Unless you’re feeding yourself or others via playing golf, numbers on a scorecard matter less as you age.

So, I can’t explain why my hands and shoulders trembled. This was supposed to be a lovely fall round on Georgia land Henry Ford once owned. Hit a few shots. Enjoy The Ford Plantation’s incredible turf and scenery. Take dozens of pictures. Conduct a few interviews.

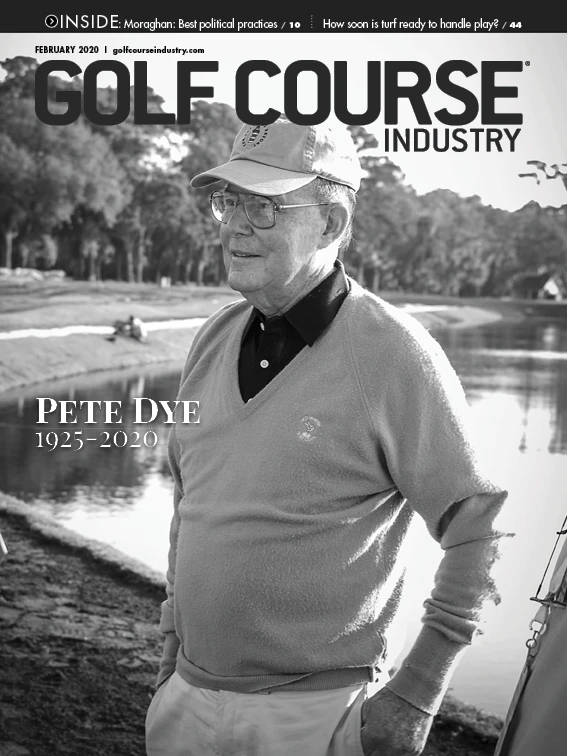

I then saw him, thus the heightened tension. He was munching on an apple, staring into trees adjacent to eighth tee. He noticed our foursome approaching and walked toward the tee. He reached out his hand, “Hi. Pete Dye. Nice to meet you.” I meekly mumbled, “Nice to meet you.”

I wanted to say more. Golf became a serious part of my life in the mid-1990s, when Dye was constructing the boldest and arguably best courses of the era, including Mystic Rock at Nemacolin Woodlands, a public-access puncher 60 miles from my southwestern Pennsylvania hometown. I saw Tiger Woods for the first time and lost dozens of golf balls at Mystic Rock. The boulders, contours, deep bunkers and terrifying shot angles sparked my interest in golf course architecture.

I read “Bury Me in a Pot Bunker” after playing Mystic Rock. I found a copy of George Peper’s “Golf Courses of the PGA Tour” and I intently studied TPC Sawgrass, Harbour Town, Kingsmill Resort and TPC River Highlands, a quartet of Dye designs the pros played.

Just maybe I’d eventually get to meet Dye.

I didn’t have the time to chat with Dye on the eighth tee. We needed to keep play moving. Dye shifted his focus from the apple and trees to our foursome. Even as an 88-year-old in 2014, Dye studied how his products performed. The hole played 162 yards. Firing at the pin required carrying a pond. A miss short, left or right meant trouble. I grabbed a seven iron. Sweat. Swing. Splash! Dye looked at me. He glanced at the pond. “That’s why it’s there,” he said. Everybody in our group chuckled.

A few hours later, I recorded a video interview with Dye. The nerves subsided. I was only six months into an aspirational gig at Golf Course Industry and the most recognizable living golf course architect made me feel comfortable. Flubbing a ball into the water with Dye watching and interviewing him about a cool project capped a memorable trip. I stayed in a cottage with two of Dye’s closest confidants, architect Tim Liddy and construction guru Allan MacCurrach, and USGA Green Section veteran Pat O’Brien. I also met The Ford Plantation’s terrific head agronomist Nelson Caron and a few of his savvy assistants. Replying to a media invitation has numerous perks and long-term benefits.

Spending time with Liddy, MacCurrach and Caron offered clues into how Dye impacted others. We contacted Liddy, MacCurrach, Caron and seven other people who worked with Dye for their perspective for our cover story about the architect’s legacy (page 12). Halting interviews represents one of the hardest parts of the writing process. There’s always another call to make, another document to examine, another anecdote to hear. Deadlines make it impossible to include every angle.Anybody who worked closely with Dye emphasizes he never viewed a golf course as a finished product. His pursuit of greatness didn’t end with a ceremonial tee shot. Deadlines (and finances) made it impossible for Dye to design the perfect golf course.

Magazine profiles are also never complete. People are complex and relationships evolve. Dye’s influence will likely expand posthumously, because he changed the lives of some of the grittiest and smartest people in the golf industry.

I trembled worse while writing this month’s cover story than I did on the eighth tee at The Ford Plantation. You don’t want to flub any assignment, especially one about a subject whose work and humanity affected people from all walks of life, including yourself.

Guy Cipriano

Editor gcipriano@gie.net

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the February 2020 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Advanced Turf Solutions’ Scott Lund expands role

- South Carolina’s Tidewater Golf Club completes renovation project

- SePRO to host webinar on plant growth regulators

- Turfco introduces riding applicator

- From the publisher’s pen: The golf guilt trip

- Bob Farren lands Carolinas GCSA highest honor

- Architect Brian Curley breaks ground on new First Tee venue

- Turfco unveils new fairway topdresser and material handler