On New Year’s Day 2018, we lost two veteran golf course architects – Jeff Hardin and Dick Nugent. Dick was my first (and only, along with his partner Ken Killian) golf course architecture boss and mentor.

I learned most of what I know about the theory and business of golf course architecture from Dick. I am still influenced by his design style. In 1993, I told Golf Course News, “I find my work going right back to what Nugent told me, that Robert Bruce Harris told him in 1959.” My proteges probably are telling their staff what I told them in the 1990s, that Nugent told me in 1977, that Robert Bruce Harris told him in 1949.” His legacy is extending the theories and methods of the “Chicago School” of Architecture.

That legacy includes design variety and consistent design quality. After splitting with Ken Killian, he experimented extensively, styling courses in homage to Pine Valley, Dunes Club in Michigan, Scotland, the Golf Club of Illinois, and modern design (with whimsey, at Harborside International in Chicago). While most often designing reasonable cost municipal courses, he also designed one of the world’s toughest courses, Koolau in Hawaii.

It equally entails treating everyone with respect and generosity, and acting as aa mentor to the many who worked for him. Most of use view him as a father figure, who influenced us professionally as much as our own fathers influenced us personally. He was a great mentor to many aspiring golf course architects, and many who went on to success on their own.

While I started with Killian and Nugent upon graduating college in 1977, our relationship started when I was 12. I went home from my first golf round wanting to be a golf course architect. My father searched for information about golf course architecture as he could – no small feat pre-Google – and found, among other things, that there was a golf course architecture firm, one stop down the train tracks. I wrote them, and Dick invited me for an office visit, where he encouraged and guided me to study drafting in high school, landscape architecture in college, including surveying, agronomy, construction management, ecology, business practice, aerial photography interpretation, all supplemented with summer jobs on golf courses or landscape construction.

I followed his advice and they probably felt obligated to hire me to an entry-level position, despite a sluggish economy. I wondered if golf architecture would be a profession when I was his age. He scoffed, “Golf has been going strong for 500 years, it will last the next 50!” That was the first of many memorable stories and sound bites. I still recall (and quote) his design rule to “Avoid sharp doglegs in only two situations … where there are trees, and where there aren’t.”

My education only accelerated once there. Dick made all young associates work in construction for several months, to enhance their design knowledge.

He allowed young associates to be involved in design, if we adhered to his basic style, which was big and bold. Dick believed subtlety was “lost” on modern players. He inspired our creativity by exhorting that “no architect ever got famous by being timid.” He encouraged numerous wild design ideas, figuring one in a hundred would be good.

My first design experience was a par-3 hole, where I sketched in a forced water carry. He walked off in silence, and I thought I might not see a fourth day. He came back later, explaining that they “tried a forced carry once, and the ladies couldn’t play it, so he avoided them ever since.” He also changed my convex green surface (great for drainage!) to a concave one, gently explaining that “average golfers need all the help we can give them ... ”

Through experience, Dick had developed many design rules. He loved to break those rules occasionally to enhance design, but cautioned that breaking established rules too often quickly turned a course from playable to unplayable and unbearable. Worried about being typecast, he strove to utilize a few completely new design ideas on every project to avoid becoming stale.

His roots included high doses of engineering and he believed that “cost/value engineered plans” were part of an architect’s duty to the owner. We drew extensive grading, irrigation and drainage plans. Most firms claim to produce the “best plans in the business,” but Dick’s claims were legitimate. He left little to chance in the field. Say what you want about his design style, Dick Nugent courses drained!

To him, detailed grading plans were golf course design, and he thought architects should be able to draw what they imagined. We were often instructed to survey good design features, so we could draw them more accurately. Our grading plans also calculated cut and fill. Our grading was efficiently balanced for the entire job, but also on individual holes to reduce the contractor’s haul lengths and save the owner money.

Cut and fill imbalances can be easily corrected by lowering or raising entire areas. However, when our “first run” showed imbalances, Dick reviewed the plans to eliminate unnecessary cuts or fills to balance and reduce earthmoving quantities, a process that often entailed a second and even third try. When an associate left for another firm, he reported back that our earthwork methods “were a revelation” to his new bosses.

Dick saw the value in small projects. When I complained about designing a low budget project, he said I was doing “more for golf” by designing a good, affordable course in rural Wisconsin than by building an expensive country club in Chicago.” That project was Lake Arrowhead in Nekoosa, Wis., and it’s proven popular for 38 years, and at reasonable prices. Sand Valley is now next door, and doing well, but I think Dick was probably right.

Personally, he was affable and generous. His primary team building method was the office lunch. Dick paid for lunch, and for trips to famous courses to expand our design horizons. He paid for our memberships in ASGCA, knowing we would probably leave the firm upon attaining full membership. And we did.

Over the years, I have nothing but fond memories of working Dick. I still use the methods he taught me in my own work. If the sign of a great mentor is long lasting effect, no one should doubt that Dick Nugent was one of the great mentors in a game filled with great mentors.

Explore the February 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

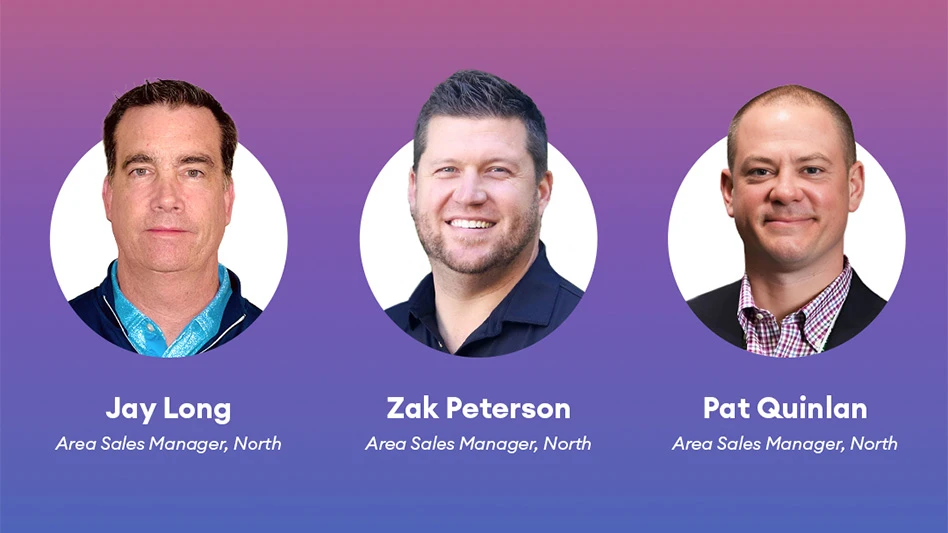

- PBI-Gordon promotes Jeff Marvin

- USGA investing $1 million into Western Pennsylvania public golf

- KemperSports taps new strategy EVP

- Audubon International marks Earth Day in growth mode

- Editor’s notebook: Do your part

- Greens with Envy 66: A Southern spring road trip

- GCSAA’s Rounds 4 Research auction begins

- Quali-Pro hires new technical services manager