Great golf courses are designed to foster good golf. Golf course architects are stereotypically viewed as masochists. In reality, we try to provide a collection of doable shots for all levels of golfers … well, most of the time. Whether felt “in the gut” way back when, or known because of recent scientific study, we understand the relationship between golfers and the course.

Golf course architects are fond of saying “there are no rules,” but some general golf course architectural principles have developed over decades. These are often based on golf certain physics truisms, the notion of “proportionality” and knowledge that golfers prefer to shoot a decent score, meaning we recognize:

- The relationship of shot difficulty to shot length (longer is harder)

- That punishment should fit the crime

- That shot difficulty should relate to success on the previous shot.

Allow me to explain.

The relationship of shot difficulty to shot length

In general, longer shots are harder than shorter shots, because:

- A 200-yard shot 5 degrees off line flies twice as far off line than a shot 5 degrees off line from 100 yards.

- Lower lofted clubs are harder to hit than higher lofted clubs.

Several design axioms spring from this, including theories that:

- Longer approach shots need bigger greens (and wider fairway approaches) than shorter approach shots.

- Longer shots also receive deeper greens, because average golfers get less back spin on lower trajectory shots.

Similarly, greens (and fairways) should be wider on uphill shots, or shots into the wind, as head winds deflect shots off line to a greater degree. Further, many believe greens on long iron approach shots should, compared to shorter approach shots, be/have:

- Flatter front to back to allow shots to roll to back pin positions

- More gently contoured

- Lower to the ground, to allow for lower loft, roll-up shots.

Punishment should correlate to the degree of miss

We hear this from tour pros and low handicappers, who expect systematic reward and punishment, leading to things like:

- Intermediate rough cut.

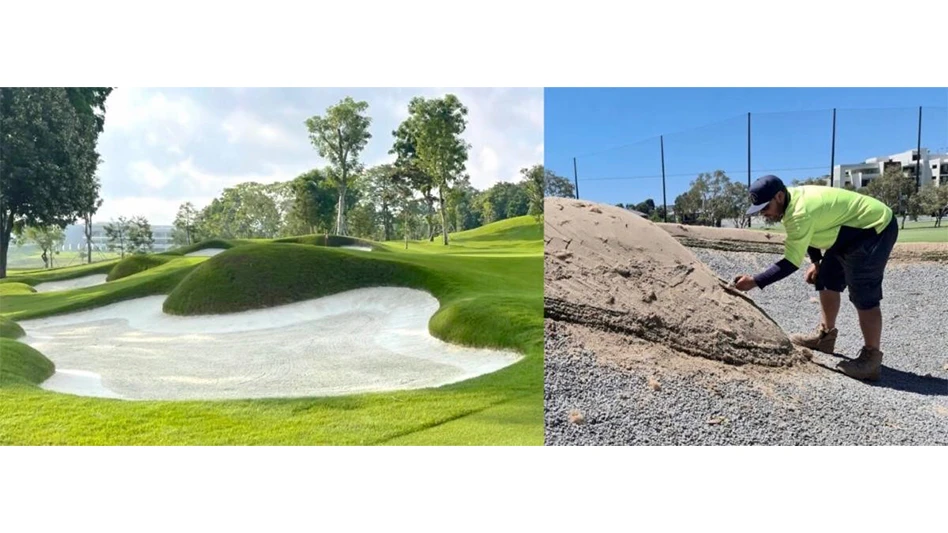

- Flat green side sand bunkers with steep (and tightly mown) banks. Eliminating sloped sand near the green reduces plugged lies for shots missing the green by 10 feet, while a 20- foot miss finds flat sand and a good lie.

This isn’t a new thought. Donald Ross built fairway sand bunkers that were deeper on the outside edge to punish wider misses more harshly than shots that narrowly missed the fairway and found the inside edge of the bunker. However, Ross was also careful to sharply slope the last few feet of sand all around the bunker, believing it was unfair for any shot to have randomly have an unplayable lie up against the bunker lip. Historically, architects build deeper green side bunkers than fairway bunkers, reasoning golfers will use high lofted sand wedges.

Shot difficulty should relate to success on the previous shot

This is a tenant of classic strategy in that a golfer who plays a higher risk shot off the tee is usually given the advantage of an easier second shot. It is often applied more generally in design for balance.

For example, one architect would rank the tee shot, approach and first putt as easy (1), medium (2) or hard (3). He believed that most par 4 holes should have rankings around 5-7, for mid-difficulty, but with a mix of where the difficulty lies. Holes would be too hard if the shots ranked 3-3-3=9 or too easy if ranked 1-1-1=3. He would only design a select few holes at 4 or 8, either when the land demanded it or specifically to create harder or easier holes for variety.

Some architects believe difficulty should generally increase as the round progresses, starting with an easy opening hole, and finishing with more difficult holes to help determine the better player in a match. Others strive for some rhythm and balance of holes, avoiding any stretch of extremely hard or easy holes for variety.

None of these general rules trumps the architect’s cardinal rule of relating the golf hole to the land itself. It is rarely satisfactory to put “five pounds of green on a four-pound green site.” Having a somewhat random mix of greens, and perhaps a touch of whimsy, is just as important as any hard and fast rule or theoretical design axiom.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the January 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Toro continues support of National Mayor’s Challenge for Water Conservation

- A different kind of long distance

- Golf Construction Conversations: Stephen Hope

- EnP welcomes new sales manager

- DLF opening centers in Oregon, Ontario

- Buffalo Turbine unveils battery-powered debris blower

- Beyond the Page 66: Keep looking up

- SePRO hires new technical specialist