The ground roars beneath the abundantly overseeded ryegrass forcing patrons roaming between the first tee and ninth green to stop.

They stop partially because they have nothing else to do on days like Wednesday, April 5, the final hours before 2017 Masters commences. Dangerous storms are imminent, with some reports insisting tornadoes lurk throughout Georgia. Golf champions are spending more time on mobile devices than taking divots from the Augusta National Golf Club turf.

Thousands of patrons must hear the sub-surface roar because a pair of weather-induced course evacuations make passing this spot a necessity on the way to parking lots maintained at fairway height. Whatever is happening and in what amounts beneath the ground will never be fully revealed. The ninth green is 50 yards away, and the small number of patrons with an inkling of the sound’s significance are mesmerized. One man drops to a knee and takes multiple pictures of the catch basin, an entryway to the Augusta National underworld. He listens carefully. He’s sure to have heard birds chirp while watching televised coverage of the 13th hole. But he’s never heard a sound like this on a golf course.

He scurries after taking the pictures. There’s plenty to see inside the gates and below the omnipresent trees. And there’s not a lot of time to see it.

Everything about a day like Wednesday should be frustrating. Bad traffic. Rollercoaster-length lines to enter a gift shop. Enough time to consume perhaps 20 ounces of beer or sweet tea before being told to evacuate again. Not possessing a mobile device as a serious weather event approaches. No extended Dustin Johnson, Rory McIlroy, Jordan Spieth, Jason Day, or for that matter, Rod Pampling sightings.

Somehow everybody remains docile, because they hear noises like the roar between one and nine, and see with their own eyes what they have watched on a screen for decades. The short time inside the gates demonstrates topography and undulations television can’t possibly depict. Walking the 11th and 10th holes from green to tee makes missing a morning workout tolerable and justifies devouring modestly priced, carb-heavy offerings.

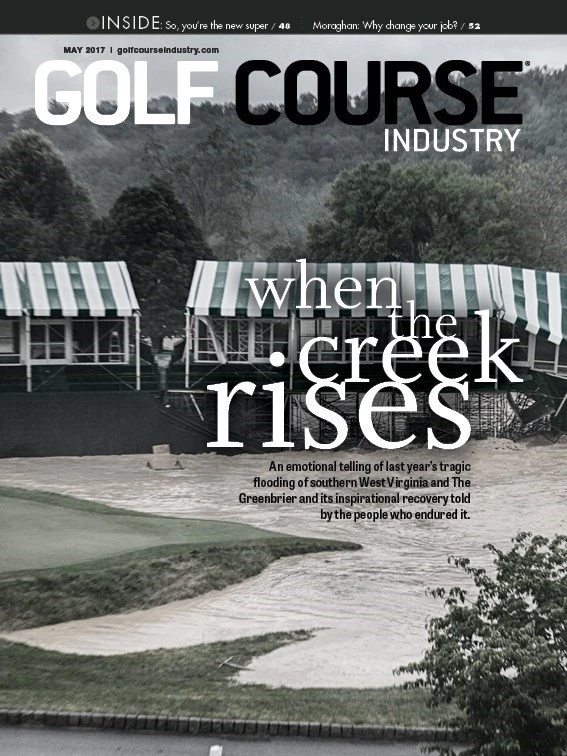

The Masters flourishes because it boasts golf’s biggest star: the 18 most familiar and mysterious holes in the world. Even people who don’t know a wedge from a fairway wood reserve early April for dogwoods, azaleas, pine trees, slick bentgrass and a spot announcers call Amen Corner. Ask more Americans if they know Rae’s Creek or Antietam Creek. One intersects a playground; the other intersects where the bloodiest hours on American soil occurred.

Only a few know how the turf surrounding Rae’s Creek remains stable and vibrant. Deep, clean bunkers and ornamental blooms are less appetizing if erosion exists. Had the land Augusta National occupies remained a nursery or turned into residential development, Rae’s Creek would be just another teetering body of water. Inside the gates, it produces interpretative moments. Everybody who watches the Masters feels something when they see the creek.

Golf course superintendents interpret Augusta National in dozens of ways. Enthralling to some, an unrealistic measuring stick to others. Customers also experience interpretative moments. This marks the 50th anniversary of the first Masters broadcast in color. “From that April to this, golf course superintendents all over the U.S. came to dread the Monday after the Masters,” author Curt Sampson writes in “The Masters.”

A resident living in a cold-weather city says the Masters energized him to purchase his first color television. Stories like his are duplicated by younger generations who used the Masters as an excuse to purchase a HD television. Name one golfer who forced consumers to change the technology in their homes? Tactfully tempering expectations has become one of the most important parts of a superintendent’s job because of the Masters.

Communicating why no other golf course can look and play like Augusta National should be a lesson in every turf school. But teaching “Masters Maintenance” would be akin to leading a folklore or mythology lecture. The club guards its secrets, so the few employees who know the exact science behind the course remain quiet.

Preserving golf’s biggest star requires immense human and financial resources. The people responsible for this act make subtle appearances on days like Wednesday. A pair of utility vehicles stop below the sixth and behind the 16th green as patrons evacuate the course. Three men emerge from the vehicles, flip the beds and hoist weighted bags on their shoulders. Patrons clutch their cameras and take pictures from multiple angles. Some ask the workers if they need help. The men say little. They place the bags in a semi-circle behind a catch basin in a low-lying area. They are neither rude nor revealing.

On a day when many admirers never witnessed a golf shot, they endured nasty weather to sneak a few glimpses of a golf course. Nobody wanted to leave.

Tartan Talks No. 10

Bill Amick has implemented and shared a few ideas throughout his career.

Amick, who started his own golf course architecture practice in 1959, joined “Tartan Talks” to describe ways to integrate options for learners into existing courses. And here’s the zaniest part of Amick’s concept – it involves no putting. “It’s the most delaying part of the game,” he says.

Seven decades in the business isn’t delaying Amick from seeking work in new places. His current project is a collaborative effort with fellow ASGCA member Mike Beebe in the South Pacific island of Tongoa. Enter bit.ly/2nW6PaN into your web browser to learn more about golf without putting and designing a golf course in Tongoa.

Explore the May 2017 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show