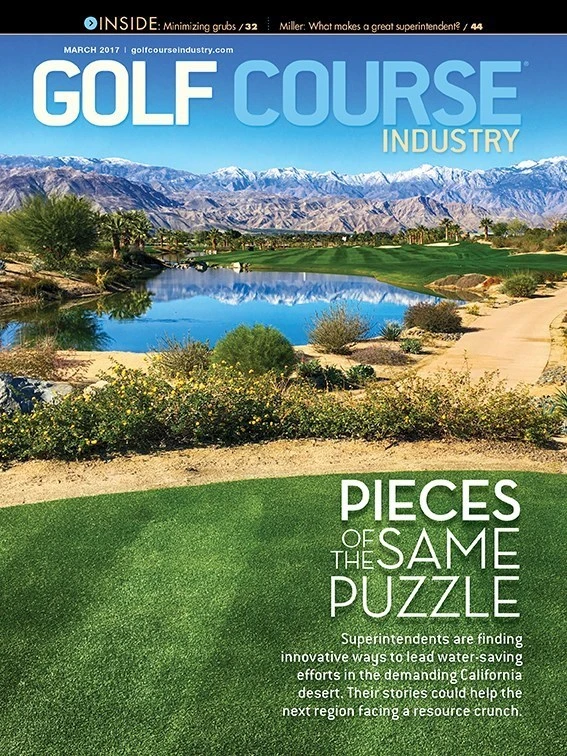

Behind gates and walls, snugged between houses, and below mountains and omnipresent sun, rests one of the golf industry’s biggest conundrums. A desert supports a vibrant and viable golf tapestry.

Tyler Tang spends a late-January afternoon zooming around The Club at Morningside in Rancho Mirage, Calif., explaining how he maintains a 140-acre golf course in a desert. Temperatures are in the low-70s as sun reflects off the bordering San Jacinto Mountains. Snowbirds three weeks into their transient winter existences pack a course opened in the early 1980s.

Weather is the top attraction in Rancho Mirage, one of nine cities comprising Southern California’s Coachella Valley. With the weather, comes golf. Plenty of it. A 50-square mile stretch boasts 123 golf courses. Thousands of homes surround the courses and developers use phrases such as “deep emerald turf against ever-changing desert colors,” “lush landscape palette” and “immaculately maintained” as marketing tools on club websites.

Back-porch aesthetics and decades-old promises place superintendents in tricky spots. Do too much to adapt a course to the surrounding environment and customers could purchase homes and memberships elsewhere. Yet changing little, or nothing, could place a facility in a tenuous spot. “By the time, you realize you should have been with the program, you’re five to seven years out of date,” says Craig Kessler, the Southern California Golf Association’s director of government affairs and chair of the Coachella Valley Golf & Water Task Force.

Kessler made his comments at the second annual Coachella Valley Golf Industry Summit in late January. He warns state leaders are ready to pounce on the region whenever the next widespread drought intensifies. The Coachella Valley averages less than six inches of rain per year, so it can be argued the region never leaves drought.

A day after the summit, Tang drives his cart toward the corner of Country Club Drive and Highway 111, a sloping expanse offering outsiders a peek into The Club at Morningside. The entire 14th hole is visible from the intersection. The tee, fairway and green are a verdant green. The rough is a mix of green and brown. The club opted last fall against overseeding 35 acres that borders the 13th and 14th fairways and covers landing areas of the driving range.

“Everybody was on board with it,” says Tang, the club’s superintendence since 2015. “With what was in the media and newspapers, then (members) coming back and seeing how proactive we had been, they totally accepted it which is great. It’s out of play, it’s not backed up to anybody’s home or lawn. That does help with the initial blow of having brown grass.”

From discolored turf in wayward areas to replacing turf with desertscape along cart paths, tees and medians, superintendents are tactfully pursuing water-saving projects and practices once deemed risky in a competitive market. Methodical shifts are occurring despite favorable water prices and lenient conservation mandates, at least by California standards.

GCI spent two days earlier this winter observing Coachella Valley golf course maintenance and business practices. Lessons shared by proactive desert facilities can be applied wherever golf courses face scrutiny over water usage.

Start now

Stu Rowland, the director of golf course operations at Rancho La Quinta Country Club, relishes conversations about golf’s water usage. But when he arrived in the Coachella Valley in 2002, he fielded few questions about the subject. An expansive aquifer, longstanding access to Colorado River water through the All-American canal and water districts that understand how golf aesthetics attract residents shielded the Coachella Valley from issues facing other sunshine markets such as Los Angeles, San Diego, Las Vegas, Phoenix and Tucson.

“Nobody really talked about water,” Rowland says. “Water was terribly cheap – really, really cheap. Unless you are getting it for free or pumping out of a river like some other parts of the country, it was the next cheapest you could get.”

A drought that started in 2012 and recently ended in most of California placed the region in the conservation spotlight. Media outlets started tossing haymakers at the Coachella Valley golf industry, using terms such as “sucking California dry,” “slow to conserve” and “water guzzling” in headlines. Fair or not, superintendents hired to produce looks impossible to achieve without abundant water found themselves in an emotional debate extending beyond club walls. “We have this huge target, which I think is interesting because I have never met a superintendent that’s excited about depleting a resource that helps him keep his job,” Rowland says.

Rowland has worked with members and homeowners to conserve water without damaging the intent of the 393 acres and 36 holes his crew of 62 employees maintains. Rancho La Quinta pursued a water-driven project last summer when the crew replaced 3 ½ acres of maintained turf surrounding the 18th hole of the club’s Jerry Pate-designed course with a variety of desert plants. The area is being watered using drip instead of overhead irrigation.

It’s too soon to quantify the savings, but Rowland says installing drip irrigation and drought-tolerant plants in 32 acres of landscape areas contributed to the club saving 200 acre-feet of water in 2016. One acre-foot is equivalent to 325,851 gallons. Similar projects are being considered. When altering aesthetics because of water concerns, Rowland says it’s important to provide clarity about the reasons behind the change and how it will impact the member and homeowner experience.

“Start now on what your contingency plan is,” he says. “Have that communicated so that if there’s a drought or water shortage everybody is on board with the plan and what the plan entails. When worst comes to worst, tell them this is what we are going to water and this is what we are not going to water and this is what it’s going to look like so there’s not that shock factor and knee-jerk reaction.”

Focus on playing areas

Reliability is a staple of Coachella Valley golf. Members and homeowners arrive each winter expecting to see the same people and views they enjoyed the previous year.

Opened in 1959, Bermuda Dunes Country Club produced more than five decades of repeatable experiences. Bermuda Dunes served as one of the sites for the PGA Tour’s desert tournament from 1960-2009. A group consisting of Gerald Ford, George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton and defending tournament champ Scott Hoch joined tournament host Bob Hope for a pro-am round on the course in 1995.

Superintendent Chris Hoyer will likely never prepare Bermuda Dunes for three presidents, a cranky PGA Tour player and beloved entertainer. But he did usher the club through one of the biggest transformations in its venerable history.

Bermuda Dunes, a 27-hole facility with 185 maintained acres, halted wall-to-wall overseeding in 2015. With help from golf course architect Tim Jackson of Jackson Kahn Design, the club identified a water-saving model that would require one height of cut for all fairway, tee and approach turf. Eighty acres of playing areas are overseeded while the other 105 acres turn dormant. Uniform tees, fairways and approaches promote course setup flexibility and shotmaking versatility.

Hoyer, who arrived in 2015, used long-term thinking when explaining the changes to members. He knew the dormant Bermudagrass would initially struggle because of the toll decades of overseeding below trees exerted on turf. Seeding problem areas didn’t work, so sod was needed to cover dirt patches.

“What was communicated – and it was overcommunicated over and over – was that we are going to strive to make sure the turf that we do overseed in the playability areas is the best (members) have seen because we knew the rough and other areas were going to struggle,” Hoyer says. “Having that plan in place and presenting it to the membership was really beneficial for us as a management team to portray it, and say, ‘This is how it’s going to work.’ We didn’t want to overpromise and underdeliver.”

Full Bermudagrass coverage in dormant areas has increased this winter to 90 percent, according to Hoyer. The changes position Bermuda Dunes to handle future conservation targets while saving the club more than $200,000 per year because of reduced water, seed, pesticide, labor, fertilizer and energy costs. Hoyer and his crew also replaced 2½ acres of maintained turf between the ninth green and a road leading to the clubhouse with desertscape as part of a Coachella Valley Water District rebate program offering courses $15,000 per acre for up to seven acres of removed turf.

“We wanted to get ahead of the 8-ball,” Hoyer says. “We didn’t want to be left behind saying, ‘What are we doing to conserve water and meet our goal that we had set as an industry?’”

A different era

Across Country Club Drive from The Club at Morningside, sits Thunderbird Country Club, the Coachella Valley’s first 18-hole course and a symbolic cog in regional golf discussions.

Lawrence Hughes, who worked as a construction supervisor under Donald Ross, cracked the opening tee shot on the Coachella Valley’s first 18-hole course on Jan. 9, 1951. The club then blossomed as it hosted the 1955 Ryder Cup, inspired a name for a muscle car and employed an assistant pro who developed the golf cart. Gerald Ford, Bob Hope, Oscar Mayer, Barron Hilton, Ralph Kiner, Joseph Coors, Dean Martin, Perry Como, Hoagy Carmichael, Lucille Ball and Bing Crosby are on past membership rosters.

The Thunderbird model of stylish homes surrounded by manicured green created by founder Johnny Dawson provided a template for the Coachella Valley’s ensuing golf and construction booms. Five other 18-hole courses opened in Coachella Valley during the 1950s. The number continued multiplying until golf construction slowed in the mid-2000s. Who knows what happens if others had not tried emulating what Dawson successfully created at Thunderbird? “I don’t know what would be here if there was no golf,” says superintendent Roger Compton, a Coachella Valley resident since 1979. “There might be agriculture, perhaps using the same amount of water, if not more.”

Thunderbird’s landscape is changing. Compton, in his 25th year as superintendent, stops two dozen times during an 18-hole show-and-tell of the club’s recent water conservation efforts.

Before pausing behind the clubhouse, where his crew replaced 20,000 square feet of maintained turf with desertscape using drip irrigation, Compton reflects on the changes since he arrived in the Coachella Valley in 1979. “The biggest thing and I remember the saying because it came directly from the water district: ‘Water is not an issue. We will never run short on water,’” he says. “We do have a lot of water, but we need to learn to conserve and try to keep that water table from lowering.”

The cost of water in the Coachella Valley has quadrupled in the last 30 years, according to Compton, although courses are still paying less than $150 per acre-foot. Projected increases over the next five years are expected to be among the steepest in the region’s history. Some courses on the California coast pay more than $1,000 per acre-foot. “We can’t complain about the price for water,” Compton says. Still, Compton ekes out savings wherever possible.

Turf between cart paths and walls is being removed. Last summer 1 ½ acres of irrigated turf in an area once supporting citrus trees between multiple front-nine tees was removed and replaced with desertscape. Compton is eyeing similar locations throughout the course for projects this summer. “We want to do some bigger areas,” he says. “If you take an acre out, you are going to save about five acre-feet of water per year. That’s a lot of water.”

A recent summer project involved installing storm capturing capabilities in the wash area. A pump takes the water to a pond that distributes water into an irrigation lake. Compton estimates the pumping captures 10 to 15 acre-feet of storm water per year. “That’s like getting three acres of landscape,” he says. “It’s something we would have never thought of doing 10 years ago.”

Additional water-saving tactics include irrigating overseeded rough three or four times per week instead of daily, reducing non-peak season irrigation and allowing a 10-acre wash area to turn brown in the summer. Compton plans on working with a consultant to reconfigure the irrigation system and he’s mulling installing soil moisture sensors below a few greens, tees and fairways.

“If every course just does a little bit …” he says. “There are always going to be ones that don’t. There’s just nothing you can do about it.”

Explore the March 2017 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Editor’s notebook: Green Start Academy 2024

- USGA focuses on inclusion, sustainability in 2024

- Greens with Envy 65: Carolina on our mind

- Five Iron Golf expands into Minnesota

- Global sports group 54 invests in Turfgrass

- Hawaii's Mauna Kea Golf Course announces reopening

- Georgia GCSA honors superintendent of the year

- Reel Turf Techs: Alex Tessman