Last month, I wrote about the historical background of how trees became such fixtures on American golf courses. But there’s much more to say.

I’m in favor of removing of trees where necessary, but the trick is figuring out which trees must be removed, which often causes disagreements. A golf course superintendent might want a tree removed for agronomic reasons. But if he removes a tree, members of the club might treat the loss of that tree like a death in the family.

In this sensitive area, superintendents generally prefer an honest dialogue, even if a decision goes against their wishes. Only in rare circumstances would one emulate the superintendent who names his chain saw lightning so he could “honestly” tell members that lightning took down the tree. Other superintendents have staged occasional “construction accidents,” often using employees who were leaving anyway as scapegoats. And some architects have made math “errors” on master plans, removing 243 trees instead of 143.

My favorite tree-removal story is the superintendent who was ordered to “save” a large tree. He later professed innocent confusion about the members’ intent after stacking the logs neatly in the clubhouse fireplace.

I’m not recommending superintendents do any of this. It takes sales skill to demonstrate the benefits of removing long-loved trees. Typical common-sense approaches might include detailing the resources a superintendent would expend to resod, rope or spray areas that are too shady to grow turf – expenses that appeal to members’ pocketbooks. A superintendent might demonstrate that other trees have been removed without ill effect. Few members could pass a test of where trees have been removed, assuming there are plenty left for backdrop or a superintendent didn’t take one out where a member buried his dog years ago.

Superintendents might feel more comfortable making a potentially political decision with the help of an independent expert. I’ve been called in to consult on only one tree. Playability, aesthetics and safety are considered when making a decision to keep or remove a tree. Relieving straight-line planting and recovering long-lost views are two good reasons to remove a few trees.

Playability issues

The surest way for a superintendent to receive permission to cut down a tree is when he can claim it blocks a shot from the fairway or if it’s a double hazard that blocks a direct shot at the green from a fairway bunker.

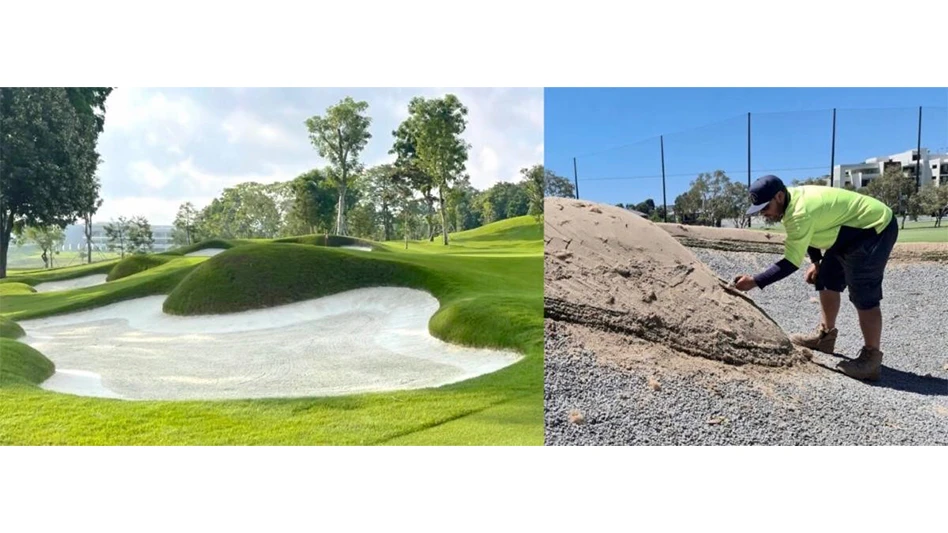

As a result, we deem architecture that requires the need to clear a bunker lip and stay under or go around a tree as a double hazard, and thus, unfair. Trees beyond bunkers is the most common example of the double-hazard concept, but some argue that any high lip on a fairway bunker or anything less than a firm, perfect bunker lie also is an unfair double hazard.

A smaller and diminishing minority of old-school players believe shots that are equally easy from the short grass or fairway bunker diminish the shot value of the hazard.

I generally agree with the premise that a good-to-spectacular recovery shot from a sand bunker makes for exciting golf. I like the concept of a half-stroke penalty (meaning, on average, a recovery shot will find the green about half the time, not that one could end up with a score of 4.5). So I usually design fairway bunkers with shallow depth and gentle slopes that allow this to happen. Allowing forward play is practical to ease maintenance and speed up play.

Golfers accept many of these hazards as part of the game. However, they might complain about a tree that has grown across the fairway far enough to block a clear shot to the green. At one club, I was called in for a discussion about whether it’s fair to be blocked from going for the green from any point in the fairway. In that case, the tree should be removed further toward the rough, given the large number of players it affected and because it was a short par-4.

I often save specimen trees just beyond normal landing areas to affect strategy. At Cowboys Golf Club near Dallas, there’s a specimen tree about 350 yards off the tee on the 12th hole that’s trimmed high because it can block the green from the far left of the fairway. A big hook or low-running shot is required to reach the open front green. Golfers learn the right side is preferred. And while golfers have an option to get to the green from the left, they must invent a shot. This creates the half-shot penalty.

I like not providing golfers road signs on every hole, telling them exactly what to avoid. Why is a low-running or big-curving shot less exciting than a recovery shot from a bunker when it’s successfully pulled off?

I also like an occasional tree encroaching into the fairway to force a draw or fade from the tee. I’m always careful to leave enough room to find some part of the fairway with other shot patterns. These work best at about 180 to 210 yards from the tee because the ball reaches its vertical apex and maximum horizontal curve there.

Sometimes trees located close to tees make for better safety, but placing them too close to the landing areas creates another lateral hazard.

Equal consideration

There are many perspectives to consider when trying to reverse the long-term results of continuous tree planting. A course’s or club’s consulting architect should help superintendents determine which trees should be saved or removed. Playability, safety and aesthetic aspects of any hole should be considered equally with a superintendent’s agronomic needs.

Trees are beautiful and necessary on most golf courses and deserve careful consideration. Now I’ve put a lot of brain power into making decisions to remove trees, so pass the aspirin, and let’s go look at the next tree. GCN

Jeffrey D. Brauer is a licensed golf course architect and president of Golfscapes, a golf course design firm in Arlington, Texas. Brauer, a past president of the American Society of Golf Course Architects, can be reached at jeff@jeffreydbrauer.com.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the March 2005 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Toro continues support of National Mayor’s Challenge for Water Conservation

- A different kind of long distance

- Golf Construction Conversations: Stephen Hope

- EnP welcomes new sales manager

- DLF opening centers in Oregon, Ontario

- Buffalo Turbine unveils battery-powered debris blower

- Beyond the Page 66: Keep looking up

- SePRO hires new technical specialist