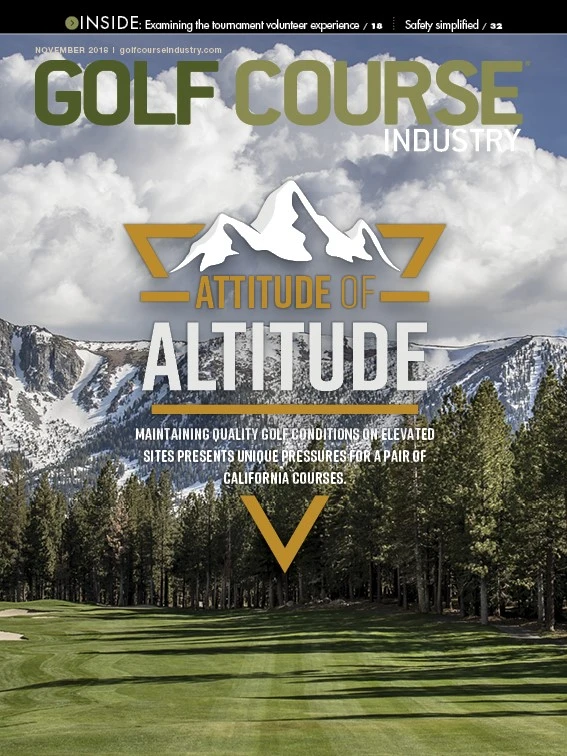

At two of the country’s most high-altitude golf courses, the pressures of operating at elevation aren’t just limited to the thin air.

Best known as popular California ski destinations, Sierra Star Golf Course (8,050 feet above sea level) in Mammoth Lakes, Calif., and nine-hole Bear Mountain Golf Course (7,000 feet) in Big Bear both trade the poles and snow for wedges and turf come the eventual late spring thaw.

Not that the transition isn’t without elevated pressures.

Respectively working with approximately 150-day golf seasons doesn’t yield a leisurely prep window, and while golfers are itching to get seasons underway, course managers and superintendents at both locales are battling the attitude of altitude.

Whatever tally a seasonal snowfall brings (or doesn’t) directly results into crucial choices for getting courses open fast, and in the best condition possible.

“The toughest thing for us is winter, and what the winter brings,” Sierra Star superintendent Patrick Lewis says. “We’re not just high elevation, we’re extreme amounts of snow. Last season was a light winter, and that was 260 inches of snow. The year before (2016), we set the record for inches of water, and that was over 600 inches of snow. So, come spring time, when your course is buried under 8 or 9 feet of snow, that presents some interesting challenges.”

Of course, winter moisture isn’t merely about inches when it comes to golf season – it’s also about the timing of those inches.

“This past winter (2017-18), even though we had a good snowfall, it really didn’t start until March,” Lewis says. “So, we ended up with some really dry areas; not our putting surfaces, thankfully, but what did happen was a lot of ice build-up, which really did a number on some places across the course. The challenge chasing that, being at such high elevation, is that we’ll get snow until June. We’re trying to open for Memorial Day, and it’s freezing at night, which doesn’t result in a lot of germination when you’re trying to re-grow at that time of year. It can be a struggle to get things in really good shape early on.”

Taking advantage of a compact golf season requires heightened creativity and flexibility.

“We have a pretty short window to make hay when the sun is shining,” says Dave Schacht, director of golf and head golf professional at Sierra Star. “I don’t even refer to ‘rounds’ anymore. I call them ‘starts.’ We average about 100 starts over 150 days and do around 15,000 rounds. It could be a three-hole loop of play and lunch, or a super twilight round at 4 p.m., a five-hole round at 5, or a nine-hole round as we work to court the millennials.”

At historic Bear Mountain, the enhanced ball flight of elevated play has been testing club selection since 1948.“Probably the most challenging aspect is that we’ve got about 90 days of growth; good growth, where we’ve got the soil temps where they need to be, and it’s not too cold,” Bear Mountain director of golf Bjorn Bruce said. “Beyond that, it’s about a lot of preparation prior to the grow season, and then a lot of preparation putting the course to bed at the tail end of it and getting ready for winter.”

For course operators, fluid futures can bring tough lessons. After a previous year’s snowfall of 90 inches, Big Bear saw a mere 26 total inches in the winter of 2017-18, 4 of which flaked down in April. The average snowfall in Big Bear is about 62 inches. With the root base basically dead on certain portions of the course and soil temps only in the high 40s into May, last winter proved a dramatic inverse from seasons’ past.

“We’ve had our challenges this year,” says Bear Mountain superintendent Dave Flaxbeard, who also has worked at courses in Los Angeles and the Coachella Valley. “Last year and the year before, I got back here April 1, and mowed the greens the same morning. By the time we hit mid-January this season, most of the damage was already done. And when I got back, the weather didn’t allow me to do much culturally. I tried verticutting, but nothing.”

With a lack of snowfall and/or spring rain, options to irrigate can be limited. “Our irrigation system is off during winter. It’s frozen,” Bruce adds. “You can’t turn it on or it will explode. So, we need to drain the irrigation, pump out the lines with an air compressor. And then, this past winter – it doesn’t snow. So, it’s like, ‘How do you get water out there? How do you water your greens?’ We have a 500-gallon tank we have access to, yet it’s 20 degrees outside. But the greens are dry and need water, but then if we water, it’s going to turn to ice. It’s all pretty wild.”

While both Sierra Star and Bear Mountain use a combo of ryegrass and bluegrass fairways and Poa annua and bentrgrass mixture on the greens for sustainability and heartiness, the high altitude locales need ample prep for the expectation of snowfall – whether it arrives or not.

“We run into trouble when we get a really cold fall, and then don’t get snow until January. That’s when we really start to fight with the sustainability of the turf,” Schacht says. “We’ve had some tough openers, but Pat has really learned from past experiences. We throw a ton of sand down on the greens, but Mother Nature is really in charge. We just rent the place.”

Schacht keeps close contact with other elevated locations in California on successful maintenance practices, though the option of covering greens hasn’t been employed at his track.

“We just use sand. We’ve found that’s the best,” Schacht says. “California is sorta’ hard in what the state will let you put down for chemicals, so that can be tricky. So, we just go with sand. We haven’t used any covers.”

At Bear Mountain, covering greens with burlap sacks has been sampled with a modicum of success. “Sometimes I do cover in (early spring), though that’s very labor intensive with the turf spikes, and it takes forever,” Flaxbeard says.

Lewis has considered borrowing a straw cover technique often seen at courses in the frigid Upper Midwest. “But I don’t know if we could do that here, because it’s so darned windy,” he adds. “Of course, then we’d need to figure out how to get straw, because one of our other biggest challenges being at this elevation is that we’re also in the middle of nowhere.”

In Big Bear, Flaxbeard treats greens with snow mold prevention and uses a wetting agent to keep moisture on top of the turf. The highest elevated course in California, Sierra Star also must brace annually for snow mold issues. “We do our snow mold applications, and I try to time that accordingly, along with finding the right product and rotating the products,” Lewis says.

Between ample snowfall and a dry winter, both locales would surely seem to opt for the former option. Even when a massive snow dump results in plowing greens. “We use a 6½-foot PTO-driven snow blower on a tractor, and even go so far as to use a skid loader on the putting surfaces,” Lewis says. “You have to be very careful. If you miss, of course, you can really get rid of some turf.”

More winter flake fall results in welcome work for course staff. “Coming out of last winter, it was great – a lot of snow, a lot of moisture, especially in the spring,” Bruce says. “We couldn’t mow enough. It was too much grass and lush everywhere, and that’s a great problem to have.”

Despite remote locations, neither Sierra Star nor Bear Mountain feel affected by labor issues, as both enjoy split-staffing power shared between slope and course employees basically going from one job to another with the seasons. “We don’t have the biggest crew, but we have the right crew,” Bruce says.

Come a winter’s freeze and eventual thaw, Bear Mountain’s tight staff is tasked with “bringing in everything,” according to Bruce, with yardage markers, hole monuments, protective netting, benches and ball washers all hauled indoors before an inverse occurs in the spring.

“Courses down the hill, they don’t have to deal with any of that,” Bruce says. “Up here, it’s pretty much shutting down a business and then starting it again from scratch twice a year, every year.”

Such seasonality also directly impacts course brass. To wit: Schacht and Bruce work ski operations in their respective destinations come winter, and Flaxbeard works the Bear seven months out of the year. “I have a calendar and better check it,” Bruce says. “When you’re in the middle of the winter operation, the last thing you’re thinking about is, ‘I wonder what the greens are looking like right now?’ You just can’t get caught with the pants down.”

Explore the November 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show