The GCN staff presented the 2006 Golf Course News Builder Excellence Awards at the Golf Course Builders Association of America’s awards dinner, which occurred in conjunction with the Golf Industry Show in Atlanta. This year, four awards were presented. Landscapes Unlimited won the Creative Award for best new construction with Laughlin Ranch Golf Club in Bullhead City, Ariz. Ryangolf won the Heritage Award for best reconstruction with Boca West Country Club’s Course No. 2 in Boca Raton, Fla. McDonald & Sons won the Legacy Award for best renovation with Hermitage Country Club’s Manakin Course in Manakin-Sabot, Va. And Mid-America Golf and Landscape won the Affinity Award for best environmental project with Lambert’s Point Golf Course in Norfolk, Va. The following four articles are about these award-winning projects.

The highest point in Norfolk, Va., is Lambert’s Point Golf Club, a nine-hole, Scottish-links-style course that offers golfers scenic views of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, the Norfolk skyline and the Newport News shipyard.

|

|

Yet this course might never have been built. The 53-acre site was a dump containing a pile of unregulated trash that accumulated throughout the years. Closed in the 1970s, the ugly, dirty lot was vacant for almost 30 years and had no value to the community. It took a team with vision, expertise and the desire to overcome the challenges needed to turn a landfill into a golf course. It was Mid-America Golf and Landscape’s first landfill project.

“That’s part of what made the project appealing to us,” says Mid-America president Rick Boylan. “We believe this proactive approach of turning landfills into desirable, community-friendly space is a growing trend. We also wanted to expand our operations in the East and work with Lester George of George Golf Design.”

The third component of the team was the city of Norfolk. Chris Chambers, a design engineer with the department of public works was the project manager and city representative. Also on site throughout construction was the course’s project manager, Mike Fentress, who now is head PGA professional and general manager for Lambert’s Point.

Originally, the city determined a golf course would be a good use of the land and worked with an individual who wanted to lease and develop the site. After three years with no progress, Chambers addressed the situation because the project became extensive and detailed and had considerable surprises.

“Brownfield doesn’t even begin to describe this site when we started,” George says. “It took as much thinking as any project we’d ever done. The city was forthright in what they did and didn’t want environmentally.”

Additionally, Old Dominion University, which is in Norfolk, was involved with the development of the golf facility because it serves as the home course for the school’s golf teams. A 6,000-square-foot clubhouse anchors the facility; along with a 4,200-square-foot, bilevel, heated and lighted driving range; a golf learning center; and a short-game practice center complex.

As construction started, the development team discovered grades had changed since the site was last mapped. Some topography had good cover material over the landfill, while other areas had the bare minimum of cap material. A separate contract confirmed and re-established the required cover material. Preserving the cap was a key part of the project.

“We couldn’t cut because we’d break the cap, and trying to fill the sides would just make them steeper,” George says. “It was an exercise in two dimensions. We had to build up, and then we could go down from there. We worked to get variety on the course and address safety issues because we couldn’t plant trees because of the cap.

|

|

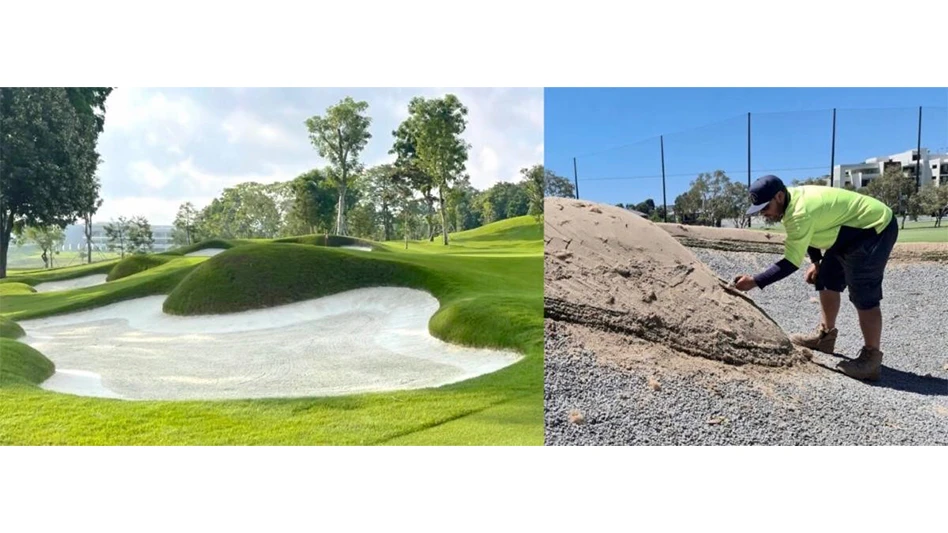

“The design required moving a lot of dirt,” he adds. “Even the underground installations for drainage and irrigation needed to be coordinated and monitored to prevent breaking the cap. Beyond that, we put in many bunkers, added undulations to the greens and sunk the tees down within mounds.”

The extensive fill created more challenges for Mid-America, which had seven months from mobilization to demobilization.

Mid-America’s commitment set the tone that carried the team for the rest of the project.

“The entire team had a great working relationship, making it an interactive decision process when conditions required some modifications of the original layout, such as fairway sloping, bunker placement or undulations,” Fentress says. “All those adjustments make the course more playable, and ultimately, easier for the superintendent to maintain.”

Getting to and fro

The awkward shape of the property boundary presented a challenge circulating construction crews and equipment. A 40-foot-wide channel separated the property into two halves.

“Traffic had to go through the [Hampton Road Sewer District] sewage treatment site, which is gated and guarded,” Boylan says. “We had to have an armed guard check the trucks going in and out of the site. That included more than 100,000 yards of fill material, the gravel, sand for the bunkers, concrete for the cart paths and almost 32 acres of sod, as well as each piece of equipment moved through the site.”

By the middle of the project, there were as many as six contractors working on the course, infrastructure and building facilities. HRSD also had its material moved out as part of its day-to-day activities. As the main contractor on site, Mid-America took on much of the coordination responsibility, interacting with Chambers to keep everything moving forward.

|

At A Glance |

|

Location: Norfolk, Va. |

Additionally, Mid-America needed to be sensitive when dealing with water on three sides of the project.

“The property elevation from the highest point to the water’s edge had huge potential for run off,” Grego says. “Heavy rains during the summer of 2004 added to the challenge. It took a number of diversionary measures and constant inspection to meet all required codes. Vegetative buffers around the edges of the property were enhanced to control erosion.”

Because the course parallels a sewage treatment plant, a netting system was essential to keep nondegradable items, such as golf balls, from the containment area where waste is broken down into a fertilizer by-product, Boylan says.

In the end

Chambers says the finished product is a treasure for the city that could only have been achieved by all parties working together toward a common goal.

“There was a minimum amount of project variation and a lack of change orders,” he says. “It came in on time and within budget and is something to be enjoyed for many years.”

Lambert’s Point is an example of how wasteland can be turned into something useful.

“There are sensitive environmental issues to consider, but an unused piece of property that’s close to a populated area is a resource we’d like to think more people would be developing,” Boylan says. GCN

Steve and Suz Trusty are freelance writers based in Council Bluffs, Iowa. They can be reached at suz@trusty.bz.

Explore the March 2006 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Toro continues support of National Mayor’s Challenge for Water Conservation

- A different kind of long distance

- Golf Construction Conversations: Stephen Hope

- EnP welcomes new sales manager

- DLF opening centers in Oregon, Ontario

- Buffalo Turbine unveils battery-powered debris blower

- Beyond the Page 66: Keep looking up

- SePRO hires new technical specialist