He adds that it is imperative for superintendents to find their “sweet spot” regarding green speed and height of cut.

“Everyone is a paying customer whether you are at a country club or a daily fee facility,” Hileman says. “They may not pay in the same manner, but they are all your customers. Superintendents have to be thick-skinned individuals. If a golfer leaves a putt short, the greens were slow. If they blow it by, the greens were too fast. The superintendent’s goal is to deliver the needs of the customer while balancing the overall health of the turf. You have to care about perception, but it is only a piece of the puzzle. You cannot sacrifice growing healthy turf for guys who have the need for speed too early.”

Superintendents risk the ire of golfers when it comes to the most valuable commodity a course has; the playing surface. If that means the greens run a little slow and the ball doesn’t bounce as high or run out as far on fairways in early spring, so be it.

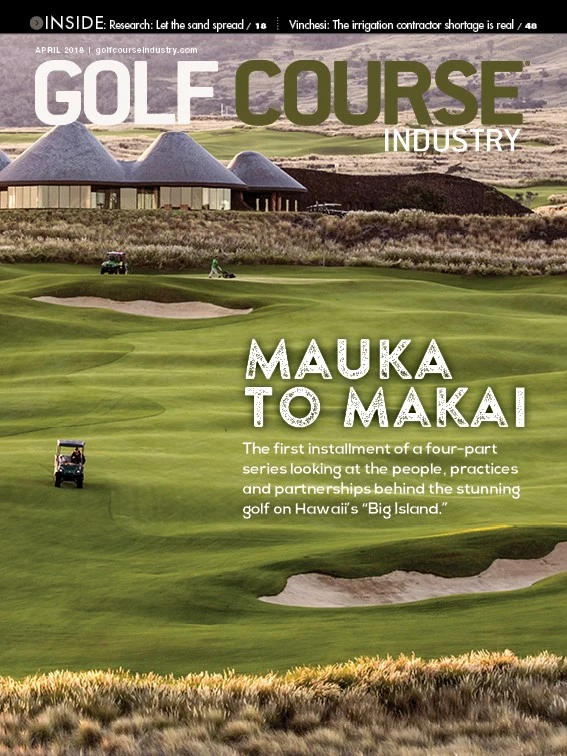

Explore the April 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show