Contrasting in form, feel, lay and land, the Donald Ross and Pete Dye Courses at historic French Lick Resort make for a unique pair of playing partners. The unlikely bedfellows represent French Lick as the only locale in the world boasting designs by the two generational legends.

“And the only resort or property with two World Golf Hall of Fame architects,” French Lick Resort director of golf Dave Harner says. “The best of the classic era, and the best of the modern era. Sure, there will always be debates about the best designer now, but if you look at Pete’s record and his courses and the rankings – then a strong case can be made for Pete.”

Opened in 1917 amid the popularity of the burgeoning Midwest resort destination as “The Hill Course,” the Ross design would host the PGA Championship just seven years later, won by Walter Hagen.

Nearly a century removed from its opening, as part of a $600 million renovation of the resort, the Hill enjoyed an eponymous rename, along with a thorough restoration by Lee Schmidt (with assistance from the Donald Ross Society) to bring the classic track back to its original design intentions. Today, the course annually tests the women’s up-and-comers as the home of the Symetra Tour’s Donald Ross Classic each July.

The Pete Dye Course, boldly situated on Mt. Airie (reputed as the second-highest point in the state) debuted in 2009 as the 21st of 22 course designs in the architect’s adopted home state. Considered by many an instant classic for its grand vision and verdant setting, the course hosted the Senior PGA Championship in 2015, and is the annual home to the Senior LPGA Championship.

A Tale of Two Plays

While akin in stature and ranking recognition, the Dye and Ross share little else in common.

Like many if not most of the approximately 400 domestic designs or redesigns bearing his name, the Ross has stood the test of playable time. Aided by the $5 million restoration in 2005, the Golden Age course finds its name defense, definition and demand in highly strategic green complexes. At French Lick, the test is furthered by deep-faced bunkering and naturally undulating fairways resulting in a flow of hilly lies.

On the Dye, the designer’s penal penchant is amply in play across 330 acres of course, which sees the card tipping-out at (gulp) 8,102 yards (not that many spike marks are found back there). Appropriate driving lines from boxes are continually critical for placement (hence the required forecaddie), lest the player seeks swings of the acrobatic variety from playable, albeit dramatically slanted rough or amid the “volcano” style bunkering. The contrasting styles of era are augmented by different grasses, a dichotomy that sees a name difference in putting the biscuit in the basket.

“Pete’s greens aren’t as severe as over the Ross, but they’re a lot faster, and that’s by necessity,” Harner says. “Some of the Ross greens have seven or eight feet of fall from tier-to-tier, back-to-front or side-to-side. If you put those things running at a 12? You could drop the ball, and it’ll roll off the putting surface. And, being an old golf course, you’re going to have the Poa in the greens, and you’ll always have some. That’s always a challenge early in the spring and, yeah, it can get a bit bumpy in the afternoons, but we work to combat that with a growth retardant to try and knock back the seed heads.”

The creation of the Dye – resulting in three million cubic yards of movement, according to Harner – is itself the stuff of design legend.

“Pete and I walked the property early on, and the first thing he told me was that we couldn’t build a course here – it was too severe,” Harner says. “Then he came back – he had gotten ahold of an old topo map from the 1940s – and he played a connect-the-dots. He picked the 36 highest points and connected all the tees and greens.

“We walked it again along those spots and saw all the unrestricted views,” he adds. “And then we went to a local restaurant, he drew the thing on a cocktail napkin and said, ‘Here’s your golf course.’ And that napkin is all we got. You can see it in the pro shop.”

Caring for Eras

Though the two courses play under the umbrella of French Lick Resort, the work of the course superintendents may as well be as far apart as the respective course debuts.

“Pete moved the earth to build that golf course, and here, they worked around the land," says Brett Fleck, golf course superintendent at The Donald Ross Course, which sports a spread of 135 acres, about 75 of which are maintained.

Coloring the image further, Harner says: “When Ross was hired to design the course, he and the owner jumped on horses and rode through the country until Ross found a piece of ground that he wanted to build a golf course on.”

Save for the exterior routing of native grasses, the two courses see little comparison in daily aesthetics, though the peripheral heather is itself a contrast of different playing philosophies.

“If you hit a ball in the native grasses here, don’t waste your time walking in there.” Fleck says. “But at the Dye, their goal is to enable the player to have more room, find that ball off the fairway and try to play it.”

From one super to another, the Dye and Ross are no twin sisters.

“It’s hard to compare the two,” Fleck adds. “I mean, the Dye fairways are sand-based, so they’re doing stuff like using wetting agents, which I don’t have to do. I’ve got the heavy soils, and we’re trying to get the water to move through ’em, and they’re trying to get water to hold.”

Grass varieties further denote key differences.

“Here, we’re completely different grass types, with Bluegrass Bermuda fairways, while they’ve got bent,” Fleck says. "Their greens are sand-based, push-up USGA greens; we’re still dealing with 100-plus-year-old greens and native soils. Being open over a century, we’ve got all kinds of different grasses growing; just in the rough, we’ve got Poa, Bermuda, fescue, rye – you name it, the variety is in there.”

Furthering Dye’s local influence, homespun flavor on his namesake is found via the superintendent Russ Apple, a native of the area who worked at the Ross during high school before his turf degree at Purdue University led to his big break. Reputedly hand-picked by Dye to get the gig, Apple shakes his head when reflecting back on his hire in ’07.

“Basically, the first six holes were seeded, but everything else was still dirt. So, it was chaos,” Apple laughs. “When Dave (Harner) brought me up here, he said, ‘Seven days a week, daylight to dark, no more money. Take it or leave it right now.’ You don’t walk up here, get told that and think it’s gonna be easy work. You need to plan for a long road – but it’s been a good road.”

The massive task of working the dramatic setting is peppered with provincial pride, as the vast wealth of Apple’s hires in subsequent years have seen the superintendent bring on numerous area employees, most of whom were new to the industry. Said ideology is enhanced by a philosophy of humility.

“I like to keep things as simple as you can agronomically, but get the best conditions as possible,” Apple adds. “You can’t charge what we do and have bad turf, well, anywhere.”

Well-versed that golfers of all levels are wont to miss fairways, a Turf-type tall fescue proves a key course condition.

“If we mowed it any tighter, it can thin-up and get diseases,” Apple says of rough that has a helpful habit of propping up balls askew of fairways. “And it’s got to be cut as fair as possible, because many of the stances in the rough will find a baseball swing.”

The theater of elevations off-fairways is not a task for the timid.

“You can’t just take any person on a machine out there and mow,” Apple continues. “I’ve been around enough to know that there are challenges we deal with on a daily basis that a lotta people don’t.”

Such challenges found an earnest task with landslide concerns in 2012.

“We came out of winter and what was then our ninth hole – now our 18th — and we saw, like, a fracture on the green,” Apple says. “The irrigation was starting to pull apart and, over two years, the right half of the green just kept slowly sinking. By the time we made the decision to change the green, the one side was over three feet lower.”

Dye came back in to redesign the key change with little time to spare. “We lowered the green by about 12 feet,” Apple says, “and did it in the winter because we had the Big Ten Championship coming back in April.”

Separate but equal in generational caliber, the two courses – and the men who man them – each beat with a heartland soul across their respective soils.

Not that the two superintendents have any intent in trading places.

“These courses are two totally different animals,” says Fleck with an easy grin. “But I’m used to this animal. I wouldn't want his job, and I don’t think he’d want mine.”

Explore the September 2019 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Technology diffusion and turf

- Applications open for 2025 Syngenta Business Institute

- Smart Greens Episode 1: Welcome to the digital agronomy era

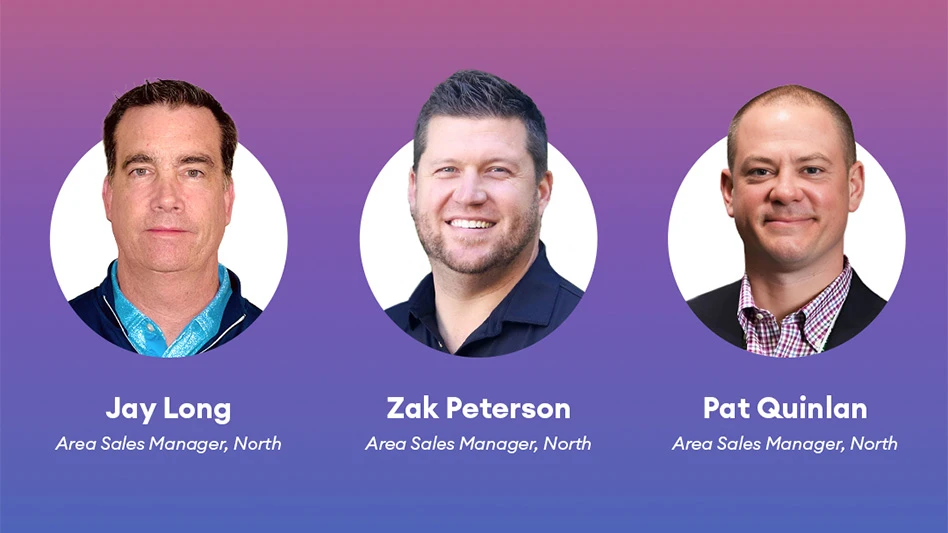

- PBI-Gordon promotes Jeff Marvin

- USGA investing $1 million into Western Pennsylvania public golf

- KemperSports taps new strategy EVP

- Audubon International marks Earth Day in growth mode

- Editor’s notebook: Do your part