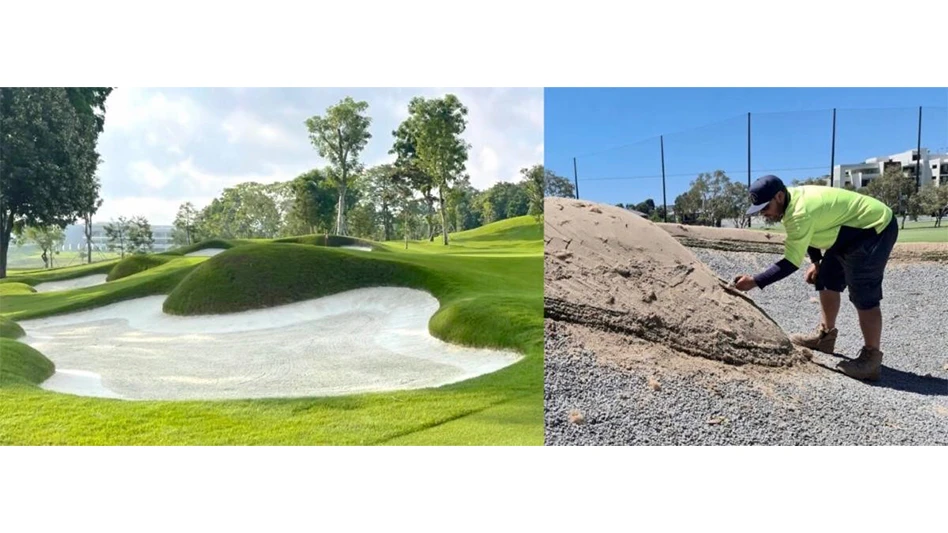

Beyond enhancing a golf course’s aesthetics and imbuing a routing with added challenge for golfers, natural/native areas can prove a help to superintendents battling the bottom line.

Beyond enhancing a golf course’s aesthetics and imbuing a routing with added challenge for golfers, natural/native areas can prove a help to superintendents battling the bottom line.

Naturalized rough areas reduce the total acreage that must be maintained on an ongoing basis, eliminating the need for weekly mowing and reducing water usage, thus cutting overall operating costs and conserving valuable resources that can often be strapped by severe weather conditions such as drought.

Naturalizing portions of a golf course that has severe slopes, are rocky in character or are near water features also greatly reduces a superintendent’s labor and stress levels.

Native areas, often quite pleasing to the eye and bursting with flora and fauna, show golf courses and superintendents to be what they truly are, good neighbors and stewards of the land, respectively.

While native areas are considerably easier to maintain than the general playing surface, any good superintendent realizes you can’t just make a portion of a golf course natural in character and then not pay any attention at all to it. Natural or native areas still need to be maintained to prevent them from quite literally going out of control with unwanted growth, or from invasive plant species and pests that can have damaging effects not only on the natural areas themselves but even, perhaps, the golf course as whole.

The Sagamore Club in Noblesville, Ind., has nearly 77 acres of natural areas that were seeded with a dunes mix that was predominately fine fescue, says Gary Myers, CGCS.Myers claims native areas are really no different than taking care of primary rough. The only difference is that the native areas are not irrigated and are not fertilized, which, he says, results in a significant cost savings.

“We still treat all 77 acres with a pre-emergent in the spring. We also apply post-emergent applications two to three times throughout the year. The main difference in controlling native area weeds compared to primary rough is the type of weeds you are trying to control.”

Myers’ biggest weed problems in native areas are thistle, milkweed and annual grasses, such as foxtail.

Myers’ biggest weed problems in native areas are thistle, milkweed and annual grasses, such as foxtail.

“We are trying many different approaches this upcoming year in trying to control foxtail. We will be applying a barricade in the fall and coming back in the spring with a second application to hopefully help control this grass. This past year we tried to control foxtail with a post-emergent product that worked but was costly and you could still see the decaying plant in the native areas.”

Myers sprays all liquids in his course’s native areas with two sprayers. “Even with all this effort, I believe that the native areas are not only important to the playability and toughness of the golf course but do save on money,” he says.

Jim Van Herwynen, CGCS, South Hills Country Club in Franksville, Wis., says of his course’s 45 acres of native area, “Anyone who says they are maintenance free is a liar. They do require attention yearly for weed encroachment, noxious weeds, such as Canada thistle and garlic mustard, and also buckthorn.”

Yet, he reports, natural areas “are a cost savings because we have minimal inputs – one or two herbicide applications per year and fuel for cutting them down to about 4 to 6 inches in the late fall. The fuel savings of not cutting them once a week if we were to cut them as rough is substantial.”

He adds, “We typically do not fertilize them on an annual basis due to reduced budget numbers, however the edges along our rough do get fertilized once or twice a year and that probably gets in about 20 to 25 feet. We apply any leftover fertilizer at the end of the year to the areas that appear to be weaker than others.”

Van Herwynen shaves the areas down once a year in late fall with one employee using a brush cutter and tractor combo for about a week. “Weed control is essential as it can get out of control very quickly,” he says. “We have had problems with Canada thistle, so you have to get them sprayed with an herbicide once the thistles pop. We have had a few ant hills form in them as well that we try to bait periodically.”

Primland Resort’s Highland Course was built on top of a ridge in the Blueridge Mountains area of southwestern Virginia in Stuart and has several significantly steep slopes. Creating native areas was an easy way to minimize mowing these areas, according to superintendent Brian Kearns.

“These areas are fairly difficult to maintain, but there is a cost savings from a fuel and fertilizer perspective,” he says.

Kearns and his staff mow the natural areas once a year in September or October.

“One half pound of nitrogen is put out in these areas per year along with a crabgrass pre-emergent herbicide,” he says. “We use several post herbicides for the many broadleaves and saplings that are constantly popping up. We also use weedeaters, brush blades, and even hand pull the many weeds in these areas. We spot treat with insecticides to fight grub, cutworm, and chinch bug damage. We have some re-seeding to do each year due to insect damage.”

Kearns believes there are some misconceptions pertaining to natural areas.

“Our goal is to keep these areas having the tall, wispy, clean look, while keeping them lean and golfer-friendly (tall but thin enough to find a golf ball),” he says. “We are still trying to achieve this goal. Native areas are constantly trying to re-forest. Weeds and insects have made our task extremely difficult. We treat a few of these areas preventatively, but we mostly scout and treat curatively.”

Maintaining natural areas is not labor intensive, Kearns adds.

“We are not using a lot of labor mowing, he says. “Instead, we are using about half of the labor removing weeds, scouting and treating insects. Every year something new comes along and we find ourselves scratching our heads once again. We are constantly learning and thinking of new methods of maintaining these ‘low maintenance areas.’”

Glendon Junkin, superintendent at Turtle Point Yacht and Country Club in Killen Ala., has about 35 acres of natural area on his course.

“We decided to plant many of the areas that were out of play in fescue and let it go natural,” Junkin says. “This helped save money, gave some character to many of the holes, and provided wild life habitat for our Audubon certification. I Bush Hog the areas every September. That’s it. I have 35 acres less to mow per week now than I did before, so there is fertilizer savings, labor savings, and fuel savings.”

Mark Cote, superintendent at the Pete Dye River Course in Radford, Va., mows his native areas two times a year, in the spring and fall. “These areas also have to be treated with broadleaf weed control so that they are uniform and serve an aesthetic purpose as well as a design feature,” Cote says. “The border/out of bounds areas are mowed three to four times a year in order to keep the woody plants from invading from the wood line. Our natural areas along the riverbank are mostly manually maintained throughout the year to keep from becoming overgrown and thus losing their ability to filter any runoff.”

Scott Roche, superintendent at Newport National Golf Club in Middleton, R.I., say his course’s ownership and management views natural areas as vital to the facility.

“The areas are quite important to the overall aesthetics,” Roche says. “Our golf course is wide open and flat without many trees, so they are a major feature.”

He says maintenance practices in the native areas varies from year to year.

“Weeds are our biggest challenge and require mechanical removal and spot chemical application,” Roche says. “If there were nothing done to maintain them, they would be cost saving. Natural areas are only as difficult to maintain as the budget allows them to be.”

Roche mows Newport National’s natural areas each fall and does not fertilize the areas. “We keep natural area margins away from known ‘landing areas’ as to not slow play,” he says. “I would recommend to anyone looking to create naturalized areas to choose a seeding rate carefully and use entophyte-enhanced seed if possible.”

He adds, “Natural areas may not be the cost saving areas that they are perceived to be. And the phrase ‘naturalized area’ can mean different things to different people. Every club is different and every budget is different, so depending on budget/labor and golfer expectations, they can be as cheap or expensive as one wants them to be to maintain.”

What about burning as a means to manage natural areas?

The practice was once viewed as a low-cost, effective way to control such areas and is still practiced by some. Burning is often initiated during spring as a way to control weeds and remove excessive organic material from grassland areas. Fire can stimulate seed germination, warm the soil and make nutrients more available.

Of course, the use of fire to control native areas must be approached with caution and planning. Burning may not be allowed in certain areas of the country and most municipalities require permits to burn, which may be difficult to obtain if the course is located even somewhat close to residential or commercial property.

“A controlled burn could be an option,” Roche says. “One would still need to quantify the cost/benefit to this practice in addition to adhering to the local laws.”

Burning can help, Cote says, but it also may be an opportunity for weeds to come in. “It also must be done carefully and in coordination with local authorities, obviously,” he adds

Van Herwynen would like to use fire to control his course’s native areas but can’t. “Burning would definitely be the way to go in the fall due to the tremendous biomass that is produced yearly,” he says. “But we cannot burn because we are in the city limits and surrounded by homes.”

Kearns also considers burning an option, but probably not at Primland.

“Burning is a good solution in assisting with unwanted species,” he says. “Unfortunately, our resort is on 12,000 acres of forest and burning scares me a bit. The wind always blows on the mountain top.”

Establishing native areas on a new or existing course can have significant benefits, but like issues pertaining to most turfgrass management it is not cut-and-dried.

The misconception about native areas is that they require little to no yearly maintenance, Myers says. “If you do not keep up with weed control, native areas can soon become out of control,” he says. “They then become more of a chore to have them looking kept. A lot depends on the expectations of your membership. The other misconception is that it takes little money to maintain once established. Again this depends on your membership. But we spend about $7,000 to $10,000 year maintaining our native areas. Still, there is a considerable savings considering if you had to spray, mow and irrigate the 77 naturalized acres we have.” GCI

John Torsiello is a Torington, Conn.-based freelance writer.

WANT MORE?

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the December 2010 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Bloom Golf Partners adds HR expert

- Seeking sustainability in Vietnam

- Kerns featured in Envu root diseases webinar

- Toro continues support of National Mayor’s Challenge for Water Conservation

- A different kind of long distance

- Golf Construction Conversations: Stephen Hope

- EnP welcomes new sales manager

- DLF opening centers in Oregon, Ontario