| Next time you are on an airplane, look out the window at the golf courses you’re passing over. Can you see the burn? It’s from this vantage point where the fine art of striping really stands out. And, while you don’t need to see the stripes from 1,000 feet to appreciate yet another one of the modern superintendent’s talents, when striping is done well, it’s aesthetically pleasing from any vantage point. For cool season grass courses that only open for six months of the year, it’s essential that superintendents burn in the stripes right from the first cut of the season. This sets the guidelines, so staff know where to cut for the rest of the year. It’s part art and part science. You need to cut it at the right height, so the grain of the grass doesn’t lay down too far to one side. Brent Thompson, superintendent at Mountaintop Golf and Lake Club in Cashiers, N.C., starts mowing in his stripes beginning in late March. The course, which has bentgrass fairways, usually opens May 1 and shuts down the Sunday after Thanksgiving. “We will start mowing in late March and for the first six to eight mowings up until mid-April, I will mow dark and light or round and round, which is pretty much the opposite direction of what I do when I burn in my stripes,” he explains. “I’ll mow the first five or six times in a different direction; then, I will burn in the stripes in late April and do that all the way until late October.” Thompson does this because he believes the cross-cut helps stand the grass up a bit more. “Your stripes are a lot more vivid and the guys know which way to mow every time,” he says. “They just really stand out when you burn them in.” Thompson, who has been at the club since 2006 when this Tom Fazio design nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains opened, stripes in a diamond cut in two directions. “I mow them right to left and then left to right to get the diamond cut,” he explains. “I mow in the same direction on each line and mow down the light stripes. When going from tee to green, I start in the middle and then work my way out.” Groomers on the mowers and grooved rollers help Thompson and his crew keep the grass down. He says the only negative against this practice is if you don’t cut the grass short enough, you get longer and leafier blades, creating a grain that is not acceptable to players as it results in inconsistent lies on the fairway. His crew mow the fairways at roughly 400,000ths of an inch. “The height of the cut definitely makes a difference,” he says. Towards late October, Thompson and his crew return to cutting the fairways round and round. Mountaintop members are happy with the conditions and the striping makes the course more aesthetically-pleasing. From the Blue Ridge Mountains to the California Coast, Pebble Beach beckons for a striping story of its own. The course that tops the bucket list wish for most golfers and host of the PGA Tour’s AT&T National Pro-Am is a place Jack Holt is lucky to call his home away from home for the past 30 years. Holt is the assistant superintendent at Pebble Beach Golf Links. He gives me a bit of a history lesson on striping before talking about what they do at the greatest public course in the United States. “Different grasses react in different ways,” he says. “Originally, striping was a method of making sure you got a different direction each time you mowed to improve the quality of the cut. As you mow, the grass gets pressed down in the direction you are mowing on the cutting unit and if you cut the same way every time, pretty soon you get an elongated growth pattern or you are not getting an effective cut – you are just pressing the grass down. So, you change direction each day to make sure that doesn’t happen. “But it evolved to a thing where aesthetics was as important as quality of cut in some people’s opinion,” he continues. “That’s where fancy striping happened. People got more concerned with the look than the real purpose of mowing.” Holt says striping is all about striking a balance between agronomics and aesthetics. “It can actually take away from the aesthetics of the golf course. You think it looks good, but it’s not to the benefit of the course. You want something that makes agronomic sense and enhances your aesthetics rather than put all the attention on the stripes you’ve just put down.” At Pebble Beach they vary their striping throughout the year. The advent of new equipment and smaller cutting units has given greenkeepers more options and leeway to the types of stripes they can create. “Sometimes we will do a shadow cut, which is up and back,” he says. “For the U.S. Open last year, we cut everything in the same direction because the USGA didn’t want any stripes. For our other televised tournaments we do a diamond cut. We think that enhances our aesthetics and shows off the contours of the fairways.” There is a lot more to striping than meets the eye, Holt adds. “Many think it’s haphazard, but there really is a lot of thought and consideration that goes into it.” While some courses stripe year-round, others tend to use this practice solely before hosting major tournaments. Pat Moir, superintendent at Hillsdale Golf and Country Club, Mirabel, Quebec, Canada, says he will start striping leading up the LPGA CN Canadian Women’s Open, which is happening at the club this August. “In my mind, it’s all aesthetics,” he says. “Everybody has a different view as to what they think looks good or not. As an example, I tried it last year and used the same mowing pattern on the fairways. Some members said the striping looked really good, then others said ‘why don’t we have the checkerboard pattern we used to have or that club down the road has,’ so it really is a matter of taste. “What I’ll do leading up to the event is inform my board and membership through our newsletter that the main body of fairways will be striped in the half-half mowing pattern,” he continues. We will mow up one side, then turn around and come back on other side to burn it in. It’s basically a throw-back look to when they didn’t have riding fairway mowers. They had pull-gang fairway mowers and guys couldn’t turn in the rough or they would mow the rough, so guys would start mowing and they would stay on the fairways and mow like a Zamboni. They’d go up one side then turn around and go down other and then work your way out from there, but always going up the same half and always going back down the other half – this results in a light stripe on one side on half the fairways and a dark stripe on the other half of the fairway.” When it comes to equipment, you can use most mowers to burn in lines on the fairways. Tracy Lanier, product manager at John Deere Golf, who has been with the company for 21 years, says any reel or deck mower can give you the ability to stripe. “We do things a bit different with our fairway mowers that can help in the striping of the turf,” he says. “We have hydraulic down pressure on our cutting units, which is basically taking weight on the traction unit and putting it down on the cutting unit. It’s going to stripe better because it is staying in contact with the turf and pressing down on it more. “We also have a brush option that can go between the front roller and the reel … it’s a gear-driven brush,” he adds. “This can help to burn in stripes. You brush the turf … just tickle grass to help it stand up more and give it darker/more pronounced stripe.” Why not leave the last word on the subject to Tim Moraghan, principal at Aspire Golf, who knows a thing or two about striping. A former superintendent, Moraghan spent 20 years working for the USGA preparing golf courses for national championships. “The first line is the most important,” he says. “Guys have to choose their direction … almost streamline it sometimes. A lot of guys told me they like to work from putting greens and work back to the tee as it seems easier to lay the line down. It’s an exact science for these guys and it takes a lot of work. “For courses holding a major tournament like the U.S. Open, they know there are going to be a lot of aerial shots from the blimp, so you want your lines as straight, tight and uniform as possible because they are going to take a picture from 1,000 feet in the air and you don’t want it to be sloppy.” |

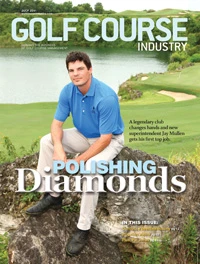

Explore the July 2011 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show