I’m a pseudo snowbird. When January arrives, I concoct ways to flee Northeast Ohio. Two of this winter’s trips involved sojourns to Southern California, where I crashed on futons, couches and hotel beds. I visited family and friends, hiked a bunch, ate too much Mexican food, and obtained thousands of frequent-flier miles, rental car bonuses and hotel points. On the first trip, I toured the equivalent of nine 18-hole golf courses in two days.

I also saw rain. It not only rained on the coast. It rained in the desert, creating blooms in scraggly spots. The precipitation altered the PGA Tour’s charge through Southern California, forcing agronomic teams and volunteers to spend more hours pushing water than mowing. Hundreds of crews could relate to what the teams at PGA West, Torrey Pines and Riviera Country Club experienced earlier this year.

Experts are declaring the five-year California drought over. Instead of rejoicing the replenished water tables, lakes and ponds, the golf industry should reflect and prepare to expand its leaner ways.

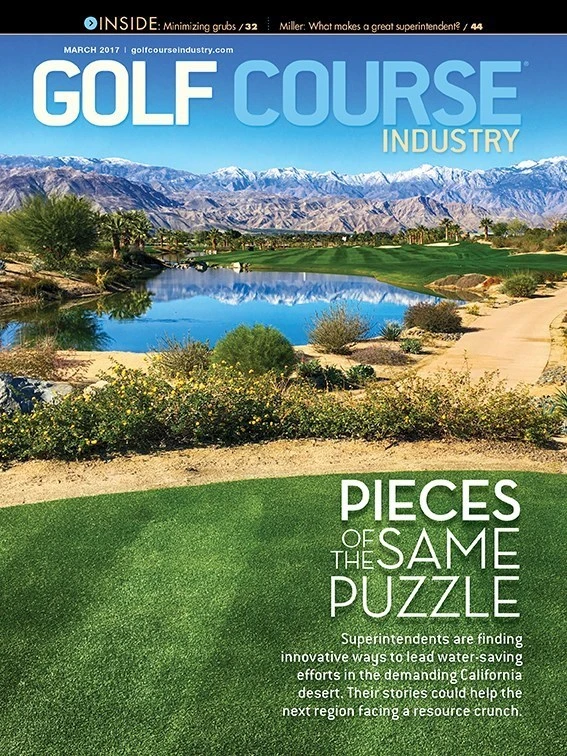

Our cover story, “Pieces of the same puzzle,” explores how proactive superintendents in the golf-rich Coachella Valley are making gradual changes to save water. From a golf standpoint, the changes are overdue. Courses in competing arid markets such as Las Vegas, Phoenix and Tucson operate on less than 100 irrigated acres. Facilities that overseed 130 or more acres are common in the Coachella Valley. That two irrigated acres adjacent to the 13th tee box might be a duffer’s paradise. But they serve no strategic purposes.

Abundant green sells homes – or at least it did during the 1980s and ’90s. Developers used golf course aesthetics as bait, marketing acres of plush ryegrass to northerners looking for soothing winter escapes. Yesterday’s promises place today’s superintendents in tenuous spots. Why take the political risk of altering a property when a few clicks on the irrigation software can provide job security? The absence of enforceable measures and low water costs compared to other parts of California make duplicating ’80s or ’90s aesthetics a safe decision even during a drought.

Precipitation adds a layer of safety. State politicians look outside their Sacramento offices and see rain. The tops of mountains are covered with snow. Media outlets are reporting on floods instead of celebrity drought shamers and “water-guzzling golf courses.” A wet winter has freed the industry from external scrutiny – for now.

“We know there’s a cycle,” says Stu Rowland, the director of golf course operations at Rancho La Quinta Country Club “We know because of our coastal prominence we are going to have significant wet years, but we are also going to have significant dry years. I think the new normal for us is figuring out a way to operate under a model that is sustaining through those anomalous years, whether it’s wetter than normal or whether it’s drier than normal. How can we do this more efficiently without getting into the ‘crisis’ that we were in?”

Shifting landscapes from overhead to drip irrigation, replacing turf in low-play spots, fitting plants to the landscape, extending the gap between irrigation cycles following rain and helping Rancho La Quinta decrease its reliance on groundwater are among the conservation tactics Rowland and his team are pursuing. Ranch La Quinta saved 200 acre-feet of water in 2016, Rowland says, and playing areas are still covered with splendid turf.

The superintendents profiled in our cover story offer a responsible guide on how to prepare for the political effects of a drought while appeasing snowbirds. And don’t think rain will stop snowbirds from visiting Southern California. Have you experienced a Midwest winter?

Explore the March 2017 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Editor’s notebook: Green Start Academy 2024

- USGA focuses on inclusion, sustainability in 2024

- Greens with Envy 65: Carolina on our mind

- Five Iron Golf expands into Minnesota

- Global sports group 54 invests in Turfgrass

- Hawaii's Mauna Kea Golf Course announces reopening

- Georgia GCSA honors superintendent of the year

- Reel Turf Techs: Alex Tessman