Managing the modern putting green for demand ing golfers is as much art as it is a science. Increasingly, performance expectations are challenging superintendents’ skills, pushing biological boundaries and stretching budgets. What was acceptable performance a few years ago seems a memory of a bygone era because even the high-handicap golfer expects championship conditions.

The issue of green speed is here to stay, and the challenges intensify with the introduction of new types of grasses that allow for lower mowing heights. Course design and new mower technology are among other new developments that impact green speed.

And, equally important is the information about green speed that needs to be communicated to golfers effectively. As much as the topic is discussed, it seems that golfers understand less about what makes greens faster or slower, or even to what extent they can tell the difference between a green that is stimping at 8.5 feet or one that rolls at 9.5 feet.

Green speed is a range

Despite printing several articles in the club newsletter detailing the agronomic issues of maintaining putting greens and explaining what Stimpmeter numbers mean, green speed continues to be an issue among the membership at Crystal Downs Country Club in Frankfort, Mich., according to superintendent Michael Morris, CGCS.

Working closely with his greens committee chairman, David Rosenberger, Morris concluded that the  first step to address the topic was to determine the range of green speeds at his course. That could be expected throughout the day on a daily basis. After addressing this issue, Morris would be able to present the appropriate green speed for Crystal Downs to the greens committee and membership.

first step to address the topic was to determine the range of green speeds at his course. That could be expected throughout the day on a daily basis. After addressing this issue, Morris would be able to present the appropriate green speed for Crystal Downs to the greens committee and membership.

To conduct his research, Morris measured the speed of two greens with a Stimpmeter everyday from Memorial Day to Labor Day in 2001 and 2002. This also was done twice a day, once in the morning and again in the afternoon.

Morris’ next step was to survey 20 golfers who represented a cross section of the membership to determine their satisfaction with the course’s green speed. They were asked four questions about their perception of the greens. During the season, Morris received 260 responses from them. At the same time, Morris and his staff looked for ways to fine tune maintenance practices to minimize considerable differences in green speed.

The results of this research produced surprises for Morris.

"The old wives’ tale that greens are faster in the afternoon as they dry out was almost never the case on our course," he says. "The greens were almost always slower in the afternoon as the grass grew and the putting surface received traffic. We also found that green speed decreased drastically during the day if we did not get a good cut in the morning. When we mowed the green twice—once before the morning measurement and again before the afternoon measurement—we would see a noticeable increase in speed."

The average decline of speed throughout the day was about 6 inches but could be as great as 18 inches. Morris determined that a green speed of 9.5 feet to 10.5 feet was a realistic target. Golfer surveys indicated speeds below 9.5 consistently were too slow, while speeds approaching 11 consistently were too fast.

"What we learned regarding our maintenance practices is that they are very specific to our golf course, resources, golfers and greens," he says. "Every golf course searching for the most appropriate green speed will likely encounter a different set of variables. We discovered that a superintendent could indeed determine a green-speed range that is manageable throughout the season and satisfies the golfers at his course."

Designed for speed

As Morris’ example demonstrates, golfers judge many superintendents on green speed. Clearly, the pursuit of fast greens increases course maintenance budgets to provide firm, true and fast surfaces. But there should be consideration given to the influence this trend will have on putting green design.

"Simply put, fast greens will need to be flatter or will have to be significantly larger in size to allow the ball to come to rest near the cup," says Cornell University’s Frank S. Rossi, Ph.D. "While there are no strict provisions for green speed and cupping area in the Rules of golf, there is some acceptance that fast greens with severe contours will not permit the ball to come to rest near the cup. Subtly, we have been observing this phenomenon the last few years at the U.S. Open."

Consider the 18th green at Southern Hills Country Club in Tulsa, Okla., site of the 2001 U.S. Open Championship. Much was made of the severe slope that was questioned by players during the practice rounds for being too fast, penalizing a good shot as balls rolled off the putting surface. Here was a case in which the design conflicted with agronomics.

John Szylinski, the golf course superintendent at Southern Hills, was focused on providing the highest quality putting surfaces with the new generation bentgrasses installed during the renovation of his course. These bentgrasses were bred for high shoot density that permits and requires low mowing heights. The consequence was that green contours maintained at normal green speeds would be acceptable, yet speeds generated with the new bentgrasses wreaked havoc among players and officials.

"When emeritus professor Joe Duich of Penn State University developed the new generation high shoot density bentgrasses, he clearly had green speed in mind," Rossi says. "The same design for speed was true for the breeders of ultradwarf Bermudagrasses. It seems the breeders had it right. The new generation grasses that provide fast greens are being planted on 90 percent of the new courses. They have become the standard."

Now that fast greens are the standard on new courses, mechanical and chemical technology should be available to maintain the surfaces. New mowers able to cut lower, and growth regulators that enhance plant density and slow growth are keys to providing speed.

Architects have responded to this trend by increasing the putting area but keeping the contours, although many have chosen less severe undulation. This is easier in new construction, but what’s happening with renovating old courses?

When greens were renovated and new grasses were planted at Apawomis Country Club in Rye, N.Y., there wasn’t enough cupping room. Some greens had to be rebuilt because they were too small and too fast for the design.

"Apawomis removed some of the severe undulations but did not plant the highest shoot density grasses," Rossi says. "They opted for L-93, a notch below the Penn A and G series in shoot density, mixed with some experimental greens-type annual bluegrass from professor Dave Huff’s breeding program at Penn State. The superintendent told me the greens look great and have a consistent appearance with the existing greens that were not renovated."

It seems that while green speed is important and can influence design, aesthetics can also play a role. The visual consistency appreciated at Apawomis is an example. It’s possible fast greens aren’t the only things that make a round of golf pleasurable.

"We need different grasses," course architect Rees Jones says. "Breeders are taking away my ability to add contours to my designs. The grasses need to be cut so low, I have to flatten my thinking."

Jones is a proponent of traditional shoot density bentgrass species such as Penncross and Pennlinks. These grasses can be maintained at mowing heights that produce more average green speeds in the 8-foot to 10-foot range.

Flat green soils

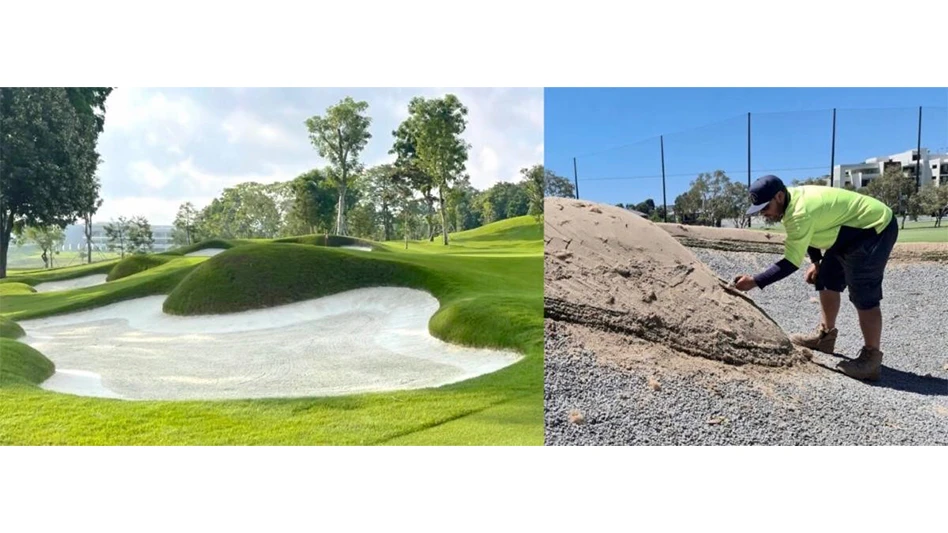

There are below-ground consequences of putting green design that will influence root-zone selection and performance. Flat greens place a greater emphasis on subsurface drainage. This compares to older undulating greens built with native soils that emphasized surface drainage. The advent of sand dominated root zones, such as the United States Golf Association specifications for putting green construction allows for greens to be flat and indirectly fast.

"Flat greens can reduce the need for amendments that might aid in water holding," Rossi says. "Amendments have been shown to be of particular importance to water management of undulating surfaces, as peaks of severe slopes will drain more rapidly. Amending the sands with organic materials such as peat or compost has been shown to enhance a uniform moisture level throughout an undulating surface."

Research by professor Ed McCoy of Ohio State University investigated the effect of root-zone profile and putting-green slope on internal drainage.

"The results of his study concluded that the USGA method for green construction that includes a gravel layer below the sand root zone permits more rapid and complete drainage," Rossi says. "Furthermore, undulating surfaces built to USGA specifications performed better than the straight sand California specifications."

Root zones of flatter greens might reduce cost by performing well with less organic amendments, which permit more uniform drainage to enhance soil aeration.

"Theoretically, based on cupping area, flat greens could be smaller in size, depending on the amount of traffic expected, and require less total inputs," Rossi says.

Is speed sustainable?

The technology is available to most golf courses to provide fast greens. Biological advancements with high-shoot-density bentgrasses and ultradwarf Bermudagrasses are where it begins. Conditioning required to maximize the performance of these grasses is available with mowers, top dressing equipment, rollers, etc. A lingering question is: If greens are designed for interest with contouring and maintained for speed, will the result be an enjoyable round for the average player?

"Lost in the discussion of speed are the functional aspects of grasses and soils that would allow reduced water and pesticide use," Rossi says. "Disease resistance and drought tolerance of these grasses appear to have been an afterthought to the breeders. Obsession with high permeability root zones that allow rapid drainage assumes a plentiful supply of water. As we begin to hold designers to higher standards for environmentally friendly designs not just focused on speed, why shouldn’t we hold the breeders and soils scientists accountable as well?"

Manage for speed

The next generation of bentgrasses offers improvements in shoot density, heat tolerance and possibly some new challenges with recuperative ability. The bottom line is that many new bentgrasses offer the ability to tolerate low mowing heights while maintaining acceptable quality. Many research studies suggested the relationship between low mowing and ball-roll distance (Stimpmeter measurements), meaning the lower the mowing height, the greater the ball roll distance. Rossi’s research at Cornell University demonstrated that performance of specific varieties at heights as low as 0.080 inches can produce ball roll distances of more than 14 feet.

"Our results indicated that up to 3.5 feet can be gained in ball roll distance by reducing cutting height from 0.125 to 0.095 inches," Rossi says. "Yet, it is important to note that except for Penn G-1, no other cultivars were able to maintain acceptable quality at the close cutting height under traffic treatments.

"Furthermore, as cutting heights were lowered to 0.125 inches and below, many of our plots exhibited significant reductions in surface density," he says. "Plots established at the recommended seed rate of 0.5 had a 25 percent to 50 percent greater incidence of algae compared to high seed rate plots, especially for the more prostrate growth habit cultivar Penncross. As cutting heights were increased above 0.125 inches in early fall, algae was not evident. In addition, there was a surprising increase in the incidence of take-all patch associated with the low seed rate plots."

Just as an entire industry might have been established to support the care of Penncross, it appears the management of the new bentgrasses, especially the high-shoot-density varieties in the Penn A and G series, will require different management. A study conducted at the University of Wisconsin investigated the amount of top dressing material picked up by mowers. Almost 4 percent of the applied top dressing was collected in the first mowing for Penn A-4, with about 3 percent for G-2. Penncross and annual bluegrass resulted in 2.5 and 1.5 percent, respectively.

Many top superintendents who currently manage the Penn A and G series say no increased maintenance is required.

"This should be expected at the top clubs with adequate maintenance budgets that already are aggressively top dressing, liquid feeding and maintaining superior equipment," Rossi says. "However, these grasses are not for clubs that cannot realistically support a high level of care. Leading the next level of bentgrasses are Crenshaw, L-93, SR1119, Cato and Southshore, which offer many advantages of the high-shoot-density varieties without much of the additional care. These grasses all perform well at mowing heights at or below 0.125 inches and offer myriad of disease and environmental stress tolerance."

It’s the mowers

But Morris offers a different point to Rossi’s contention that new grasses have a major influence on green speed. He asserts that green speeds should be managed—either speeded up or slowed down—with grass type, green contours and golfer expectations in mind. At Crystal Downs, it became clear to him during his investigations how much cultural practices influence green speed.

"There is a new course just down the street from us that is facing the same issues we do with regard to green speed," Morris says. "It’s a world class facility with A-4 bentgrass greens. In a comparative study, we found that their green speeds exhibited the same degree of fluctuation as ours did day to day. Though their greens are maintained 6 inches to 1 foot faster than ours, the design of the greens accommodates that speed. If the greens at that course are maintained any faster, golfers sometimes begin to complain that they are too fast for the design.

"The issue of green speed is not about the grass; it’s about how you take care of it," he says. "To manage our greens at a speed of 9.5 to 10.5 feet, we looked at mower set-up, rolling frequency, irrigation, fertilization, use of plant growth regulators and top dressing. Our goal for each of these elements was consistency. We tried to eliminate anything that might cause a drastic change in green speed."

Morris found the most important factor to maintaining green speed was mower set-up.

"Once we determined the appropriate mowing height for our Poa annua greens, we found that a daily check of the height of cut and quality of cut is critical," he says. "The greatest swings in speed we recorded could be traced directly to a mower that was not sharp or not properly adjusted. As a result of our study, our mechanic has developed an intensive mower set-up and reel grinding schedule for our greens mowers."

Morris also found green speed fluctuates.

"The results of our efforts proved to me that green speed is not a number, but a range," he says. "Maintaining a 1-foot range is a good target. Our data told us that if we can do this 60 (percent) to 70 percent of the time, that’s excellent. We also gathered weather data every one-half hour throughout the day of our survey period. Precipitation was the greatest influential factor, not humidity or temperature. If we had one-half inch of rain, the next day our green speed would drop 6 inches."

The price of speed

Frequent low mowing has been shown to be stressful to turf. One study that looked at Penncross and Crenshaw creeping bentgrass mowed at 0.125 inches and 0.157 inches. The results showed that mowing at 0.125 inches regardless of the bentgrass variety produced weaker, stressed plants. The weaker plants were the result of an increase in energy usage required from close mowing and reduced energy production from photosynthesis, which is naturally lower under high temperatures. The study concluded that increasing mowing height by 0.03 inches significantly increased stress tolerance.

Other studies have shown increased disease associated with low mowing heights. For example, researchers found that annual bluegrass mowed at 0.157 inches had 40 percent less summer patch than the same annual bluegrass mowed at 0.125 inches.

"Clearly, the high price of speed can be devastating and costly to maintain with increased disease pressure requiring additional fungicide inputs," Rossi says.

Telling the difference

With the amount of time, effort and money being spent to maximize green speed, golfers should be able to discern subtle differences in green speeds. Can a golfer tell the difference between a 5-foot, 6-inch green and a 6-foot, 6-inch green any better or worse than the difference between a 9-foot, 6-inch green and a 10-foot, 6-inch green?

Researchers at Michigan State University set up several putting-green areas with a variety of speeds. Golfers of various handicaps were asked to putt on the greens and choose the faster green. In general, the golfers in the study weren’t able to discern a difference in green speed less than 6 inches. Conversely, golfers were able to detect differences of 12 inches. Greater than 80 percent chose the faster green when the difference was between 7-feet, 10-inches and 8-feet, 10-inches, whereas 68 percent could tell the faster green between 8-feet, 6-inches and 9-feet, 6-inches

"Green speed differences of 6 inches or less across a golf course is a sign of consistency," Rossi says. "Also, green speed changes of 1 foot have less chance of being noticed by the average golfer once speeds get above 9 feet. Therefore, there could be other psychological factors involved in the golfers assessment of green speed. In the end, the pursuit of speed is easy, yet complex, with a variety of biological, physical and psychological factors at play." GCN

David Wolff is a contributing editor based in Watertown, Wis. He can be reached at dgwolff@charter.net.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the June 2004 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Toro continues support of National Mayor’s Challenge for Water Conservation

- A different kind of long distance

- Golf Construction Conversations: Stephen Hope

- EnP welcomes new sales manager

- DLF opening centers in Oregon, Ontario

- Buffalo Turbine unveils battery-powered debris blower

- Beyond the Page 66: Keep looking up

- SePRO hires new technical specialist