This has never been attempted. U.S. Open in the Pacific Northwest. Abandoned gravel and sand mine. Municipal course operated by a management company. In an industry where science aids turfgrass managers, what will happen at Chambers Bay, a vast property along the Puget Sound in University Place, Wash., next month ranks among the biggest agronomic experiments in American golf history.

This has never been attempted. U.S. Open in the Pacific Northwest. Abandoned gravel and sand mine. Municipal course operated by a management company. In an industry where science aids turfgrass managers, what will happen at Chambers Bay, a vast property along the Puget Sound in University Place, Wash., next month ranks among the biggest agronomic experiments in American golf history.

The United States Golf Association is bringing its signature event to an 8-year-old course with fine fescue tees, fairways and, yes, even greens. There’s no guide to finessing fescue for a U.S. Open while supporting 35,000 rounds per year, and the volume of American-focused research on fine fescue greens is limited compared to other turfgrass varieties.

If such a thing as an American fine fescue culture exists, its origins can be traced to the system that prepared Chambers Bay director of agronomy Eric Johnson and superintendent Josh Lewis for their current positions. Johnson and Lewis work for KemperSports, the Illinois-based company that manages Chambers Bay, which is owned by Pierce County, Wash. KemperSports also manages Bandon Dunes, a renowned resort along the Oregon Coast 380 miles south of Chambers Bay.

Few considered the possibility of wall-to-wall fescue on an American golf course until businessman Mike Keiser combined with European agronomist Jimmy Kidd and his golf course architect son David McLay Kidd to bring bold, throwback philosophies to Bandon. Johnson arrived at Bandon Dunes in 2001 following a stint at Spyglass Hill, a famed course along California’s Monterrey Peninsula with Poa annua and ryegrass playing surfaces. Lewis arrived at Bandon a year later. “There’s no fine fescue school or class,” Johnson says. “It’s on-the-job training.”

On a clear, 70-degree afternoon 52 days before the U.S. Open, Johnson and Lewis are discussing their maintenance practices. They are asked about the daily challenges fine fescue presents. The question is as open as the course they maintain. Johnson and Lewis are both temporarily stumped, a sign they are so focused on their work that it never occurs to them they are doing something abnormal. “It makes it hard to answer that because both of us spent time at Bandon Dunes and this is very similar to that,” Lewis says. Johnson takes another crack at offering an answer. “I guess acreage-wise you would have to get away from a fescue golf course to find something else that compares,” he says. “We are a lot bigger than most average golf courses.”

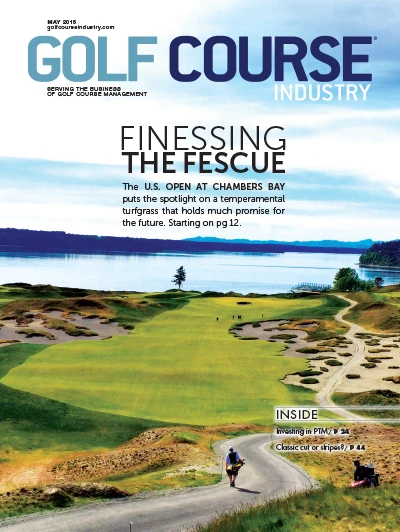

The scope of Chambers Bay is startling. The view from the multi-use trail above the course makes the site appear large enough to fit 54 holes. USGA Green Section director of championship agronomy Darin Bevard made his initial Chambers Bay visit in November. “The first thing that went through my mind was the size of the place, just the acreage involved for maintenance,” he says.

The scope of Chambers Bay is startling. The view from the multi-use trail above the course makes the site appear large enough to fit 54 holes. USGA Green Section director of championship agronomy Darin Bevard made his initial Chambers Bay visit in November. “The first thing that went through my mind was the size of the place, just the acreage involved for maintenance,” he says.

Chambers Bay includes 35 acres of fairways and the tees and greens average 21,041 and 8,700 square feet, respectively. Merion Golf Club, the site of the 2013 U.S. Open, had 18 acres of fairways with average tee and green sizes of 3,000 and 6,000 square feet, respectively. USGA executive director Mike Davis succinctly calls Chambers Bay “a bold site.”

Walk this way

A bold decision made by a politician led to Chambers Bay becoming the first wall-to-wall fescue course to host a U.S. Open. Pierce County purchased the property, which rests along the Puget Sound, in 1992. At the time, 165 million tons of gravel had been mined at the site.

The site also featured large amounts of sand, a valuable commodity in the golf industry. Multiple Pacific Northwest golf course, including the Tom Fazio-designed Aldarra Golf Club in nearby Sammamish, Wash., sit atop sand mined from Chambers Bay. A solid base of sand means good drainage, which increases the design options for golf course architects.

Easy access to sand. Championship course. Stunning scenery. Politicians looking to leave a legacy. Climate with year-round golf opportunities. The success at Bandon Dunes. It’s no wonder Pierce County received proposals from more than 50 golf course architects. The list was trimmed to five finalists, and Robert Trent Jones II unveiled its plans for a links course during an interview on Jan. 20, 2004.

“We explained that the reason why the site was so special was because it had all the ingredients to create a true links experience,” says Jay Blasi, an with RTJII at the time. “First of all, you are in the Pacific Northwest, which is really the only spot in America where you can have true links in terms of the maritime climate. And the site itself was a former sand and gravel mine. A golf architect’s greatest natural resource is sandy soil. The sand in the big pit was a gold mine, and you couple those two things together and you have the opportunity to utilize fescue and get the firm, fast playing conditions.”

“We explained that the reason why the site was so special was because it had all the ingredients to create a true links experience,” says Jay Blasi, an with RTJII at the time. “First of all, you are in the Pacific Northwest, which is really the only spot in America where you can have true links in terms of the maritime climate. And the site itself was a former sand and gravel mine. A golf architect’s greatest natural resource is sandy soil. The sand in the big pit was a gold mine, and you couple those two things together and you have the opportunity to utilize fescue and get the firm, fast playing conditions.”

Lulls in activity are expected when politicians are the developers in a golf course project. Construction at Chambers Bay didn’t begin until the fall of 2005, and earlier in the year Pierce County executive John Ladenburg made what Blasi, who now operates his own architecture firm, calls “the biggest decision” in the creation of Chambers Bay: prohibiting carts. Fine fescue and carts mix as well as dry 100-degree days and bentgrass. Ladenburg sacrificed revenue in the spirit of links golf. A decision to permit carts would have forced RTJII to revamp its design, Blasi says.

On the surface, a wall-to-wall fescue golf course should be an attractive option considering the industry’s increasing emphasis on resource management. For starters, fescue requires less water and fertility than other turfgrass varieties, according to Oregon State turfgrass specialist Alex Kowalewski.

Chris Condon, the superintendent at Tetherow Golf Club, a David McLay Kidd design in Bend, Ore., is maintaining a course with a fine fescue-colonial bentgrass blend on its playing surfaces. When Tetherow, which opened in 2008, was under construction, Condon maintained a bent-Poa course in Bend. He estimates that fine fescue requires half as much water, nitrogen and mowing/labor as bent-Poa. “That’s kind of what I always felt,” Condon says. “You take a course here in town and cut it in half, and that’s what we’re working with.”

|

Swapping ideas So where does an American superintendent exchange information about fine fescue? Chambers Bay’s Josh Lewis has found it at a place where no U.S. Open superintendent has dared to go: Twitter. Lewis has kept his popular @theturfyoda account active as he prepares a course for a major championship. “For me, it’s more about fescue than it is about the U.S. Open with the information I put out there,” Lewis says. “I like to show people different ways of doing things, something that’s crazy outside the box. You don’t have to mow this grass at .095 to get it fast. We can mow it .200 and have greens rolling at 11. It’s just something different. It has really sparked some interesting conversation and friendships.” The pre-Twitter days also included some interesting conversations about fine fescue maintenance. Chambers Bay director of agronomy Eric Johnson was involved in the early grow-ins at Bandon Dunes and he remembers conversations with Jimmy Kidd and the agronomy team at Gleneagles in Scotland. The grow-in process at Bandon Dunes was refined with the construction of each course, and Johnson says the resort’s first superintendent Troy Russell and current director of agronomy Ken Nice were frequently seeking additional information about fine fescue. “Slowly over time connections were built,” Johnson says. Bandon Dunes has hosted five USGA championships since 2006. The USGA has never conducted one its three biggest events – the U.S. Open, U.S. Women’s Open and U.S. Senior Open – on a wall-to-wall fescue course. USGA executive director Mike Davis considers a superintendent “the most important person at the U.S. Open.” The Chambers Bay duo is especially important this year because of the lack of fine fescue knowledge in the U.S. “I have leaned very heavily on Eric Johnson and Josh Lewis,” USGA Green Section director of championship agronomy Darin Bevard says. “Those guys coming from Bandon have a lot of experience with fescue and they have educated me. I have talked to some others about it, but primarily it has been Eric and Josh who have helped me understand it. And to their credit, everything to date that they have predicted would happen in terms of recovery and everything else has certainly happened.” |

Bend, an inland city in the Central Oregon, is 260 miles from Bandon, and temperatures swell past 90 degrees in summer and dip below freezing in winter. Bend receives an average of less than 12 inches of rain per year. Summer can be tricky, and Condon says it’s “one of the grasses you can’t bring back in a couple of days.” Fine fescue, in short, turns brown when the plant is stressed.

“The thing with water is you have to kind of have some realistic expectations,” Kowalewski says. “Perennial ryegrass and fine fescue are two different things. One is like a work truck, one is like a BMW. One is going to look really nice if you fertilize and water it. The fine fescue, on the other hand, in the summertime, if it’s not being watered, it will go brown, but when the rains return in the fall, it will green back up and look really nice.”

Wear tolerance, building seedbanks and repairing divots are other dilemmas posed by fine fescue. Chambers Bay, the regulation layouts at Bandon Dunes, Tetherow, Ballyneal (Colo.) Golf Club and Gamble Sands (Wash.) are among the American courses with some form of fine fescue on fairways and greens. Cart usage is either prohibited or discouraged at most of the above courses. “Traffic is a challenge no matter what type of turf you are maintaining, but this one is probably longer recovery time than anything else,” Lewis says. “You really have to be proactive.”

Chambers Bay limits its mowing to once per week during even mild winters like this past one, and supervisors must regularly educate crew members about preferred driving routes and techniques. “You’re not going to see any tight turns or anything like that,” Lewis says. “Roller damage is a big one. You have to be extra careful around greens. You may not hurt the grass, but you are going to see the tracks.”

Building seedbanks requires rigorous overseeding. Chambers Bay uses red and Chewings fescues on its greens, and the staff overseeded putting surfaces 14 times in 2014, according to Lewis. Extreme caution was displayed during this past winter. The course never closed for an extended period, although play was limited and multiple greens were closed at various times.

“The irony of that is – and there has been a lot of talk about it – most golf courses at that latitude where we would host a U.S. Open, they would just be closed in the wintertime anyway,” Bevard says. “In that climate, it’s unique because you have a lot of weather days where golf can be played and it can be played comfortably, but the grass is growing, so you have a chance to wear the grass out. They have done a great job of limiting play and traffic throughout the golf course, and that helps a ton.”

While green height for the U.S. Open is still being determined, Davis says they should run between 12 and 12.5 on the Stimpmeter. Fairways will be cut at .500.

As far as the divots, there’s no easy solution. They take much longer to heal compared to ones on other turfgrass varieties. “You have to be patient,” Johnson says. “You’re not getting instant gratification of stuff recovering quickly.”

The fescue option

This marks the second straight year the U.S. Open could spark an agronomic debate. Chambers Bay doesn’t feature the history of Pinehurst No. 2, but it’s a walking-only course with a turfgrass variety that plays perhaps faster and firmer than anything ever experienced at a U.S. Open. Fine fescue blades are round, bentgrass blades are flat. Balls skid off fescue while they often stop on bentgrass.

Hard, brown turf covered Chambers Bay when it hosted the 2010 U.S. Amateur, which served as a trial run for the U.S. Open. Firsthand observations and data collected during the tournament resulted in modifications to 10 holes. “We learned a lot about Chambers Bay and its nuances,” Davis says. “We basically had the golf course too firm, even though we tried to take away some of that firmness before stroke play started. We didn’t quite get there – and we essentially flooded the golf course the evening when stroke play ended.” The U.S. Amateur is conducted in August, two months after the U.S. Open and area superintendents say June is a considerably wetter than August in the Seattle-Tacoma region.

Debates about turf removal, irrigation practices and brown turf providing acceptable playing conditions ensued after the 2014 U.S. Open at Pinehurst. Will similar conversations about fine fescue follow this year’s tournament?

“It will certainly raise more awareness with fine fescue, but I think the areas where it can be used and the circumstance under which it can be used my limit it,” Bevard says. “I don’t think it’s going to be a revolution where you see fine fescue all over golf courses, just because of the traffic issue.”

Oregon State started an in-depth fine fescue trial last year and portions of the study will examine wear tolerance. “It seems to be one of the grasses of the future because of its sustainable characteristics,” Kowalewski says.

The financial sustainability of golf facilities could be the biggest barrier to widespread wall-to-wall fescue use. The dreamers, builders and maintainers involved in Chambers Bay gambled by constructing a course where carts are discouraged and brown turf is sometimes encouraged. It’s a combination seldom seen in American golf.

Guy Cipriano is GCI’s assistant editor.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the May 2015 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Advanced Turf Solutions’ Scott Lund expands role

- South Carolina’s Tidewater Golf Club completes renovation project

- SePRO to host webinar on plant growth regulators

- Turfco introduces riding applicator

- From the publisher’s pen: The golf guilt trip

- Bob Farren lands Carolinas GCSA highest honor

- Architect Brian Curley breaks ground on new First Tee venue

- Turfco unveils new fairway topdresser and material handler