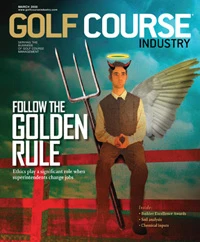

The golf course management industry is a close-knit business. Therefore, when it comes to getting a new job, leaving one, or firing or hiring golf course superintendents, the Golden Rule applies.

“What we’re trying to do on a national level is keep this from being a cutthroat profession,” says Scott Woodhead, the senior manager of governance and member standards for the GCSAA. “Have respect and integrity for your peers. Treat them like you’d like to be treated.”

In that regard, the GCSAA has a code of ethics and professional conduct guidelines. The code of ethics is a governing document established in the GCSAA bylaws for its members that outlines the highest professional standards. However, they’re standards, not laws.

Anyone has the right to work, but the GCSAA discourages applying for a job that hasn’t been posted, for example.

“If that member who’s seeking employment does so in such a way that he or she is making slanderous or inflammatory remarks, it can be deemed a violation of the code of ethics,” Woodhead says. “That’s something that can be taken to court. But unless there’s defamation of character that has occurred in seeking employment, then it’s not a violation of our code of ethics. That basically keeps everyone from breaking the law in terms of seeking employment.”

But the code doesn’t come into play the majority of time, Woodhead says.

More nebulous is when one superintendent visits another’s course as a consultant or when looking for a job.

“The first statement under the professional conduct guidelines is that a member should always contact the superintendent regardless of the intention of the visit,” Woodhead says. “That covers everything from looking for a job to getting a free round of golf.”

And applications for employment should be tendered only if the current superintendent is aware of it.

“We won’t advertise a job opening for an employer until we have notification the current superintendent has been told his job is being advertised,” Woodhead says.

It’s not against the law to visit a course without prior notification, and being approached by an employer and asked to visit a course and give an opinion isn’t a violation of the code of ethics, Woodhead says.

“But the GCSAA doesn’t condone that sort of behavior,” he says.

If an employer contacts a potential candidate, Woodhead says that person should call the current superintendent to let him know that he has been contacted about his job.

“Those are the types of things we can’t enforce with sanctions, but we’re tying to get our members to abide by the guidelines,” he says. “Would my actions meet the approval of my peers? If what I’m doing is on the up and up, it shouldn’t matter if the next guy behind me comes in and does the exact same thing.”

Woodhead says if a superintendent tells the GCSAA a consultant came onto his grounds without previous contact, the organization will write a letter with a copy of the guidelines and ask the consultant to review the professional conduct guidelines and abide by them.

“We’re not a union,” Woodhead says. “We can’t guarantee a job. We don’t have any powers to prevent anyone from doing anything other than to provide them what we see as a professional way of doing business. If it’s illegal, we take similar action to a defamation suit, if it got to that point. Otherwise, it’s a matter of helping the superintendent find that next opportunity and sometimes going to the person who’s doing the incorrect action and getting them to do the right thing going forward.”

Get it in writing

Gary Reeve, a partner at the law firm Kennedy Reeve & Knoll in Columbus, Ohio, is a certified specialist in labor employment law. He says superintendents are like any other employee and can be fired for almost any reason at all.

“As long as they don’t have a contract or union affiliation, they are at-will employees,” Reeve says.

That means they can’t be fired for age, race, gender, disability or national origin, and depending on the size of the staff (if there are more than 50 employees), the Family Medical Leave Act.

“At-will employment works both ways,” Reeve says. “An at-will employee can up and quit, and there’s no legal recourse.”

For a superintendent to have a contract dispute, the contract must specify a duration of time of employment, Reeve says.

“It can’t be an offer letter that details compensation,” he says. “That’s not an employment contract. It has to have a duration of time in it. If it says June of 2007 to June of 2008, and 60 days we’ll notify if we wish to renew, then we’re talking about a contract of duration.”

The GCSAA would like for its members to have duration contracts, but it doesn’t happen nearly as often as it does for general managers or head pros in the industry. Lyne Tumlinson, director of career services at the GCSAA, says her unofficial research shows that about 25 percent of GCSAA Class A members have a contract for duration compared to almost 75 percent for general managers or pros.

“A lot of superintendents don’t think to ask for one,” she says. “I wish a whole lot more had contracts that stipulate a time.”

The right fit

Contracts aside, the most important thing when hiring a superintendent is quantifying the facility’s needs, Tumlinson says.

“What’s good for Augusta might not be good for your facility,” she says. “Look at a marketing plan, strategic direction and the maintenance standards at your facility. You need to have the perfect person for your golf facility. That might mean looking through hundreds of resumes, and it might not be a person with a big name.”

Yet, superintendents should have their own career goals.

“Being at a high-profile club might not be right for you,” Tumlinson says. “When I help superintendents write cover letters and resumes, I ask them to check and see what challenges are there at the job and find the challenges they’ve faced before and how they fit.”

Making a change

Ken Mangum, the director of golf courses and grounds at the Atlanta Athletic Club, says it’s been his experience that friends in the industry can help with a job search.

“When I was hired, the general managers were friends,” he says. “They had someone call me so I could call them so he could say he didn’t call me. The professional thing to do is have the general manager call the other general manager and ask if he has any objections. The correct protocol would be for someone at one club to contact someone at the other club.”

When employees leave, the hope is that everyone keeps a professional attitude.

“Everyone is trying to improve themselves,” Mangum says. “You might not want them to go, but how can you hold them back? How can you be angry at them for looking to get a better job?”

But firing is an entirely different situation.

“How do people get fired?” Mangum asks. “The three top reasons would be: One person got in power and didn’t like someone, and one person got rid of somebody – you see that a lot. Second, someone says, ‘We want to go to the next level.’ They perceive the person they have can’t take them there, when in fact they don’t know what level they’re at. Third is when a new general manager comes in and wants to bring in his own people. That’s OK as long as he gives a guy a chance for a couple of years to show what he can do. Many times, the guy doesn’t get that. They don’t get the full benefit of the doubt.”

Mangum has seen a lot of bad blood result from firings.

“You find out how unprofessional people are,” he says. “I saw a situation in which a single owner hired a guy, and he was set to go to work on Tuesday, and the owner hadn’t told the old person. The new guy called the old guy on Friday to tell him he’d be there, and the old guy didn’t know he was gone.”

It’s a shame when a club decides it wants a new set of eyes without telling an employee about current expectations, Mangum says.

“A guy has given a club 30 years, and he had to leave after 30 years without fond memories of the club he’s given his life to – without a single written documentation saying, ‘You need to do this or that.’ They don’t sit a person down and say, ‘We don’t like this or that.’ If I’m not doing something, and I don’t know it, how do I fix it?”

Consultants

Another scary aspect about the business is the advent of consultants, Mangum says.

“Many times clubs will bring someone in to do their dirty work,” he says. “Unfortunately, the clubs bring in outside consultants and decisions are made. Is that coincidence or by plan? Everyone has to draw their own conclusions. When you walk into a meeting, and there’s a consultant there, and you had no prior knowledge of it, you better get your resume ready.”

A consultant’s job can be easy because he can point out flaws, then leave.

“You can go into any golf course on any given day and find things that aren’t done,” Mangum says. “Is it a leadership issue? Is it a budget issue? What’s the real problem?”

Instead of hiring a consultant, Mangum prescribes bringing in friends and associates for their advice.

“If you’re proactive, the chances of bringing in a consultant are less,” he says. “Consultants can be perceived as a person who can make problems go away. You always have to look at the track record of consultants. You need to do some reference checking and follow up on them. You’re assuming the consultant has a proven track record in the area, the business, longevity. You are assuming a lot of things.”

One also can take advantage of free advice from the USGA’s Turf Advisory Service.

“They see many golf courses in your area,” Mangum says. “They’re regional, and the USGA is respected by people in golf. They aren’t selling anything. They make no money on outside products and equipment. They’re not biased, and they provide a lot of information. And they aren’t there to bury the hatchet in somebody. They’re there to help.”

Randy Nichols worked at Cherokee Town and Country Club in Dunwoody, Ga., for 27 years and now has his own consulting business. He agrees with Mangum that employees need to understand the expectations of employers.

“If someone does it wrong the first time, I feel like it’s my fault that I haven’t told them exactly what my expectations were,” Nichols says. “I’d sit him down and give him 90 days.”

As a consultant, Nichols says he would never go on a property without first telling the superintendent.

“I tell them right up front, if you don’t want me there, I won’t be there,” he says. “I try to help superintendents. I’m not there to fire someone. It’s not my ambition to fire someone. I’m on the side of the superintendent. I’m there to help him keep his job.”

On the up and up

Tommy Witt, CGCS, director of golf course operations at Northmoor Country Club in Chicago, says there are many superintendents of noble character and integrity who will always try to do the right thing when it comes to pursuing a job.

“And likewise, there will be others who aren’t as committed to fairness, if you will, and might try to prosper at the detriment of others,” he says.

The business isn’t as bad as many other professions in the world, but it’s not like it was 20 or 30 years ago, Witt says.

“Managing golf courses is big business,” he says. “It’s sad to say, but anything goes. That’s the evolution of our business. It’s like any other part of corporate America. There are superintendents who will try to get a job someone else already has. There’s no positive attribute about a person who would do that. But the GCSAA can’t suspend or exile them. The right way to look for a job is – whether local, national or international – to set up a good network. Look at the GCSAA employment service. It’s your network of people across the country. You’re aware of when things are going to happen. When it happens, you apply for it.”

A disturbing undercurrent in the industry is typified by Witt’s unidentified friend.

“A friend of mine was trying to get a certain job, and I said, ‘That job isn’t open yet. They haven’t terminated that superintendent. It’s not a job yet.’ And he said, ‘If I don’t go for it, somebody else will.’”

Witt asks if anyone would want to be treated that way.

“If you apply correctly, get your credentials, support material, letters of recommendation, resume, work history, curriculum vitae and photos and send them in, you’ll get a look,” he says. “I understand people can be desperate for jobs. It’s easier to understand why someone might do that, but desperation attempts rarely work.

“You may land a position under somewhat suspect practices, but there’s a good chance that it will take you a long time, if ever, to outgrow what you’ve done with superintendents in the area,” he adds. “There’s a good chance that you would be an outcast because that’s not what most guys are about.” GCI

Explore the March 2008 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- The Cabot Collection announces move into course management

- Carolinas GCSA raises nearly $300,000 for research

- Advanced Turf Solutions’ Scott Lund expands role

- South Carolina’s Tidewater Golf Club completes renovation project

- SePRO to host webinar on plant growth regulators

- Turfco introduces riding applicator

- From the publisher’s pen: The golf guilt trip

- Bob Farren lands Carolinas GCSA highest honor