|

The use of plant growth regulators (PGRs) in suppressing seedheads has grown in popularity. The theory is seedhead suppression creates heartier plants due to the misdirection of energy away from seed production and into plant reserves. “If a superintendent can go from 50 percent Poa to 10 percent over two years in fairways, once they get to the 10 percent level they may not even need to apply Embark or Proxy. So a more long-term fix to reduce the Poa population eliminates having to use some of the Poa seedhead inhibitors.” John Gallagher, superintendent of Race Brook Country Club in Orange, Conn., has begun experimenting with applications of PAR mixed in the tank with Embark or applied a few days after the application of Embark to mask the yellowing. He also uses more potassium sulfate to keep the turf green in colder weather without surges of growth. “The biggest challenge I face regarding the suppression of seedheads is explaining to the golfing membership why the turf goes off color once the Embark takes effect,” Gallagher says. “I write articles to the membership and post photos and relevant magazine articles. I think I’ve been using Embark for so long that the membership doesn’t remember what it’s like to play or putt on turf that’s gone to seed.” Another method to reduce the temporary yellowing is tank mixing Embark with Ferromec AC Liquid Iron, which contains nitrogen, iron and sulfur. When Ferromec is added, seedhead suppression has reportedly decreased by 10 to 15 percent. For the past 15 years, Gallagher has pretty much followed the same routine to suppress seedheads. He applies Embark roughly the first week of April to greens, tees and fairways but in that application is also a fungicide for leaf spot prevention and liquid iron to keep the turf green. After about a week, he topdresses greens and lightly grooms over the next few weeks to help remove any seedheads that appear. He may verticut depending on the weather but he usually doesn’t that early in the season. He also may apply Embark again if the weather gets unusually warm about three weeks after the initial application in order to stay seedhead-free. About 10 to 14 days after that, he begins his Primo and Cutlass season-long applications to greens, tees and fairways. The issue to be wary about with verticutting is potential damage to the turf. Verticutting can eliminate some of the seedheads on a putting green after emergence, but this tactic doesn’t prevent the formation of seedheads. The equipment must be properly adjusted to avoid damage to the turfgrass plants, and the mechanical removal of seedheads will need to continue until seedhead production ceases. In Gallagher’s region, timing PGR application is very tricky because in the Northeast, the weather doesn’t cooperate a whole lot in April. He has found, however, that the timing isn’t as critical with Embark. Jim Ryerson, superintendent of Two Oaks North Golf Club in Wautoma, Wis., agrees that timing can be a challenge. “In Wisconsin, no spring is ever normal,” Ryerson says. “Last spring was very cold, very wet and very snowy. We verticut a couple of times, but couldn’t topdress very often with the wet weather.” Ryerson was sort of a stranger to seedhead suppression as he had never had to do much about it because it had never been much of an issue. But that all changed during the last two to three years. He first used Primo Maxx, verticutting and topdressing. Last spring, however, he used Embark and, after calculating the GGD (growing degree days), applied 30 ounces per acre on May 12. He then made an additional application three weeks later on June 6 and says it worked pretty well. |

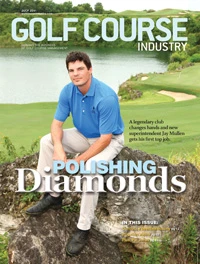

Explore the July 2011 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Advanced Turf Solutions’ Scott Lund expands role

- South Carolina’s Tidewater Golf Club completes renovation project

- SePRO to host webinar on plant growth regulators

- Turfco introduces riding applicator

- From the publisher’s pen: The golf guilt trip

- Bob Farren lands Carolinas GCSA highest honor

- Architect Brian Curley breaks ground on new First Tee venue

- Turfco unveils new fairway topdresser and material handler