Not many golf course superintendents move from a course with cool-season turfgrass to warm-season turfgrass. And still fewer superintendents move from courses with warm-season turf to cool-season turf. But those who do are dispelling the myth that it’s too difficult.

“People are reluctant to move from South to North and North to South because there’s a misnomer that if you’ve never grown cool- or warm-season grass, then you can’t,” says Jim Hengel, director of grounds at the 18-hole Miromar Lakes (Fla.) Beach and Golf Club. “But if you adhere to good agronomic practices such as aerification, water management, topdressing and fertilization, you can be successful. You need to be actively involved with the golf course. You can’t sit in your office, or ride by in a cart. You need to get out and feel the grass.”

Making the move

Hengel has been at Miromar Lakes since June 2005. He came from the Links at Hiawatha Landing in Apalachin, N.Y., where he spent 12 years. During his last year at Hiawatha, Hengel also managed Traditions at the Glen in Johnson City, N.Y. He was the director of operations at both courses simultaneously and part of an ownership group. Hengel says he moved because it was a lifestyle decision.

“My kids had graduated from college, and my wife and I wanted to move south because we were tired of the winter,” he says.

When Hengel interviewed at Miromar, he was asked about his lack of warm-season turfgrass experience, but that didn’t prevent him from getting the job.

“I sought out endorsements from the likes of [consulting agronomist] Terry Buchen and other friends who came from the Northern climate to dispel the rumors [that I couldn’t manage warm-season turf],” he says. “Initially, there was concern, but I pointed to other people I knew who moved down who had little trouble adapting. So much of it is management.”

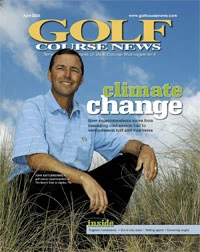

John Katterheinrich, golf course superintendent at The Bear’s Club in Jupiter, Fla., has moved south, north and then south again. After Katterheinrich graduated from The Ohio State University in 1980, he moved to Florida to work at Lost Tree Club in North Palm Beach, near Jack Nicklaus’ home. Katterheinrich got to know Nicklaus, who was a member there. Katterheinrich worked at Lost Tree from 1980 to 1990, then worked at Interlachen Country Club in Edina, Minn., from 1990 to 2001.

“I was born in Minneapolis, and my brother lived there,” he says. “My buddy was a green chairman at Interlachen, and that’s how I found out about the job.

“I’m a 10-year guy,” he adds. “I was challenged moving up to Interlachen. I went up there three times. They liked me but were concerned about me making the transition. I attribute how well I made the change to a great assistant who helped me relearn the things I had forgotten. It seems nowadays the resources are so much more – other superintendents, vendors, etc. – people are so helpful, which made for a smooth transition.”

Another reason why the change wasn’t that difficult for Katterheinrich was because the superintendent before him had excellent records that went back 10 years, the course was in good condition and the assistant had a plant pathology degree.

“My concern was disease pressure and control because you don’t get as much pathological disease in the South,” he says. “Cutting heights and mowing weren’t a concern.”

While at Interlachen, Katterheinrich went to Florida on vacation and ran into Nicklaus, who told him about The Bear’s Club, which he designed and owns.

“I came out to see The Bear’s Club because it was brand new, and I knew the golf pro,” he says. “The course had a couple of problems, and Jack was in the process of making a change. Jack had all the confidence in me, and I had confidence, but the job wasn’t as easy as I thought. TifEagle was a newer grass at the time, and it took me a little time to get back to where I was when I was at Lost Tree. I had to relearn some things.”

Although not as challenging as Hengel’s or Katterheinrich’s moves, Bob Randquist, CGCS, shifted from the transition zone to the South. Randquist has been the golf course superintendent at Boca Rio Golf Club in Bacon Raton, Fla., for seven and a half years. Before that, he worked at Southern Hills Country Club in Tulsa, Okla., for 19 years. He went from managing bentgrass greens to Bermudagrass greens. However, Southern Hills had Bermudagrass fairways and rough.

Randquist and his wife had talked about moving to a warmer climate, then he was contacted by an executive search committee and ended up at Boca Rio. When interviewing for the job, Randquist had a brief discussion about his comfort level with Bermudagrass. During his first year at Boca Rio, the greens were regrassed with TifEagle.

“It was pretty new at the time – only a few other courses had it,” he says. “It’s a much shorter-rooted grass. It behaves more like a bentgrass, and needs more hand-watering. I verticut frequently but not as aggressively.”

Randquist went from 35,000 rounds a year on a 27-hole course to 12,000 rounds a year on 18 holes. There are 150 members at Boca Rio compared to 600 stockholders at Southern Hills. To soften his transition, Randquist attended Golf Course Superintendents Association of America chapter meetings when he arrived in Florida.

“I got to know other superintendents and asked them about the nitrogen applications, aerification and verticutting to help formulate my program,” he says.

North/South difference

To get up to speed on warm-season turfgrass, Hengel attended GCSAA seminars about root zones, warm-season turfgrass management and ultradwarf Bermudagrass. He also did a lot of homework.

“The biggest challenge for me is that I came from a different cultural background,” he says. “This is the first time I’ve worked with Hispanics. There’s also the 12-month growing season, although summer play is light, and we do aerify more often than we did in the North. I had to throw away the calendar I was used to because all cultural practices are done during what is prime time in the North.”

Another challenge Hengel deals with in the South are torrential rains and coring, which is done the summer to remove organic matter.

“Up north, organic matter accumulates, but it stops or slows during the winter,” he says. “Down here, you need to be more aggressive with aerification.”

pressure also is a whole different regimen in the South. There’s more disease and destruction in the North, however, there are more nematodes in the South, Hengel says. The insect cycles are more predictable in the North than in the South, and weed problems are a bigger problem in the South because there are more grassy weeds and broadleaf weed problems.

“You can time things better in the North,” he says. “I’m still learning the cycles down here.”

In the North, Hengel says people jam a lot in a short period of time, then relax.

“You need personal time management skills to get time for yourself,” he says about working in the South. “Right now, I have a 12-day-on-and-two-day-off schedule. I have every other weekend off. You can’t do that in the North. This becomes more of a routine in the South because the weather is so consistently good and the urgency to get a project done in a short time isn’t there.”

One thing Hengel didn’t expect to do much of was overseed. But he’s been managing ryegrass in the fairways and rough, so coming from the North is an advantage.

For Katterheinrich, organic matter and thatch were challenging because Bermudagrass is aggressive.

“I got here when the course was a year and half old, and it had a lot of organic matter build-up,” he says.

“Golf expectations changed a lot since the last time I was down here,” he adds. “Jack’s always looking for grain in Bermudagrass greens. I had to work hard to minimize it, but you can’t eliminate it.”

One big difference Katterheinrich sees is that warm-season grass is more durable.

“With cool-season grass, it seems like you’re tip-toeing a bit more,” he says. “If you get behind in the North, you can lose a season quickly because the grass is less aggressive and the season is shorter. You can get yourself out a problem quicker down South because of the temperatures and the more aggressive turf.”

A difference that stands out for Randquist is mowing year round in Florida because of overseeding. Because of that, the equipment never get a rest. Also Randquist tended to undertake projects during the winter in Oklahoma but was limited because of the frozen ground. In Florida, there’s a much higher ability to be productive in the off-season because the weather allows it.

“In Oklahoma, I had to rely on seasonal labor,” he says. “I’d cut the crew down in the winter and was always training new employees every season. Here in Florida, I use the same maintenance crew year round so we don’t spend a lot of money hiring and training new employees.”

Randquist also deals with different insects – such as mole crickets and fire ants – and weeds in Florida compared to Oklahoma. But he has garnered information from other superintendents and developed programs based on what they do.

Due diligence

For those thinking about making such a move, Hengel suggests conducting research, taking seminars, talking to superintendents in the areas where one wants to relocate and talking to people who travel a lot. He says a move from South to North or vice versa definitely enlarges one’s resume and opens up more opportunities.

The biggest thing to do when thinking about such a career move is to reach out and talk to other people and prepare oneself, Katterheinrich says.

“I talked turf to a lot of guys up North before I went to Interlachen,” he says. “Just learn and try to pick up different practices. The more people you talk to the better you are.” GCN

Explore the April 2006 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Conscientious of a bigger role

- Bernhard and Company partners with Laguna Golf Phuket

- Terre Blanche showcases environmental stewardship

- VIDEO: Introducing our December issue

- Bernhard and Company introduces Soil Scout

- Nu-Pipe donates to GCSAA Foundation’s Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA enhances golf course BMP tool

- Melrose leadership programs sending 18 to 2026 GCSAA Conference and Trade Show