When Jimmy Alston, superintendent at Eagle Creek Golf Club in Naples, Fla., finished planting the last new sprigs in the middle of August, he breathed a sigh of relief.

He and his team had pulled together and made hard choices, but they hit the last possible deadline on their renovation. They would open Oct. 15 to greet the season with a beautiful, challenging course.

A few weeks later, Hurricane Irma struck.

A private 18-hole Larry Packard-designed course that opened in 1985, Eagle Creek was known for compact design surrounded by the wilds, with true par 5s almost literally carved out of the jungle.

“If you miss the roughs to the right by, say, three feet, because we’re so heavily tree-lined, 90 percent of the time, you’re chipping out of there sideways,” Alston says. “When I say ‘jungle,’ there are areas where if you hit a ball in there, you just didn’t walk in after it.”

The course is packed into 300 acres of cypress pine and palm trees and serves as a meeting point of fresh and saltwater in the area. In that space are 200 homes, with about 50 percent condos and 50 percent single-family houses. The course has 355 current golf members, with a soft cap of 360, and bylaws set a firm stopping point of 380.

That meant short waits for tee times for those members, sometimes just two days in advance. Walking the course, members could expect Stimpmeter readings between 11-12, which is how they preferred it.

“It’s rare that we’re outside that range,” Alston says. “We spend more time monitoring and working on greens than anywhere else by far, and our members feel the same way. Everything’s about greens.”

And Alston had worked hard to restore those greens after joining the staff about 10 years ago. He described the cut he pulled out when he started as “fudge,” he says. But years of hard work brought the greens to life in the jungle, to a point that Ken Venturi eventually described them with the term “PGA Tour-ready,” Alston says.

Even if Hurricane Irma had hit at another time or during the past few years, it had a solid chance of striking during renovation. After recovering Eagle Creek, Alston and the greens committee established a plan of slow, small improvements rather than large-scale renovations.

“Down here, when it’s time to renovate, all the folks down here … literally scrape the course up and put it in a pile off to the side, then they build it brand-spanking new,” Alston says. “I’ve never understood that, and it didn’t make sense to the Eagle Creek members or the greens committee.”

So, five years ago, they developed a 35-year master renovation plan, with different-size projects every year to keep up with current equipment and changes to the game. The projects weren’t as much “Rebuild No. 1,” as much as “Rebuild the back tee and move it 10 yards to the left,” Alston says.

“Those are the kinds of things you’ll see in our master plan,” he adds. “Eagle Creek members love their golf course. Why blow it up and change it?” In the last five years, they’ve put about $2 million total into the course for steady renovations.

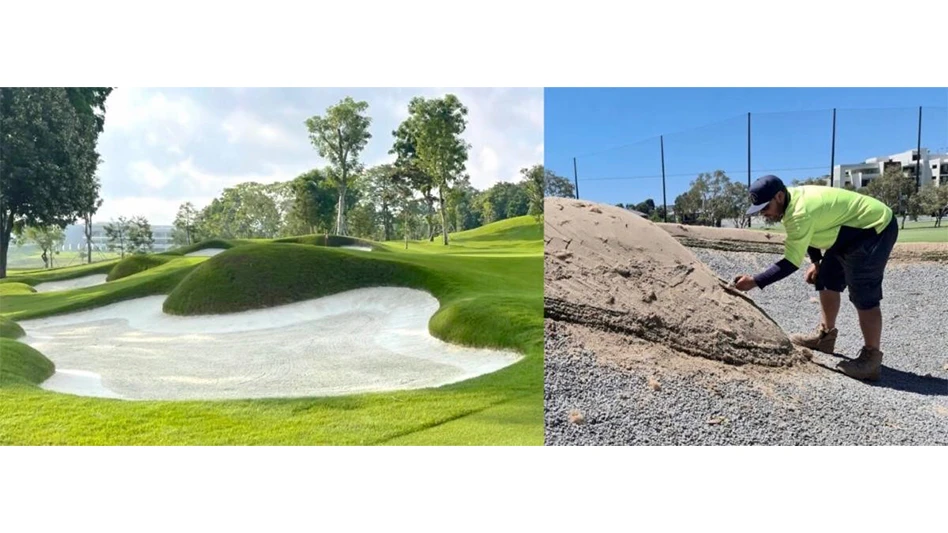

So, a few years ago, they did projects like putting in bulkhead seawalls on the edge of the lake, and widening the approach right in front of the green on No. 4. But the project on the books for 2017 was one of the largest in the plan so far: Renovating five finishing holes.

“Instead of saying, ‘Let’s put a quarter-million into rebuilding No. 2,’ we said, ‘Let’s put $100,000 in each of our last five finishing holes, and make those good holes even better,’” Alston says.

The project took two years of planning, in customary small steps: regrassing the roughs with Celebration Bermudagrass, renovating the tees and fairways the previous year, adding drainage projects and enhancements.

Olsten worked with architect Gordy Lewis beginning on projects about seven years ago, and the partnership had only matured over the past few years. Lewis ended up on Eagle Creek’s greens committees, which made Olsten’s requests much easier, he says.

“They’re really able to get into one-on-one with a golf course architect about changes. I just sit back and they duke it out, and I get my work orders,” Alston says. “It ensures that once we go out on the course and spend our members’ money and we make a change, we know they’re going to love it.”

Eagle Creek closed May 15 to begin construction, but the summer had other plans. Even before the hurricane, the course received multiple record rainfall events, with at least two in June and then July dumping more than nine inches of rain in 24 hours.

“Couple that with being three feet above sea level, and you’ve got a swamp,” Alston says. “It was unreal.”

One month behind schedule in delays, Alston and his team finally had the end in sight, a drop-dead final day to have sprigging finished in time to open: Aug. 15.

“It was like, ‘Yes, we’re gonna make it,’” he says.

Everything came together, even with some field plan changes to make up for the troublesome weather. With Lewis on-site, they had much more room to work when things didn’t quite line up, and Golf Course Irrigation and Drainage Inc.’s site project manager kept the renovation moving whenever they were able.

“Having a flexible architect in Gordy, having an incredibly talented golf course construction manager and our relationship with the greens committee, we were able to make those changes in the field for the better 99 percent of the time,” Alston says.

Two weeks later, evacuations were underway for Miami, and Eagle Creek’s hurricane and disaster plan was already in effect. Communication was key, and frequent messages went out to members via social media and YouTube about weather predictions and how the team was preparing.

“We’ve got a pretty extensive hurricane and disaster plan,” Alston says. “We’ve had many [storms] and we’re always going to have them, so having a good plan saves money, saves time, saves work. It gets everybody safe, that’s the first thing.”

Seven days out from landfall, the team watched the news and tracked reports. Eagle Creek had bounced back from a direct hit by Hurricane Wilma in 2005, and they were ready to weather another. “Hurricanes are hurricanes. You work, and you clean it all up and get things back to normal,” Alston says.

Then, as distance closed, a prediction for a 15- to 20-foot storm surge came through, and everything in the preparation plan changed.

“If we had gotten a 10-foot storm surge, Eagle Creek would’ve been completely wiped off the map,” Alston says. “It would’ve been in the Gulf of Mexico. Homes would’ve been submerged. Everything would’ve been 100 percent destroyed.”

Many people from Eagle Creek evacuated, especially those with families, says Alston. But Alston, his assistant and the general manager and a few others stayed nearby to ride out the storm. The hurricane changed track at the last moment, barreling down on Naples.

Alston sheltered about 15 miles north of the course and logged into the course’s security cameras remotely to watch what he could. Eagle Creek ended up with the dubious honor of being the first 18-hole golf course and country club hit by Hurricane Irma on U.S. soil.

“I remember, being online, I was hunkered down watching the cameras,” he says. “And you see the trees start to lean, and then bang, the power goes out. Right then, the internet went out. Then cell service went out. Then cable TV went out.”

“For a good 24 hours, we didn’t know what had happened at Eagle Creek. We didn’t know if it had gotten the storm surge. We were completely cut off. Even after the storm and winds had died down, Sunday night, you couldn’t get on the roads and drive down.”

Along with the chainsaws that he and his assistant brought in their attempt to reach the course on Sunday night, Alston also brought a boat, just for the worst-case scenario. In his gut, he thought the course might just be gone, thanks to the storm surge. In the morning, he wondered if he and the others still had jobs at all.

“We were thinking, number one, how do we get [to the course] from where we are, and two, do we have members who are dead?” he says.

The first thing he did was pull into the entrance at Eagle Creek and took a picture with his cell phone. Miraculously, he had cell service, and tweeted out the image to members and followers to let them know that at least that part of the course was still standing.

“Honest to god, it was like, arms up, laughing, it’s still here!” he says.

Then he went down to the shop to start taking out chainsaws and bulldozers and get to the work of surveying the damage.

The first order of business was to take a wheel loader and clear the streets as quickly as possible, to help members who had stayed behind and who were blocked in by a street full of fallen palm trees and debris.

“Those streets were all 100 percent blocked. You couldn’t drive out with a four-wheel-drive pickup,” Alston says. “We wanted to get as much infrastructure going as quick as possible. We basically snowplowed all the streets, but it was palm fronds, and trees and limbs and bushes instead of snow, thank god.”

The first week took their communication methods back to the Stone Age, as cell service was spotty at best and the team was spread across the country to various evacuation points, like Michigan or Pennsylvania. It took multiple phone calls and networking to make sure payroll happened on time and employees knew when and where to show up.

During the cleanup effort, Alston and his staff continued to take video or photos of updates, and through the team’s network, they sent out push notifications to keep members updated.

Though Eagle Creek didn’t end up getting the storm surge they had been warned about, but what they did get was 23 inches of rain in about a four-hour period and Category 4-force winds, says Alston.

“The course was flooded, it was just incredibly flooded,” he adds. “You could see more debris than you could grass. It was hard to tell it was a golf course for, I would say, about a week.”

Despite the damage, Alston and his greens committee wanted to get the course open as quickly as possible. The course was originally scheduled to open Oct. 15, and they set a goal to open by Nov. 15. “Then we started on hole No. 1 and basically put together a four-phase cleanup plan,” he says.

Phase 1 was just getting small debris off the turf so they could get back to the business of managing the turf itself. Alston kept a close eye especially on the 12 acres of brand-new sprigs that were trying to grow in without the help of an irrigation system.

“We just piled stuff up on the edges of the cart path, on the edges of the woodlines so we could at least start mowing turf,” he says. “There were literally holes of the course where they weren’t mowed for almost a month.”

Clearing away the small debris took about 21 work days, while the team still waited on reliable electricity and water sources.

Phase 2 started work on the fallen trees and uprooted stumps. Given how heavily wooded Eagle Creek had been, they had more to lose to start. Alston’s initial count a week out from the storm was that they had about 1,500 trees down, and it was another 34 work days spent there. Even with the heavy amount of work ahead, Alston relied on his team, but also on a helpful coincidence: GCID had still been doing some minor work on the course when the storm hit. They were still under contract and were more than willing to make the shift from doing golf course construction to hurricane cleanup.

Phase 3 was hand-raking the debris from peripheral landscape areas, where no machine would be able to help clean, and Phase 4 meant starting the replacement of lost trees, and the removal of the dead and dying trees still standing.

On top of the 1,500 trees lost to the storm, Eagle Creek is still losing trees to the southern pine beetle at the rate of about seven trees per day, says Alston. He estimates that they’ve lost about another 350 trees so far, and the beetle’s attack could go on for another six months or a year.

With the cleanup plan underway and moving, Eagle Creek opened for the season Nov. 15, “with a lot of ground in repair, everywhere,” says Alston.

Hole No. 9 was cart path only, for example. Alston and his team were working in the peripherals while golfers were playing around them. But it was playable.

“That was our goal all along: Get it playable,” Alston says. “We worked basically from the centerline of each hole outwards. We’re happy to have a season, at this point.”

Though insurance claims have been filed, Alston has been approaching the cleanup as frugally as possible in the interim, and all capital improvement projects have been put on hold. Given Eagle Creek’s system of smaller, systematic improvements, that meant between $800,000 and $1 million was available to work with to keep the effort moving. Even with the hard work of his team and others, the recovery will take almost all of 2018, he says.

As the course has bounced back, Eagle Creek’s players have been understanding, says Alston. Most of them have seen storms come through before, and they’ve all had damage done to their homes by Hurricane Irma.

“What I’ve heard the most is, ‘I can’t believe how good it looks,’” says Alston. “And it does, it’s got a really long way to go, but considering what we had, it looks pretty darn good.”

Explore the March 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Toro continues support of National Mayor’s Challenge for Water Conservation

- A different kind of long distance

- Golf Construction Conversations: Stephen Hope

- EnP welcomes new sales manager

- DLF opening centers in Oregon, Ontario

- Buffalo Turbine unveils battery-powered debris blower

- Beyond the Page 66: Keep looking up

- SePRO hires new technical specialist