This fall, turf managers should avoid a potentially problematic occurrence — inefficient fall fertilization.

Low-nitrogen fertility in the fall has emerged due to heavy emphasis on potassium and the fear of creating turf that is too succulent, says Dr. Raymond Snyder, director of agronomy for Harrell’s. “This has resulted in too little nitrogen applied in the fall period,” he says, adding the result is “very poor turf conditions emerging in the spring resulting in the need for growing in of large turf areas and/or sod.”

To better prepare turf for the next season, Snyder advises superintendents to develop more effective fall fertility programs and to utilize a fertilizer product that contains a component of soluble and controlled-release potassium. “Include more rapidly releasing controlled-release nitrogen with a longer lasting controlled-release nitrogen source,” he says.

Superintendents rarely consider photosynthesis, says Aris Gharapetian, director of marketing for Target Specialty Products. “Our plants need sunlight, water and CO2 to make valuable energy,” he says. “This energy will be used to power operations like recovery from summer’s stress, root system regeneration and preparation for winter. With day length, soil moisture and solar energy potential all reduced during the fall, it’s important for turf managers to adjust nutritional plans.”

Secondly, Gharapetian points to nitrogen-driven growth. Nitrogen’s ability to drive shoot growth is less in the fall when compared to springtime applications. “In the spring, we’re cautious to not over apply nitrogen and drive shoot growth at the expense of roots,” he says. “Fall nitrogen reacts in a different manner and affords the opportunity for recovery and carbohydrate production without roots having to pay the price. Moderation is still key.”

Another overlooked issue, Gharapetian says, is potassium’s influence on several plant functions. “Plants use potassium to kick start sugar, protein and starch production,” he says. “This is mission-critical in the fall as these energies are what plants will depend on for winter survival and spring performance. Also, by helping maintain turgor pressure, potassium dramatically lowers a plant’s risk of disease, drought stress and winter injury.

Likewise, zinc plays a small role in more plant reactions than any other nutrient, Gharapetian says. However, its deficiency is rarely noticeable. Zinc helps to keep plants alive in waterlogged soils and zinc regulates plant temperature. This means the plant’s reactions to wild temperature swings are tempered by zinc.

The importance of fall nutrition is often overlooked as nighttime temps are lower, days are shorter and there’s less stress on the plant, Gharapetian says. Turf seems to look better and better as fall proceeds and the tendency is to minimize nutrient inputs. “The fact is, fall is the most critical time of year for proper nutrition,” he says. “This sets the stage for how your turf will overwinter and how it will perform the following season.”

There are a number of reasons for improper fall fertilization, says Dr. James Murphy, extension specialist in turf management for Rutgers University. The amount and complexity of issues a superintendent has to manage compete, and sometimes agronomic issues aren’t at the top of the list. “Experience with different turf and environmental conditions plays a role in one’s understanding of the relative significance of these factors,” he says. “Sometimes, we fall into a rut and do the same thing over and over without taking the time to think critically about the objectives for our actions. But it is important to make the time to review your situation and adjust programs, including fall fertilization, when needed.”

Existing turfgrass conditions dictate whether fall fertilization is needed and, if so, how much, Murphy says. “An older turf that is healthy and vigorous requires much less fertilization than a young immature turf,” he says. “Therefore, the longer you manage a turf, it is more likely that you will need to adjust fertilization rates down to avoid over-fertilizing.”

A sparse, worn-out turf needs more fertilization to help with recovery than a healthy, dense stand of grass, Murphy says. Additionally, the immediate need for recovery in a worn-out turf dictates that more (and perhaps all) of the nitrogen should be in the quick-release form rather than the slow-release form.

“Fall fertilization, especially with nitrogen and phosphate, favors the development of annual bluegrass over other cool-seasons turfgrasses, including creeping bentgrass, Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue,” he says. “As a result, superintendents who want to discourage annual bluegrass encroachment should consider withholding or at least minimizing fall fertilization.”

The timing of fertilization, as well as the nitrogen source(s), control whether fall fertilization results in turf responses primarily during the fall or spring. For example, early fall applications containing greater percentages of quick-release nitrogen (ammoniacal, nitrate, urea forms) result in the turf responding during fall. Conversely, applications later in the fall or containing a greater percentage of slow-release (water insoluble and coated forms) nitrogen will shift the turf responses toward early spring.

“It is important to determine which responses are needed (fall or spring) and pick a timing and fertilizer product that provides that,” Murphy says. “Turf that needs to grow actively in both fall and spring (for example, annual bluegrass turf) would benefit from both an early fall fertilization with quick-release nitrogen and a late-fall fertilization that includes a larger percentage of slow-release nitrogen.”

Fall fertilization needs to start sooner in more northern (colder) regions. “Late fall fertilization in New Jersey typically occurs during November,” Murphy says. “However, November is often too late for a colder region such as northern New England, especially if a turf response is expected this fall.”

Nitrogen and phosphate fertilizers should not be applied when the soil’s water content is high (wet) or frozen. Both conditions encourage nutrient loss from runoff or leaching. Similarly, nitrogen and phosphate fertilizers should not be applied to dormant turf.

Adequate potassium access for the entire season is too often overlooked in all types of turf, says Dr. Larry Murphy, owner of Murphy Agro.

“Winter hardiness is tremendously important for cool-season species and should not be overlooked for warm-season species, particularly if there is a chance of occasional freezing,” he says. “Many turf grades or mixes simply do not supply sufficient potassium. Loss of stand can frequently be attributed to low available potassium from all sources, soil and fertilizer. Sufficient potassium is critical for sugar synthesis and transport and for retention of water.”

Other nutrients are crucial for fall and winter vigor and hardiness. For example, Larry Murphy says phosphorus is very important at all times but poses a “dilemma” where restrictions have been placed on its use in fertilization.

“Run-off and erosion are the mechanisms of loss, but phosphorus reactions with soil components (fixation) are the big reasons for poor utilization efficiency,” he says. Phosphorus availability and uptake should be enhanced if possible by treatment of either dry or liquid phosphorus with a polymer having a high concentration of carboxyl groups that “diminish soil phosphorus fixation reactions.”

Joel Simmons, president of EarthWorks, believes biological soil management (BSM), an approach he’s advocated for three decades for all soil types. BSM uses carbon-based fertility, which helps provide long-term feeding opportunities for the soil’s microbial populations. Carbon-based fertilizers balance the carbon/nitrogen ratio in the soil and can be blended with or without synthetic fertilizer.

“If I had only had one fertilizer application to make all year it would be a winter or dormant feed application with a carbon-based product,” Simmons says.

As the turf’s top growth slows down in mid to late fall in many parts of the country, microbial activity under the turf layer is still very active and a good feeding of the microbial activity can help to break down thatch, flocculate the soil, build water holding capacities, buffer sodium build up, and help to bring a quick and vibrant spring green up, Simmons says.

“If this same application is made without a carbon base, the available carbon in the soil that is used by microbes for all these vital functions is burned up and the soil and the plant can suffer,” he says.

By balancing the carbon to nitrogen ratio in the soil, Simmons says nitrogen “rolls through” nitrification more efficiently, allowing superintendents to use less fertility with better recovery because microbes are more active, and more fertility is being made available to the plant. “Even in 12-month environments the winter feed can be of great value for the same biological reasons as in cooler parts of the country,” Simmons adds. “The only weather conditions to avoid may be applying to frozen soils because of the potential for surface run off.”

The message is clear: Do not overlook or undervalue any basic when it comes to feeding your turf this fall. Your reward will be a healthy stand and a beautiful green up come spring.

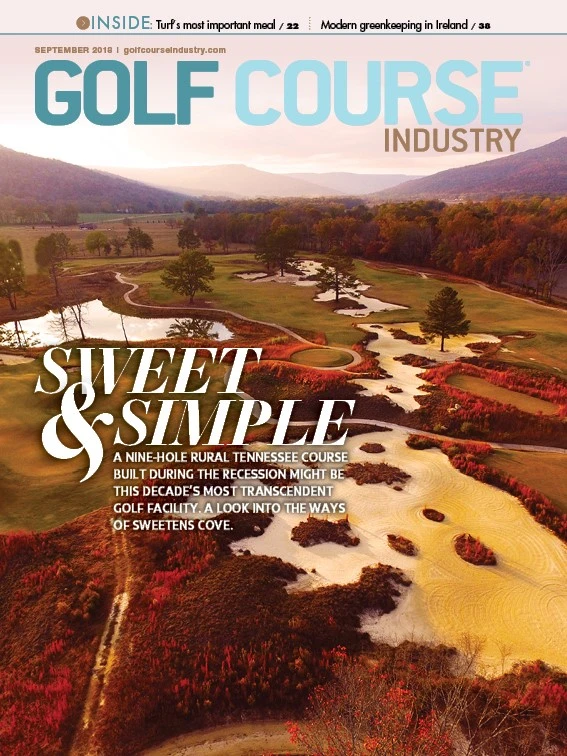

Explore the September 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- LOKSAND opens North American office

- Standard Golf announces new product lineup for 2025

- The Salt Pond taps Troon for management

- KemperSports selected to manage Swansea Country Club

- From the publisher’s pen: Grab that guide

- Introducing our April 2025 issue

- South Carolina leaders honor golf course superintendent

- One and only