Duininck Golf overcame a litany of logistical challenges to resurrect a historic golf course destroyed by Hurricane Katrina.

Duininck Golf overcame a litany of logistical challenges to resurrect a historic golf course destroyed by Hurricane Katrina.

Mother Nature can be very unforgiving. Forget about winter coming early or a wet spring that delays the start of a season. When Hurricane Katrina roared through the Gulf of Mexico and devastated much of New Orleans, the weather became a matter of life and death, not just rounds lost.

When the Big Easy's levee system failed the morning of Aug. 29, 2005, Joseph M. Bartholomew Sr. Golf Course was one of the casualties. With more than 1,800 people losing their lives in the hurricane and subsequent flooding, golf was just an afterthought. But once the city and citizens began picking up the pieces of their lives and returning to normalcy, recreation came back into view.

Bartholomew Golf Course had a storied past before Katrina, dating back to the 1950s. At a time of segregation in the United States, the course – originally nine holes and a part of Pontchartrain Park – was developed by the city and opened for use by African Americans in 1956. In 1979, the course was named after Joe Bartholomew, who designed and built the course, and was its first golf professional.

While Duininck Golf is being recognized with Golf Course Industry's Heritage Award for its work starting in July 2009, in restoring this part of New Orleans history, the builder was originally onsite in 2005.

Duininck was first contracted to cap three fairways with plating sand, rebuild tees, repair irrigation and grass the work. This was completed and turned over to the city that summer. New Orleans was set to reopen the course, along with a renovated clubhouse and various improvements, when Hurricane Katrina struck.

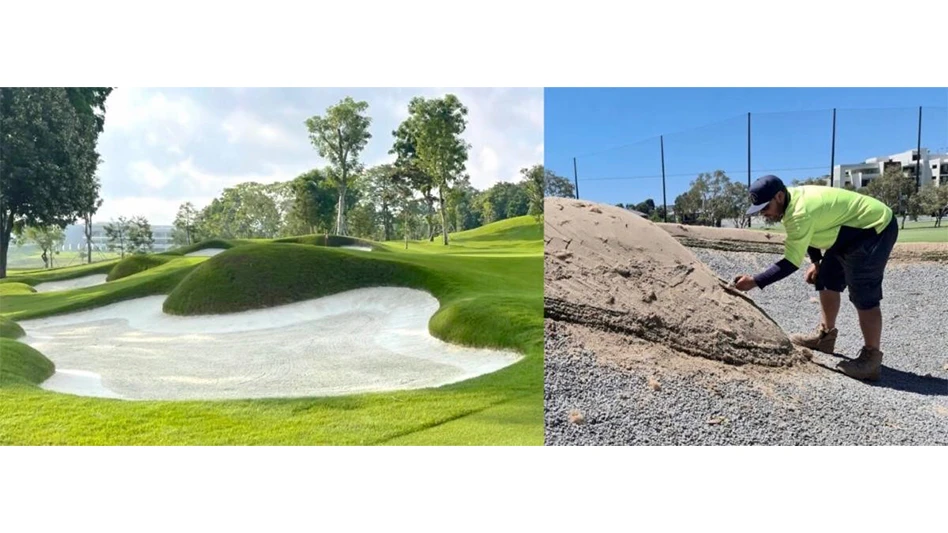

The Joseph M. Bartholomew Sr. Municipal Golf Course was devastated by Hurricane Katrina, but Duininck Golf rebuilt the course, helping the local community and economy to heal. The Joseph M. Bartholomew Sr. Municipal Golf Course was devastated by Hurricane Katrina, but Duininck Golf rebuilt the course, helping the local community and economy to heal. |

The course sat underwater for weeks while the city was being pumped out and an initial cleanup was done by FEMA. Bartholomew laid vacant for nearly four years. On July 7, 2009, with architect Garrett Gill's designs in hand, Duininck Golf broke ground on the reconstruction of Joseph M. Bartholomew Sr. Municipal Golf Course.

The Pontchartrain neighborhood still bears the signs of destruction. Gill and Duininck's objective was to reconstruct the entire golf course to a similar routing plan and have it completed for a spring 2011 opening, which would help revitalize the economy.

"Joseph Bartholomew was a combination of renovation and rebuild," says Judd Duininck. "Garrett Gill did an incredible job of salvaging as much of the original design as he could. The basic routing was reused and features in the same locations. With the numerous aged live oaks and cypress that lined the course, there wasn't much room for change."

Gill, who worked closely with Kelly Gibson, a lifetime member of the PGA Tour and native of New Orleans, focused on and reused some of the unique features that were on site such as "Bird Island," according to Duininck. New green complexes and bunker features were developed, and a few tee locations changed to accommodate today's technology.

"The intent was to preserve the strategy and characteristics of the Bartholomew routing," Gill says. "We were fortunate that characteristics of the course were preserved."

Following Katrina, Gibson began a passionate pursuit to involve himself in the "rebirth" of his hometown.

"It's important for me that I give back to the community that served me throughout my career," he says. "New Orleans has an opportunity to become a golf destination post-Katrina."

Gibson also was instrumental in the design of an elaborate First Tee facility at Bartholomew.

As the news repeated in the days and weeks following Katrina, New Orleans sits below sea level. Drainage and irrigation mainline excavations were into the water table and had to be dewatered continually. Lake level connector pipes needed to be raised, which saved the owner on the lengths of pipe needed. An additional laborer was adds to the crew to aid in the production, which enabled the crew to install and get backfilled quicker.

Because soil conditions were unacceptable for building a golf course, the dirt was laid out in lifts. Long-reach excavators were needed to dredge existing ponds and Marukas – a track-type dump truck – was used to haul dirt to features. A good, sandy soil was found in a few areas on the course, which were graded first, allowing the drainage, greens construction and irrigation crews to continue work and get these holes nearly completed while the dirt was drying on the other areas.

"Soils in New Orleans are definitely the toughest soils we have encountered," Duninck says. "Harris Duininck, one of the senior partners in our company was on a project we had in New Orleans with me one day and says: 'Judd, if we come out of this project making any money you can say that you have accomplished something, as I haven't seen conditions this tough as long as I have been around the business, and that is over 50 years.'

"Having built courses in New Orleans in the past there is one thing you need, and that is patience," Judd Duininck adds. "The dirt moves slow and dries slow. In other parts of the world a golf course contractor can use large excavators, scrapers and haul trucks. In New Orleans you get to use Marukas with a half load on them. Like they say, 'patience is a virtue.'"

Finding qualified contractors to meet the Disadvantage Business Enterprise requirements was difficult for Duininck. An earthmoving subcontractor had to be replaced and their work was completed by Duininck to keep on schedule. The additional costs were not anticipated, but had to be assumed.

Finding qualified contractors to meet the Disadvantage Business Enterprise requirements was difficult for Duininck. An earthmoving subcontractor had to be replaced and their work was completed by Duininck to keep on schedule. The additional costs were not anticipated, but had to be assumed.

The first cap sand contractor had to be replaced, as well. Spot checks on truckloads of sand were coming up short of what was billed. Considering more than 50,000 cubic yards of sand was used, losing more than a cubic yard of sand with each truck would have led to a shortage of more than $75,000 worth of material. Duininck tapped a prior relationship with a contractor and negotiated a deal that provided the correct amount of material for to the project at a price that met the expected budget.

The original start date of April 1, 2009, was moved back a month, then to July 7. Much of the prime earthmoving months were lost and a spring 2011 opening faced the team. Despite subcontracting issues and an average annual rainfall of 86 inches, the course needed to be shaped in time for the ideal sprigging period of March and April. Duininck adds personnel during the winter months while colder-climate projects were shut down.

"Despite the late award, our construction superintendent, Ahren Habicht, and his team did an outstanding job of fast-tracking the schedule. We were still able to successfully plant the course over the summer and grow it in for a fall turnover to the City of New Orleans," Duininck says. "With the city having a construction management firm to manage all of the reconstruction projects in New Orleans, and funds coming from three different sources – FEMA, City Block Grant Funds and Capital Projects – getting any requested changes through the system took longer than anticipated."

Throughout the process, Duininck Golf was to report to one individual – the construction manager for the City of New Orleans. From the pre-bid to final acceptance, five different project managers were assigned to the project. Gill and Habicht were diligent in keeping accurate communications and Habicht would spend hours getting each new construction manager up to speed, which kept the project moving forward.

Though the project started July 7, the first month's work was not paid in full until around Thanksgiving. A local construction attorney was used to consult with for advice on how to get payment out of the city, which resulted in action being taken by MWH Management and the City of New Orleans. Money was ultimately paid. Because of the poor soil conditions, haul roads were constructed out of plating sand to allow trucks to maneuver through the site. In addition to sand for each hole, which was calculated in advance, these haul roads were used to bring in concrete for cart paths and greensmix for tees and greens. In areas that were too difficult to maneuver trucks, dump carts were utilized to add the needed materials.

"Getting materials into the features and concrete to the cart paths is always a challenge in New Orleans. Joe Bartholomew was no exception," Duininck says. "Dump carts and Marukas got quite a bit of use.

"As far as easier, it was great to have PGA pro Kelly Gibson on the Gill design team," he adds. "With Kelly living in New Orleans, we were able to get design decisions made quickly."

A prolonged dispute between the city and power company forced Duininck to go without power for more than five months at the beginning of the project. While Duininck was able to complete work not requiring power (much of the irrigation system was completed and only needed to be flushed and programmed when power was established), grassing the course was in serious jeopardy. Once power was provided and a pump station installed and operational, grassing was fast tracked from a schedule of 104 days to just 61.

"In the history of golf courses, this little construction window is just a small blip," Gill says. "We're extremely proud of the project and proud of the City of New Orleans for caring about it. It was a remarkable effort and I think golfers will find it a remarkable course to play."

Duininck concurs.

"We as a company are so proud of how the Joseph Bartholomew course finished out," Duininck says. "Garrett Gill, Jon Schmenk, and Kelly Gibson did a fabulous job of tailoring this course to fit the property and the needs of the community. The course is going to be a real anchor, and hopefully rejuvenate the historic Gentilly community of New Orleans."

Explore the September 2011 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Toro continues support of National Mayor’s Challenge for Water Conservation

- A different kind of long distance

- Golf Construction Conversations: Stephen Hope

- EnP welcomes new sales manager

- DLF opening centers in Oregon, Ontario

- Buffalo Turbine unveils battery-powered debris blower

- Beyond the Page 66: Keep looking up

- SePRO hires new technical specialist